Pasco’s pitch to voters: New property tax would help schools compete on pay

Officials contend state allotments aren’t keeping up with expenses, but critics say the money is there.

Tampa Bay Times | By Jeffrey S. Solochek | July 26, 2022

With three weeks until classes resume, schools across Pasco County scrambled to fill nearly 400 teaching vacancies.

Some advertised state-funded signing bonuses to attract new talent. Others turned to social media to tout their positive work environments as a lure.

Even with all the recruiting, the effort frequently foundered. At Pasco High School in Dade City, for example, seven new hires didn’t make it to the first day with students.

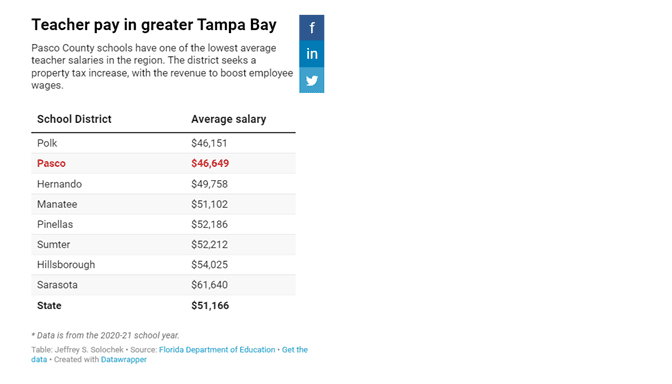

They took jobs with other nearby districts that paid better. According to state records, Pasco’s average teacher salary of $46,649 is $4,517 less than the statewide average, and below all its neighbors except Polk County.

Teacher pay in greater Tampa Bay

“I am worried,” said School Board member Megan Harding, suggesting viable options within the budget had been exhausted. “Our kids deserve to have certified teachers in front of them.”

To become more competitive, the board is asking voters to approve a local-option property tax of up to $1 per $1,000 of taxable value. The revenue would go toward one thing — improved pay for all non-administrative employees in the district. The raises would come in addition to any other negotiated amount, and would have to be renewed every four years.

Both Hernando and Pinellas counties have property taxes to support school employee pay, and Hillsborough — where the average teacher pay is $7,376 higher than Pasco’s — is seeking one in August.

Pasco gave no raises from 2009 through 2013, putting it behind. Since then, its annual increases have ranged between .75% in 2018 to 4.5% in 2014, with a one-time supplement instead of a permanent bump in 2021.

If adopted on Aug. 23, the tax is projected to cost the owner of a $325,000 home with a homestead exemption $300 a year. It’s expected to boost Pasco’s teacher pay by an average of $4,000 a year and the non-instructional staff member wages by an average of $1,700.

The district is working to get some of those employees to a minimum wage of $15 per hour. Hard-to-find bus drivers, for one example, have had a starting salary of $13.40 per hour, compared to $16.04 in neighboring Hillsborough County.

The School Board has cut bus routes and changed school schedules to cope with the driver deficit.

“The stakes are very high for our employees,” said Beth Brown, a retired Pasco educator who’s leading the political action committee supporting the referendum.

Lift Up Pasco, which is run by former district administrators, has collected more than $30,000 — primarily from the employees union, and current and retired district staff — to help get the message out. It’s been making the case that Pasco schools cannot afford to pay more without added local taxes.

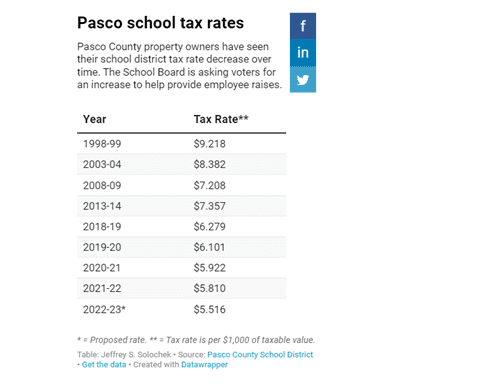

Peaking in 1996 at $9.418 per $1,000 of assessed value, the district’s property tax rate has decreased to a proposed $5.516 for this year, down nearly 30 cents from a year earlier. School district rates are controlled by the state. So, unlike the County Commission, the district may not leave its rate unchanged to take full advantage of booming property values.

Pasco County property owners have seen their school district tax rate decrease over time. The School Board is asking voters for an increase to help provide employee raises.

The state has increased its per-student funding, which led to increases in the growing Pasco district’s bottom line. Enrollment reached 73,578 in 2022, up from 69,217 in 2018, according to the state.

But “the money that comes to us comes with a lot of restrictions,” said Olga Swinson, who recently retired as the district’s chief finance officer. “Once you (account for) that, you’re not left with enough money.”

She spoke of the district’s general operations budget, planned at $848 million for fiscal 2023. The district may not use its $455 million capital projects budget for instruction and related expenses, including such things as bus transportation and food service.

Once the board covers its required and fixed costs, of which employee pay and benefits comprise more than 75%, Swinson said, there’s very little left to deal with. In the 2021 budget, for instance, $57 million was dedicated to school choice programs and $16.5 million to utilities.

If the district were to cut operating costs to make room for pay increases, the most readily available uncommitted fundswould be a pot of money totaling $18.4 million allocated to schools and district programs.Swinson estimated the cost to increase pay 1% across the board would cost about $5 million.

Brown suggested that slashing programs such as Advanced Placement, science fair and industrial certifications would cause rancor among families, while not generating enough to make that 1%.

“Even cutting 10% of those would have detrimental effects,” she said.

There is no organized campaign against the referendum. The opposition that has emerged has circulated in social media groups, and permeated the campaigns of some School Board candidates.

The critics do not deny the need for improved salaries. Rather, they question whether a new tax during a time of high inflation is the best way to accomplish the goal. They suggest the School Board could and should have provided raises within the money it already has available.

District 1 candidate Steve Meisman has contended that employees should not be dependent on voters every four years to continue their raises. He argued at a recent forum that it shouldn’t be difficult to cut 10% from district spending and funnel it into pay.

District 5 candidate Charles Touseull said the board should better prioritize salaries and conduct an in-depth review of all line items to determine possible cuts. He has said the district should consider closing and consolidating under-used schools to save money, and reduce administrative expenses.

State records show Pasco’s per-student spending on administration is below the state average and that of neighboring districts. The board recently merged Hudson Elementary into Northwest Elementary, and has converted two under-capacity elementary schools into magnets to bolster their numbers.

It lists 11 elementary schools, two middle schools and two technical high schools projected to be under 70 percent capacity for the coming year.

“Hard decisions need to be made,” said Chelsi Stahr, a frequent board critic, who noted her child went without a certified math teacher most of last year. “But don’t ask for more money from people who don’t have it.”