An inside look at the private interests shaping public education in Florida

Seeking Rents | By Jason Garcia | July 21, 2024

Florida Gov Ron DeSantis just signed a “potpourri of education reforms” into law. Records show some of the changes were written by Republican donors, for-profit companies, and far-right activists.

It was a simple idea.

Last fall, state education officials suggested that publishers who get approval to sell textbooks to Florida school districts should also be required to provide free sample copies for use in teacher-training programs. The goal was to ensure that Florida’s future teachers could familiarize themselves with the most recent and relevant instructional materials.

It seemed a modest mandate to impose on the school textbook industry, a nearly $5 billion-a-year business. And it was folded into House Bill 1285, an omnibus package of education policy changes that Gov. Ron DeSantis asked Florida lawmakers to make during this year’s legislative session.

But toward the end of the session, the DeSantis administration decided to tweak the proposal. The new version allowed textbook publishers to charge a fee for sample copies — rather than providing them for free.

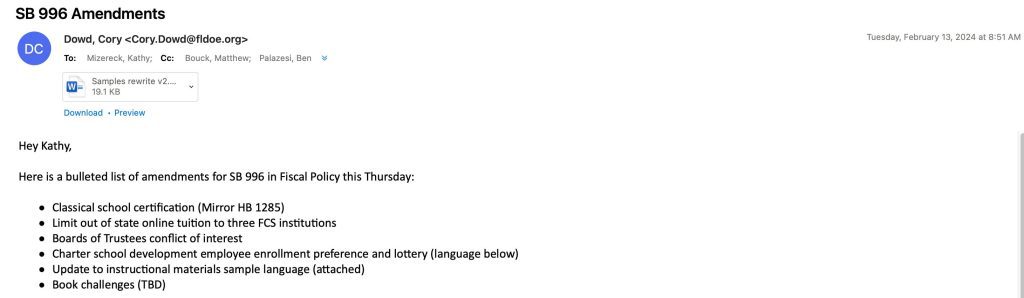

Records show the rewrite was emailed to legislative staffers by Cory Dowd, who was, at the time, a deputy chief of staff in the Florida Department of Education.

But the metadata on the underlying document identify someone else as the original author: A lobbyist for Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, the private equity-owned textbook publisher.

Dowd did not respond to requests for comment. He recently took a job at the same lobbying firm that represents HMH — a lobbying firm that is run by one of Ron DeSantis’ top political fundraisers.

An email from the deputy chief of staff at the Florida Department of Education to the chief education policy advisor in the Florida Senate proposing changes to the Senate companion bill to House Bill 1285.

The episode is but one small example of the ways in which private interest are shaping public education policy in Florida, often in secret. It’s a dynamic that was particularly evident this year with House Bill 1285, which DeSantis described as “a potpourri of education reforms packed into one bill” and was one of the most substantial pieces of education legislation Florida’s Republican-controlled Legislature passed this year.

Lawmakers publicly framed the package as the policy recommendations of the Florida Department of Education and other public officials. “This is the product of a lot of great ideas that have been brought to us, including [by] our fantastic committee staff, DOE, and, of course, the senators themselves,” Sen. Danny Burgess (R-Zephyrhills), said during a hearing on the Senate version of legislation (Senate Bill 996).

But records obtained in public-records requests show that many other politically plugged-in actors had a hand in writing the bill — including a wealthy Republican donor, a private school company, and a far-right policy think tank.

Here are some other examples:

A donor and his school

Such schools have become increasingly popular with cultural conservatives and right-wing leaders who dislike educational programming that elevates other perspectives — especially those of women, communities of color, and LBGTQ+ people.

For instance, Florida currently has 18 classical charter schools operating in nine districts around the state. More than a third of them are affiliated with Hillsdale College, a conservative Christian school in Michigan whose leaders work closely with the DeSantis administration.

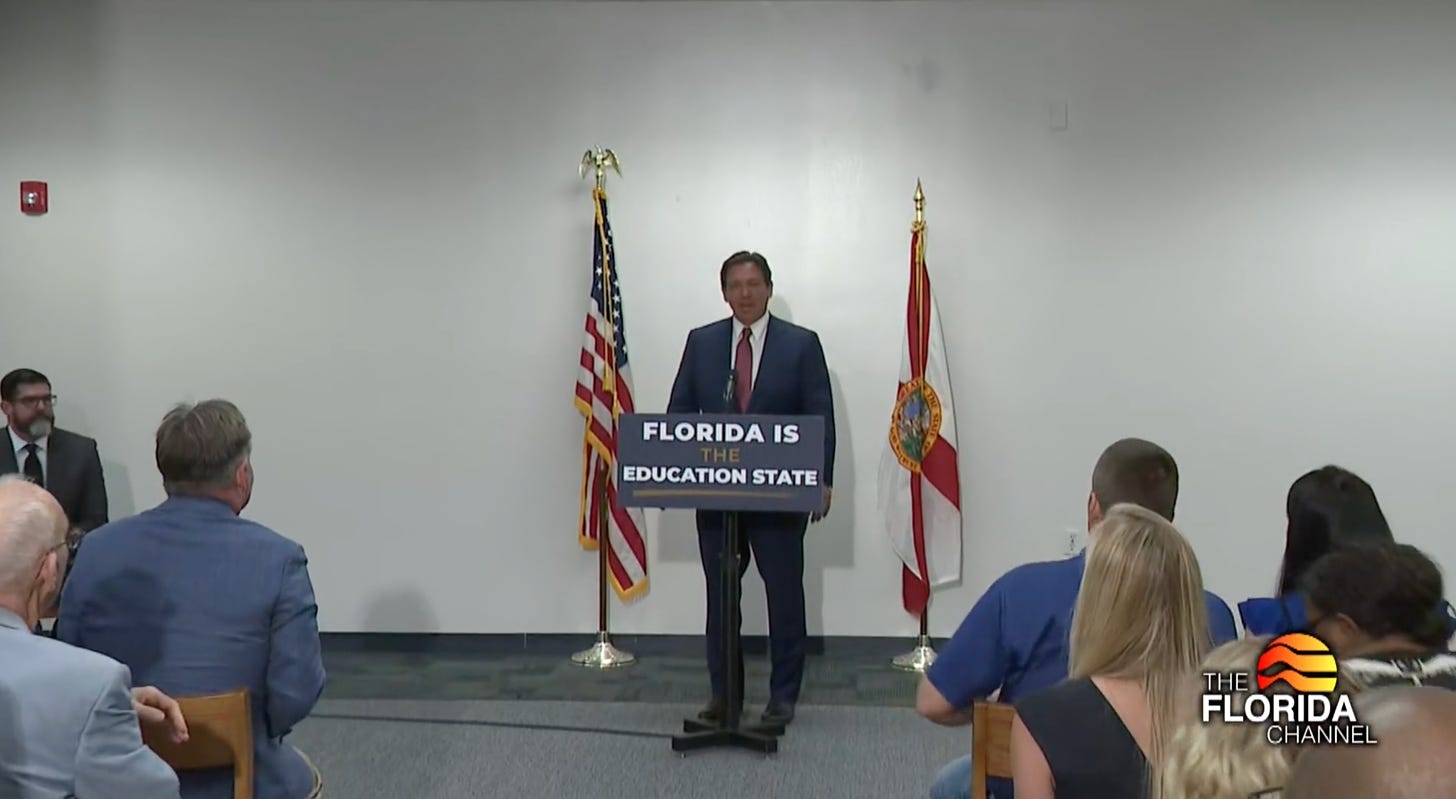

DeSantis signs House Bill 1285 at Jacksonville Classical Academy. (Source: The Florida Channel)

The governor’s decision to sign HB 1285 at Jacksonville Classical Academy made sense for two reasons.

First, two of the more controversial provisions of the bill are designed to boost classical schools. One of those provisions will make it easier for classical schools to find teachers, by allowing them to hire people who lack the full qualifications required of traditional public school teachers. The other will allow classical schools to prioritize children transferring from other classical programs over other kids when enrollment space is limited.

And second, emails show both ideas appear to have been suggested by John Rood, a large apartment developer and Republican Party donor who is also the chairperson of Jacksonville Classical Academy. Few people in Florida have more access to state politicians than Rood, who was once appointed ambassador to The Bahamas by former President George W. Bush and is close with DeSantis, too.

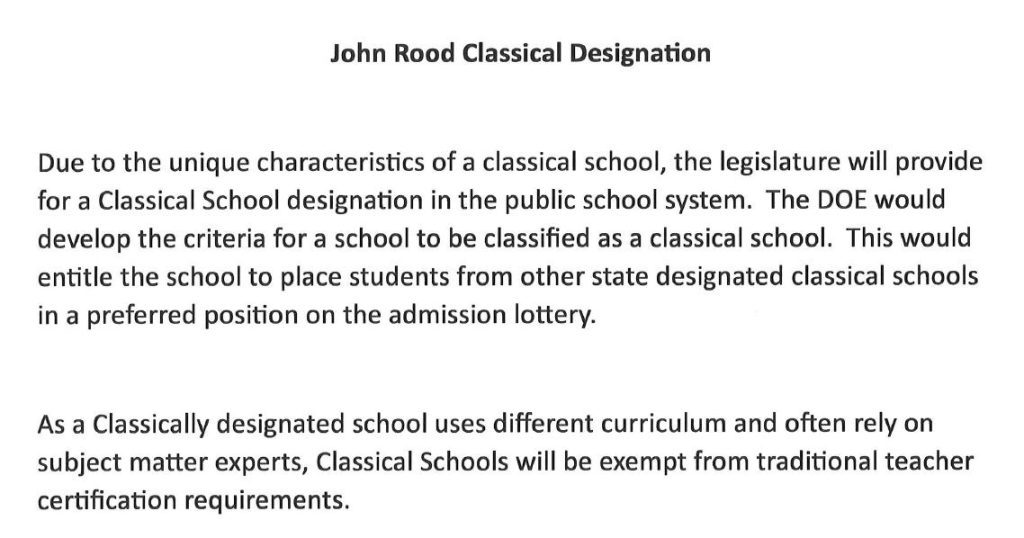

Several weeks before the classical school changes were added to House Bill 1285, emails show that Kathy Mizereck, the senior education policy advisor to Senate President Kahtleen Passidomo (R-Naples), sent a document suggesting the changes to Dowd, the then-deputy chief of staff at the Department of Education. The document labeled the proposals as “John Rood Teacher Certification” and “John Rood Classical Education.”

An excerpt from a document sent by the Senate to the Department of Education.

Another document that Mizereck and Dowd shared with each other grouped the proposed classical school changes together under the heading, “Ambassador Rood items.”

Rood did not respond to requests for comment.

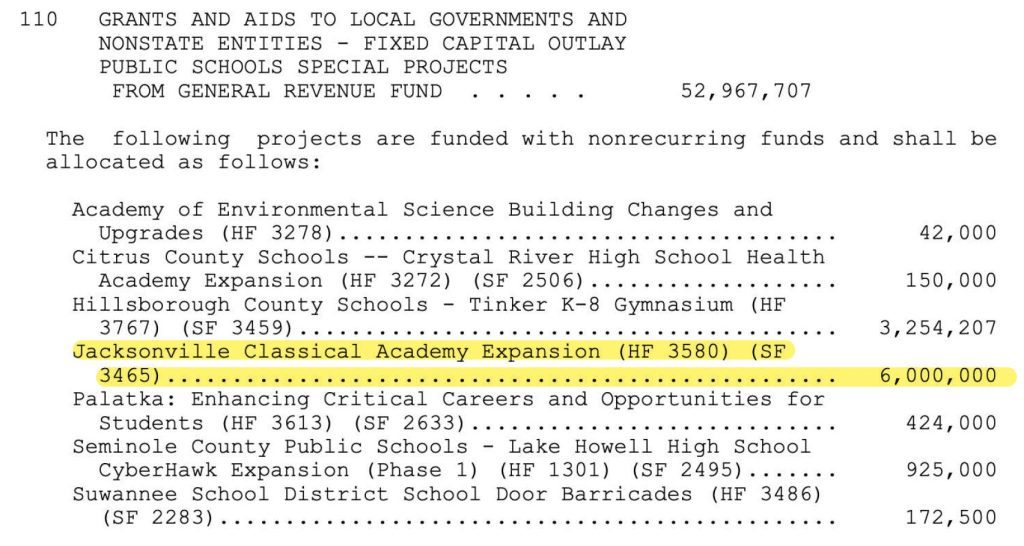

House Bill 1285 isn’t the only gift that his school got from DeSantis and the Legislature this year. The new budget also includes $6 million in taxpayer funding to build a new gym at Jacksonville Classical Academy.

An excerpt from Florida’s 2024-25 budget.

DeSantis recently vetoed nearly $1 billion from this new state spending plan — including money that would have paid for tampons and menstrual pads in high schools, street drainage projects in flood-prone communities, and arts and cultural programming all across the state.

But the governor didn’t touch the $6 million for Jacksonville Classical.

A plugged-in private school startup

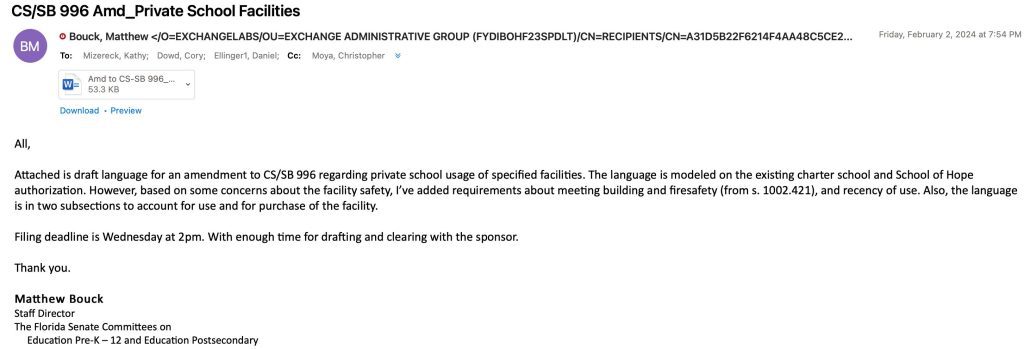

Another part of House Bill 1285 is meant to pave the way for more private schools in Florida.

Specifically, a provision in the legislation will allow private schools to open up in facilities like movie theaters, museums, or churches without first obtaining permission from the local city or county government, in the form of a zoning or land-use change.

Emails show state officials worked on the language with a lobbyist for a company called “Primer,” a start-up that operates tiny “microschools.” Based in San Francisco, Primer’s lead investors include Keith Rabois, a Miami venture capitalist and Republican Party megadonor who has been an enthusiastic supporter of Ron DeSantis.

A lobbyist for Primer was CC’d on draft legislation before it was released to the public.

Opponents, led by the Florida League of Cities, argued the change would rob neighboring property owners and local governments of their leverage to make companies like Primer pay for any potential impacts of new schools — like adding a turn lane or sidewalks to accommodate increased traffic.

But in a written statement, Primer CEO Ryan Delk accused some communities of using “draconian land-use laws” simply to keep private schools out. House Bill 1285, Delk said, will put a stop to that, which Delk said is one of the biggest obstacles to opening new schools.

“We brought together a broad coalition of education advocates, religious leaders, and lawmakers to craft some common-sense policy and get it across the finish line in Tallahassee,” Delk said. “It’s hard to imagine anyone opposing the idea that spaces like community centers, libraries, churches, synagogues, and performing arts centers could be used as schools rather than sitting empty all week — but alas.”

The impact could be dramatic. Primer said the legislation will open up more than 50,000 potential new locations across Florida for microschools. The company also claims that state officials in Texas, Indiana and Utah have expressed interest in passing similar laws.

A far-right think tank

There’s something akin to a tax break in House Bill 1285. But it’s for people who live outside of Florida.

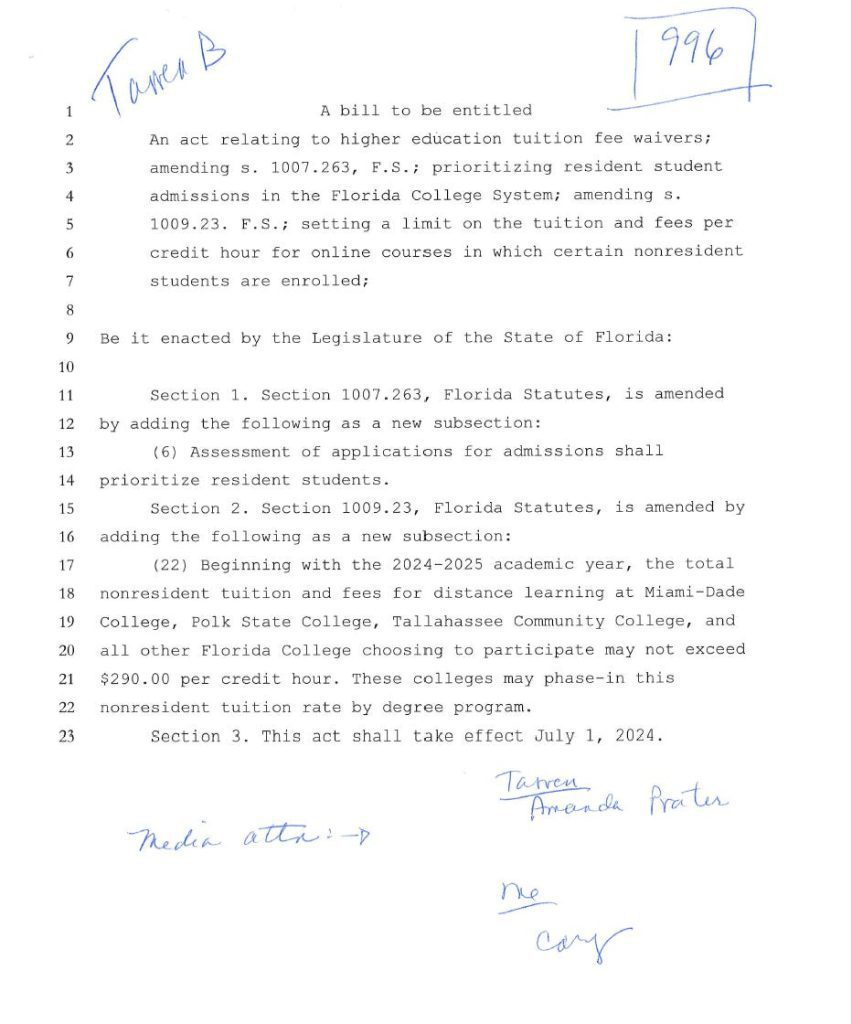

Specifically, the bill requires three state colleges — Miami Dade College in south Florida, Polk State College in central Florida, and Tallahassee Community College in north Florida — to offer discounted tuition to students in other states who wish to enroll in online courses. The price of online tuition for out-of-state students would be capped at $290 per credit hour, a savings of as much as 40 percent in some cases.

Lawmakers said little about the measure when they added it to the bill, beyond vaguely describing it as a “pilot” program to be tested at the three schools. It was never quite clear what prompted it.

But records suggest the idea came from the Foundation for Government Accountability, a far-right policy group that has embedded itself deep inside Florida state government in recent years.

The FGA, whose top funder is a conservative billionaire and Ron DeSantis donor, is best known for cheerleading efforts to weaken child-labor laws, block expansion of Medicaid health insurance, make it more difficult for people to vote, and cut low-income families off from safety-net programs like unemployment compensation and food stamps. But it also gets involved in some aspects of education policy — such as pushing states to eliminate diversity programs in universities and other government agencies.

About a week before the proposed tuition cap surfaced in public, Kathy Mizereck, the education policy advisor in the Senate, emailed a version of the idea to Cory Dowd, the then-deputy chief of staff at the Department of Education who is now a lobbyist.

“I think I was supposed to send you this,” Mizereck wrote in the email, under the subject line “Tarren B issue.”

The top executive at the Foundation for Government Accountability is a former Republican state legislator from Maine named Tarren Bragdon.

The name “Tarren B” was also scrawled by hand on the document attached to the email. So was the name of a former FGA employee who used to work for Bragdon — but now works in the Florida Department of Education.

A document sent to the Florida Department of Education by the state Senate.

Bragdon did not respond to requests for comment, so it’s not entirely clear why the organization wanted Florida to slash tuition for students taking online courses from another state.

But about a month after session ended, the FGA published a new paper praising the change. Now that the DeSantis administration has dismantled diversity programs at Florida colleges and universities, the FGA apparently wants to begin exporting the state’s education programming to more students nationwide.

“No state has gone further to ensure students receive an excellent education, free from radical leftist indoctrination,” Paige Terryberry, a senior research fellow at the FGA, wrote in the paper praising House Bill 1285. “Amid the plague of leftist education policies, Florida’s innovative and refreshing online tuition rate could allow students nationwide to have access to excellent higher education at an affordable cost.”

A charter school chain

The charter-school industry also had a hand in House Bill 1285.

One part of the bill, in particular, arose out of a conflict involving Charter Schools USA, a management company that operates more than 150 schools in four states and is a big campaign contributor in Florida.

The Fort Lauderdale-based contractor spent more than a year attempting to negotiate a contract to take over a struggling middle school in Pensacola but the talks failed — partly because the for-profit company played hardball with the local school district, like demanding 30 years of control over the facility and offering to pay an annual fee of just $1. The governor-appointed state Board of Education eventually came to the company’s side and forced the Escambia County School Board to approve the deal.

House Bill 1285 will permanently strengthen the hands of charter-school companies in future negotiations with school districts over the fate of struggling “turnaround” schools that are to be turned over to a charter operator.

Gov. Ron DeSantis promotes House Bill 1285 during an appearance at Warrington Preparatory Academy in Pensacola. (Source: The Florida Channel)

For instance, the bill requires school districts to more quickly finalize takeover contracts with charter companies. It prohibits them from charging rent or administrative fees. And it shifts more decision-making authority from the locally elected school board to the governor’s Board of Education in Tallahassee, by giving the board the power to develop standardized contracts, facility leases, and maintenance agreements.

The charter-school industry appears thrilled with the changes. DeSantis even invited representatives from Charter Schools USA to join him in promoting House Bill 1285.

“We were the guinea pigs,” Eddie Ruiz, Charter Schools USA’s Florida state superintendent, said during an appearance with DeSantis. “This bill will really open up the red tape that, maybe, is out there.”

A governor and his billionaires boosters

There’s at least one other special interest worth highlighting here.

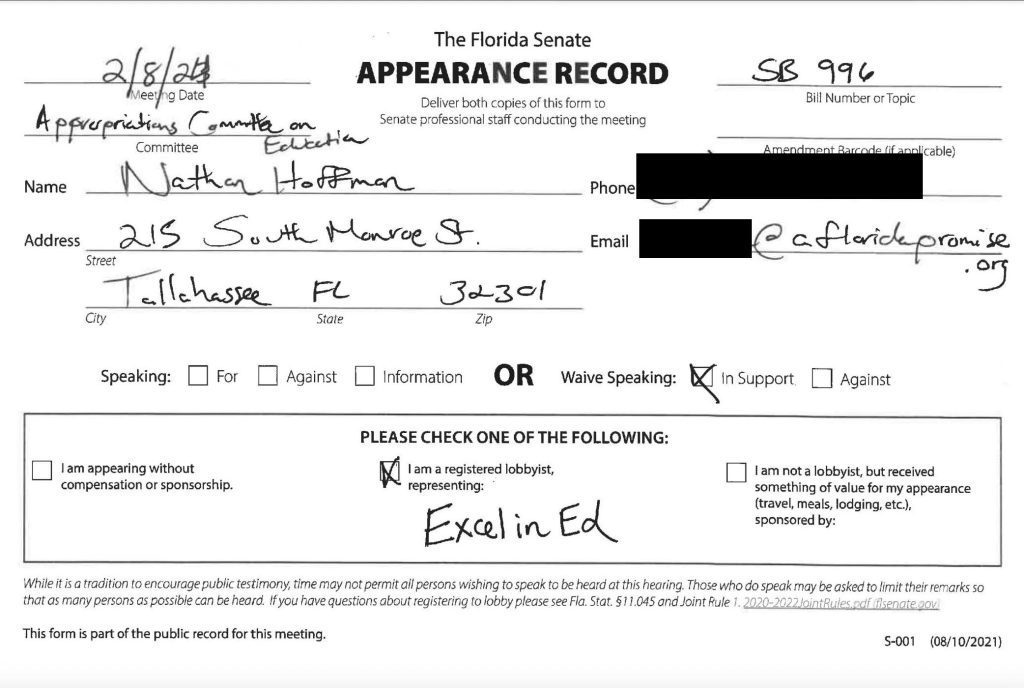

Aside from the DeSantis administration itself, one of the public cheerleaders of House Bill 1285 was “Excellence in Education,” an advocacy group founded by former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush that promotes the privatization of public schools. The organization testified in favor of the bill and promoted it to supporters.

Gov. Ron DeSantis promotes House Bill 1285 during an appearance at Warrington Preparatory Academy in Pensacola. (Source: The Florida Channel)

It makes sense. One of the unifying themes running through the wide-ranging legislation is the way it gives advantages to alternatives to traditional public education — from letting private schools ignore local zoning laws to allowing classical charter schools hire teachers who aren’t qualified to work in other public schools.

Though it’s been nearly two decades since Bush was governor, he remains one of the most influential education policy voices among the state’s Republican leadership.

It helps that Bush is backed by some of the country’s richest conservative donors.

For instance, tax records show that Excellence in Education — which operates through a pair of related nonprofits, one of which also goes by the “Foundation for Florida’s Future” — has received more than $17 million over the past decade from the Walton Family Foundation, the private foundation run by the billionaire heirs to the founder of Walmart Inc.

Bush’s nonprofits have also received sizable donations in recent years from foundations associated the DeVos family, which owns the Orlando Magic basketball team; Charles B. Johnson, the owner of the San Francisco Giants baseball team; Charles Koch of Koch Industries; and Rood, the apartment developer and GOP donor who chairs Jacksonville Classical Academy.

Bush also appears to be getting more explicitly involved in state elections. He recently launched a new political committee in Florida — the Foundation for Florida’s Future PAC — which has showered nearly $100,000 on key Florida lawmakers over the past few weeks, including $50,000 to a committee led by Rep. Danny Perez (R-Miami), who will become speaker of the state House later this year, and $15,000 to a committee led by Rep. Lawrence McClure (R-Plant City), who is expected the become chair of the House’s budget committee.

And where is Bush’s new political committee getting its money? The biggest donor so far is Walmart heir Jim Walton, who has given $200,000.