A new kind of charter school just launched in Hillsborough. A look inside.

With two area campuses and another on the way, the IDEA charter group is giving traditional public schools a run for their money.

Tampa Bay Times | By Marlene Sokol | November 16, 2021

Katina Grace wanted more for her daughter than what she herself remembered as a child in school.

By Grace’s description, the Hillsborough County public schools never really pushed her to excel. She could not recall many personal connections with teachers or staff. “I had to push my own self,” said Grace, who now works as a junior chef.

Grace liked what she read about IDEA Public Schools, the charter organization that launched two schools this year in Hillsborough County. She was impressed with their emphasis on college preparation, their promises of individual attention, and the fact that they advertised for business.

For 6-year-old Aaliyah, who loved math and had preschool teachers singing her praises, it seemed like a safe bet when she was ready to enter kindergarten.

“They don’t play with education,” Grace said.

The IDEA schools, which were fast-tracked for state approval under the new “Schools of Hope” system fashioned by education commissioner Richard Corcoran, exist to give students an escape from neighborhood schools with a history of poor performance.

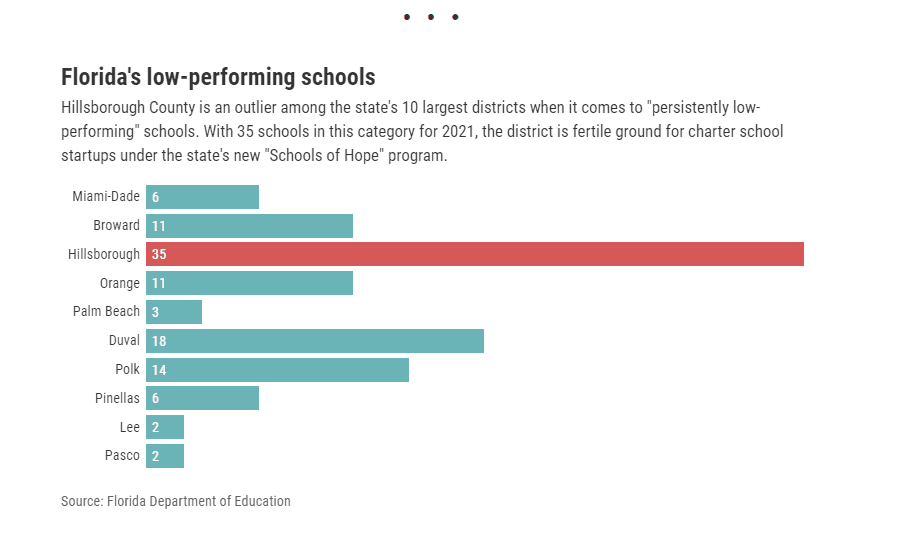

Hillsborough has 35 such schools on a state list, giving schools of hope a clearer shot in that county than anywhere else.

But can the IDEA schools live up to their advertising claims, which suggest virtually every student will one day go to college? Can they replicate the results they achieved in Texas, where critics accuse them of skimming off the strongest students and depleting the remaining schools of needed resources?

And what is the cost in Hillsborough if they succeed?

Working out of brand new buildings in urban shopping strips, one on Fowler Avenue and the other east of Ybor City, IDEA is educating about 900 students in its inaugural year, more than half from neighborhoods served by D and F public schools.

And that’s with only grades K, 1, 2 and 6 in operation.

When complete, these K-12 schools will be able to accommodate nearly 3,000 students. A third school, opening next year in the Thonotasassa area, will take that total past 4,000. There are plans for a fourth in 2023, just over the Polk County line, which might have room for some Plant City students.

And IDEA is not likely to be the only provider. Mater Academies, another state-approved organization, secured approval this year for two conventional charter schools in eastern Hillsborough.

IDEA did not arrive without controversy. Stung by reports of lavish executive spending and a management shake-up in Texas, the nonprofit organization got a cold reception from some members of the Hillsborough School Board, who see charters and private school vouchers sapping $300 million a year from their budget.

Critics, led by board member Nadia Combs, assumed IDEA would not provide student transportation, a deal-breaker for many low-income families. They were wrong. Yellow buses arrive every morning.

Breakfast and lunch are free, with a state application pending to offer free supper as well, said Tampa Bay executive director Julene Robinson. After-school care is also free, for now, thanks to IDEA’s creative use of federal COVID-19 relief funds.

But for parents who have enrolled their children, the biggest draw is the school’s relentless focus on strong academics and college preparation.

“Their curriculum is different from public schools,” said Zhamagne Obsid, a recent immigrant from the Philippines who has one child in second grade at IDEA and the other in fifth grade at the district’s Pizzo K-8. “There is more science, language and math.”

While not dissatisfied with Pizzo, Obsid said she looks forward to having both children at IDEA next year.• • •

The Fowler school is called IDEA Victory — sometimes “Victory Vinik” in honor of Jeff Vinik, the developer and Tampa Bay Lightning owner who extended a charitable commitment of $5 million.

During a recent visit, school leaders led a reporter on a tour that included several classes, the cafeteria and common areas, and a mid-morning change of classes.

Divided into five groups, the 143 sixth-graders crisscrossed the hallway in almost military formation, eyes ahead and masks up to protect against COVID-19. They get five minutes to get to their next class, said Kendrah Underwood, principal of the upper school. They aim for under three, and Underwood has clocked them at closer to two.

“It shows everything is running like clockwork, and we are maximizing the learning time,” Underwood said. “It also shows our scholars care.”

Classes were tightly structured with teachers asking students frequently to repeat a vocabulary word that flashed in red on a smart board, or signal that they understood a concept.

“I need your hands free, eyes on me,” English language arts teacher Monique Henry told one group. “Tilt those (computer) screens 45 degrees. Hands free, eyes on me. Waiting for 100 percent.”

She directed them to read the term, “figurative language.”

“What do we know about figurative language?” she asked. They read from a passage that included the phrase, “ear-splitting music.” She stopped. “Are her ears literally splitting? No. How do you know they are not splitting?”

Another class was close-captioned in Spanish, with lines of type moving across the board, as an aide for students who still are mastering English.

They are, in many cases, playing catch-up in their basic skills.

Consider Miles Elementary, the north Tampa school whose neighborhood sends the greatest number of students to IDEA, 51. Eighty-one percent of Miles’ third- to fifth-graders scored below grade level when state reading tests were last administered in spring. Sixty-one percent were at the lowest of five levels, indicating they are “highly likely to need substantial support.”

Forty-three students are from Shaw Elementary’s attendance area, and 41 from Robles Elementary. At both those schools, the below-level reading rate stands at 86 percent and the Level 1 rates were 63 and 66 percent.

Those numbers are not an accident, said vice president Adam Miller, who worked for the Florida Department of Education before joining IDEA. As part of its agreement with the state and school district, IDEA recruited most intently in the neighborhoods served by Hillsborough’s lowest-performing schools.

The testing data allows the IDEA teachers to drill down to specific skills, such as vocabulary, and design their lessons with those gaps in mind. Students and teachers can measure real-time skill mastery on a variety of computer platforms, which parents can monitor from home. They also are able to text the teachers on these platforms, a feature Katina Grace uses frequently.

The students are divided into cohorts — known as “houses” in some district schools — to create both camaraderie and competition. Some schools name the houses for character traits such as “honesty” and “integrity.”

At IDEA, they are named for colleges of various types: University of South Florida, Hillsborough Community College, Erwin Technical, Saint Leo University and, in a nod to the local demographics — 60 percent of IDEA’s Hillsborough students are Black — Bethune Cookman University.

The strong emphasis on college is a prevailing theme throughout the organization, which was founded in 1998 by educators from the Teach for America movement. In its promotional pieces, IDEA advertises 100 percent college acceptance for its graduates, a pitch that appeals to many parents.

Critics say that pitch is misleading because, as IDEA’s Texas handbooks explain, graduation requirements from an IDEA school include acceptance into college.

And not all students make it all the way from 9th to 12th grade. Some are asked to repeat a grade if they do not pass their state tests, and they revert to district schools as a result. A 2011 study by education scholar Ed Fuller, funded in part by the Texas teachers’ union, showed only about 65 percent of students stayed the entire four years.

Miller said the IDEA organization was able to demonstrate to its critics that its rate of student loss in Texas was about on par with regular public schools in the surrounding communities. He said promotion decisions in Florida will be made on a case-by-case basis, balancing the need to make sure students have mastered the material with a desire to be compatible with the district school system.

As for the promise of college: The Florida handbook does not specify college acceptance as a requirement for graduation. But Robinson did not rule out that possibility as the schools approach their first graduation year, 2028. She said school time will be devoted to preparing students for college and taking them step-by-step through the application process, even if some ultimately decide not to go.

“We do our part in partnership with families to know that they have a path forward in higher education,” she said.• • •

During a second visit to the Fowler campus, more than half the students still were on site in the after-school hours. There was homework help in the cafeteria before the children were ushered in groups to enrichment activities — on this day, art projects, science experiments and outdoor soccer practice.

Underwood introduced the reporter to sixth-grader Brooke Grant, the daughter of an aspiring IDEA principal.

“It feels like they really want to prepare me for college,” Brooke said of the school.

She said she enjoys her English class. “I feel like with (English language arts) I can learn how to express myself in my writing,” she said. She likes her culinary elective and wants to pursue cosmetology as a career, but her mother is steering her toward law.

Tykhari Knight, who entered IDEA after completing fifth grade at north Tampa’s Witter Elementary, was more tentative in her remarks. She said she finds the work at IDEA challenging. “I’m not really good with reading,” she said. But, she added, “I feel like I’m improving a lot.”

Underwood said she is working with Tykhari to “try and help her find her voice.”

Unlike conventional schools, which use district-hired teachers for electives throughout the day, IDEA saves music, art and other non-academic classes for the afterschool program in elementary school.

That way, the students can spend more day hours on academic enrichment programs such as accelerated reading and “Hotspot,” a computer-based math program. And, Robinson added, the teachers can collaborate as they adjust to a community and student body that are completely new.

A local nonprofit organization called G-3 staffs the after-school classes. G-3 also teaches middle school electives during the school day, in a kind of outsourcing that would not happen in a district school.

Culturally relevant reading materials are embraced at IDEA, where a library now under construction displays biographies of former U.S. President Barack Obama and Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

There are lessons in mindfulness from Marco Mooyoung, a specialist whose position is funded, in part, by a grant. Mooyoung gets involved if a student is out of sorts, perhaps due to stress at home, or a conflict with another student. He might let the student shoot baskets in the gym, or ride one of several small exercise bikes to let off steam.

“I won’t lead the conversation,” Mooyoung said. “I’ll tell them, ‘What do you want to talk about?’ And I’ll tell them, ‘What can I do to help you fix this?’ And they’ll actually give me advice. It creates an environment where they advocate for themselves.”

Many of the innovative practices at IDEA can be found at district schools as well.

McLane Middle School in Brandon introduced meditation about five years ago, after spending a decade with the district’s highest number of expulsion cases. Mort Elementary, Potter Elementary and other schools employ the house system to encourage common goals. And culturally relevant reading materials can be seen increasingly in district schools.

At Lakewood Elementary in Pinellas County, test scores improved dramatically after the students were encouraged to “own” their data. And in east Hillsborough, Kenly Elementary improved from a D to a B with a hyper focus on individual student data that the district is now trying to make standard in the schools that comprise its Transformation Network.

In the IDEA schools, these strategies already are standard practice, and school leaders say they want to go further. Plans are in the works at the Fowler campus to offer child care and mindfulness instruction as early as 6:15 a.m. It’s something the community wanted, Robinson said.• • •

Combs, the school board member, said she had not yet visited the IDEA schools. But she remains skeptical.

She wonders what the schools’ long-term prospects are. Early on, charter schools receive a wealth of start-up grants from the state and federal government, and she wonders if the schools will deteriorate when that money stops flowing. Miller said IDEA plans for these funding fluctuations in its budgets, assuming that enrollment growth will translate into more per-pupil payments from the state as the grants wind down.

Combs said she disapproves of limiting music and art instruction during the school day. “I personally think that is very difficult for a child,” she said. “Kids need something to look forward to, something to use their creative minds.”

Robinson acknowledged the rigorous school day. “Every minute matters if we are going to deliver on our promise to families,” she said.

Balance, she said, comes from drumline sessions, after-school soccer, dressing up for Spirit Week and faculty-student kickball games in what she called “the intentionality around joy.”• • •

Aaliyah Grace’s time at IDEA Victory has not been without some hiccups.

Early in the school year, her mother said, she came home, upset about a racial epithet that a classmate had used to address her. Katina Grace was furious. She did not even realize her daughter was familiar with the word, and she wondered about the influences among IDEA’s students. “She was learning things that she didn’t need to learn,” she said.

But Grace said school leaders handled the incident responsibly. And Aaliyah is now friends with the other child.

Shajuanna Pate, a parent at IDEA Hope near Ybor City, said she had trouble getting the individualized education plan followed for one of her two daughters, who is learning disabled.

Pate said she learned about IDEA from a recruiter who visited her sons’ youth football game. “She seemed very, very nice and she contacted me several times,” Pate said. As both her daughters have learning challenges, she said, “I was thinking they would get more one-on-one there. And that’s not happening.”

She realizes the school still is finding its footing. “I met the principal and I really think he has the best interest for the kids,” she said. But she now sends her daughters to their neighborhood school, Lamb Elementary in Progress Village, and it has been better at meeting their needs.

Math teacher April Cobb moved the two nephews she is raising out of IDEA Hope because, as she explained it, the school was not as well organized as she would like when it came to after-school activities. She now has them at the district’s Jennings Middle School, where she works.

Both Pate and Cobb said they would consider returning to IDEA after the schools are better established. “I pray that they get things together, because they can be a really great school,” Pate said. “But not right now.”

Underwood, the Victory principal, said there have been glitches this year, as would be expected when opening up, brand new, and in a pandemic. She tries not to let them get her down, and said the response from parents has been positive.

“You see passionate people here, working with a purpose,” she said. “It’s a mindset.” Looking ahead, she is planning a grand opening for the school library.

“The thing that is going right,” she said, “is that the kids want to be here.”