Florida’s high school seniors face higher graduation bar with fewer ways to make it

The Palm Beach Post | By Sonja Isger | July 6, 2021

Ten days after the 2021 school year ended, Palm Beach County high schools came buzzing back to life this week as thousands of students returned to make up lost ground.

For the soon-to-be seniors in the group, the need is urgent and the obstacles to graduation greater than for any class that came before.

Nearly 5,800 students in the class of 14,000 still need to pass one or both tests required by the state for graduation — a number almost double what was seen pre-pandemic, according to the district’s data.

And because of changes imposed on the Class of 2022 years ago, circumventing those test requirements by using alternative scores from other state or national exams will be harder, as the state has hiked the necessary minimum scores and changed the test options.

n the past, more than a third of the county’s graduating class has secured a diploma using these “concordant scores” on other tests including the ACT or SAT.

Next year’s seniors were sophomores when COVID-19 scuttled their first shot at passing the statewide exams and also limited for the next year their options to retake them or sit for the alternatives.

Meanwhile, the county’s high schoolers were more likely than their younger counterparts to sit out the pandemic at home, with 62% still learning remotely in April, compared with 24% of elementary students and 47% of middle schoolers, the district reports

“It’s a higher bar with less opportunities to get ready for it. It’s a double whammy,” said FairTest Executive Director Bob Schaeffer. “And whatever you think of graduation tests, it’s not fair, not for the class of 2022, maybe even 2023. They all lost a year-ish of regular school.”

Florida was among 11 states that required tests for graduation

Pre-pandemic, Florida was one of only 11 states where statewide tests hold the key to graduation, according to FairTest’s national inventory. Those tests were the Florida Standards Assessment in English language arts (reading and writing) and the Algebra 1 end-of-course exam.

The state allowed for scores on other tests to be substituted, but in 2018 Florida’s Board of Education worried the bar was too low, giving students a false sense of accomplishment and failing to prepare them for college-level work.

While a growing number of states, including Georgia and California, ended their testing, Florida moved in the other direction, requiring higher scores.

In a simulation run at The Palm Beach Post’s request, if the senior class of 2019 had been held to the new, higher standards, the district’s 87% graduation rate, including charter school students, would fall 17 percentage points to 70%, reported Adam Miller, assistant superintendent for performance and accountability.

“Among those graduates who would not have received a diploma: 44% are Black, 38% are Hispanic, and 26% are English-language learners,” Miller said.

Schools have been getting ready for the graduation changes

Fortunately, the change has been years in the making, and school leaders have used the time to employ various strategies to lift students.

Multiple principals reported doubling up on math courses so that a student weak in Algebra 1 is simultaneously enrolled in a “liberal arts” math class that gives them additional exposure to the subject’s underpinnings.

In math, the state took away a preferred algebra exam alternative, the PERT, a placement tool given to Florida’s incoming freshmen. On the upside, when the state was unable to administer the spring 2020 exams in algebra, it amended the math graduation requirement to allow students to check the box by passing the geometry end-of-course exam.

Principals report beefing up their intensive reading instruction as well both during and after school.

But it is clear that the district expects alternatives to the state’s exams to play a significant role in getting students across the finish line.

Of the $8 million in federal COVID relief money it will spend in high schools, the district intends to spend $1.5 million to bring in 21 teachers to 12 of the district’s most disadvantaged schools to address the matter of concordant scores, GPA and credits needed for graduation, according to a budget presentation last month.

“We want to make sure we give the students every opportunity to meet this requirement,” said Keith Oswald, the district’s chief of equity.

Students will need to score 50 more points than their predecessors on the SAT reading and writing test. The SAT reading subtest alone is no longer enough. On the ACT, they must now average both the English and reading subtests and get a score of 18 or better rather than rely on the reading score alone.

While students can use a passing geometry EOC, they can no longer use the PERT if they fail the Algebra 1 exam. They can also take the PSAT/NMSQT in math, the SAT math or ACT math.

At Palm Beach Lakes High, SAT/ACT boot camp begins next week, timed to come within two weeks of the next ACT testing date. Even before the federal money came its way, the school had used other grants to tackle SAT test prep and also to cover the cost of additional exams. (Every high school student in the district gets at least one free sitting.)

The priority placed on these tests is evident in the opportunities Palm Beach Lakes and the district provide to prepare and take the tests.

Both SAT and ACT give two free tests to any students nationally who receive free or discounted lunch. More than 90% of Palm Beach Lakes students get those benefits. Also, the district pays for an ACT during the school day test in the fall for any senior who needs concordance district-wide.

The district also pays for all juniors in the county to take the SAT test during school in March. It also pays for seniors who need concordance to take that test.

At Palm Beach Lakes, the School Advisory Council uses some of its discretionary money to pay for SAT and ACT tests for students who run out of waivers.

‘Money is not a barrier’

“Increasing graduation rates is a main school improvement goal at Lakes,” Principal David Alfonso said. “At Lakes — money is not a barrier to getting a concordance score from SAT or ACT.”

“My students are lucky enough they receive waivers for those tests — four waivers,” Alfonso said. “A lot of times those tests get pricey.”

Without any statewide test scores from spring of 2020 and last spring’s scores still being calculated, Alfonso and his fellow principals are focusing on what can get done now.

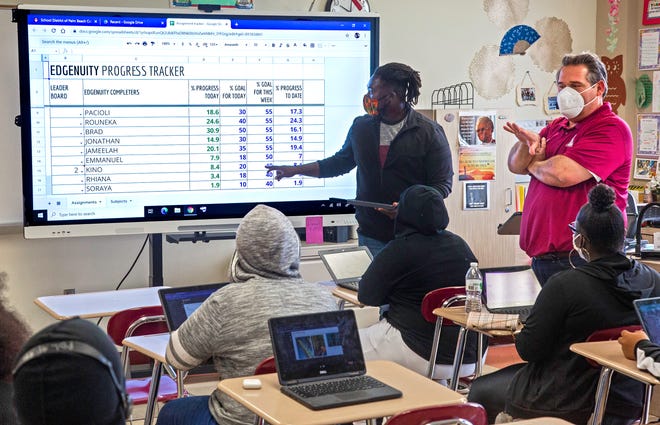

This week, 412 students of 500 invited were at Palm Beach Lakes taking other steps toward graduation, specifically making up courses in which they previously were awarded D’s or F’s.

Laura Yuan’s class is a sea of 22 students working with masks on at desks, laptops open, each working at his or her own pace in courses including U.S. history, English and science.

Omarion Metayer, a junior in the fall, is trying to raise a D he earned in English 2. “It’s better than virtual actually,” he says of summer school. He says he had a tough time “waking up early just to hop online” last year. And the D — it’s the one blemish on his otherwise all-A-and-B transcript.

A couple seats over, soon-to-be senior Erlin Ortiz is retaking the physical science class she didn’t pass in her freshman year, when she didn’t realize every credit counts. Last year was a wash, she said.

“In quarantine, I was lazy. Here, I focus more on my work,” Ortiz said.

Alfonso doesn’t want credit going out on these online credit recovery course for any scores less than 80% and he’s asking that students pace themselves to get through 10% of the coursework a day. Summer school is only four weeks long — and most weeks stretch only four days.

Forest Hill High is also seeing record summer school turnout, said Principal Esther Rivera.

“It hasn’t been just the score change our students had to deal with,” Rivera said. “A lot of my students took fulltime jobs or became fulltime babysitters for their brothers and sisters during the pandemic.

“They were in survival mode,” said Rivera, who knocked on doors and tracked students through their social media accounts to pressure them to show up for summer school. She insisted on getting student cellphone numbers, knowing that if a student didn’t show, calling a parent at work might not pay off.

The school has a team tracking students at risk of not graduating, and the credits and test scores they need to get there. She is hopeful that they will get there despite the raised bar.

Principals have seen the pattern before.

“If you set the bar higher, the students will get there,” Rivera said.