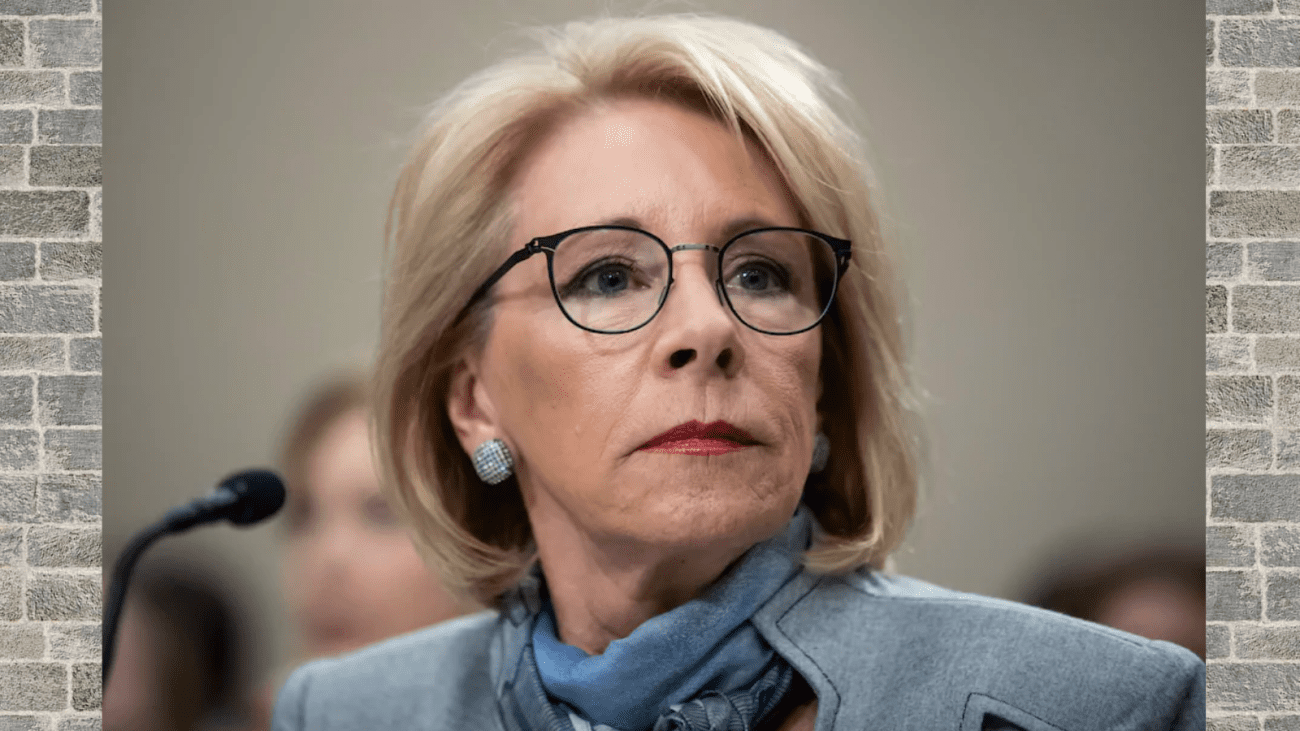

What public education advocates want to see in Biden’s pick to succeed Betsy DeVos

The Washington Post | by Valerie Strauss | November 8, 2020

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos is on her way out of office now that Joe Biden has defeated President Trump, and the education world is eager to see who her successor will be. Whoever it is, Biden has said that the new education secretary will be on a mission to undo things the controversial DeVos accomplished — such as making school choice the primary priority of the department — and work to support traditional public school districts.

Public education advocates are hoping that he picks someone who will bolster public schools, and move away from the past two decades of school policies that emphasized charter schools, standardized testing and operating schools through a business model.

They have been fiercely opposed to DeVos and her agenda to expand alternatives to the public education system, which she once called “a dead end.” Trump voters are likely to be as unhappy with Biden’s selection as public school advocates were with DeVos.

This post looks at what these public education advocates want, written by Diane Ravitch and Carol Burris.

Ravitch is the most prominent public education advocate of the past decade, a former U.S. assistant secretary of education in the administration of President George H.W. Bush who turned against the school reform movement after seeing its effects on teaching and learning. She is an education historian, author and co-founder of the Network for Public Education, a nonprofit advocacy group.

Another prominent public education advocate is Carol Burris, a former award-winning high school principal in New York who is executive director of the Network for Public Education, which opposes the expansion of alternatives to publicly funded and publicly operated schools and districts, including charter schools, which are privately operated but funded with taxpayer dollars.

By Carol Burris and Diane Ravitch

Betsy DeVos just got her pink slip. Throughout her four-year tenure, she did everything she could to undermine public education. Instead, she promoted the idea that schooling should be a competitive free-for-all in which parents shop for schools with tax dollars and then hope it all works out. Now it is time to end that war against public schools as she walks out the door. It is time to chart a course away from the failed reforms that began with George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind (NCLB), accelerated with Barack Obama’s Race to the Top and brought us to the place we are today.

Although education has not been a major focus of this campaign, President-elect Joe Biden, unlike Obama, talked less about “reform” and more about increased support and funding for public schools — an acknowledgment of the critical role that money plays in achieving successful school outcomes. This is a turn from the Race to the Top era during which it was believed, without evidence, that “three great teachers in a row” and the forces of the marketplace could solve all of the problems that American students face.

We are optimistic about the Biden administration. At the same time, we know there is often a slip between the cup and the lip, and while a candidate can say all the right things during a campaign, personnel is policy. It is too soon to know in which direction policy will go. For example, Biden has promised that his new secretary of education would have teaching experience. That is good news. But who that teacher is can make a world of difference.

In our view, whoever Biden picks for the top spot at the department should have a clear record that indicates a pro-public education agenda, as well as an understanding that we cannot test our way to excellence or fix schools by threatening to close them.

Here is what we hope to see in our new president’s choice.

First and foremost, the new secretary must support the rebuilding of our nation’s public schools, which have been battered by the pandemic, two decades of failed federal policy and years of financial neglect. Even as the president heals the nation, the new secretary must heal our nation’s schools.

There is no doubt that our public schools face extraordinary challenges in re-engaging students and families both now and when the virus subsides. The pandemic has expanded opportunity gaps and learning gaps. Even under the best of circumstances, remote learning has been a poor substitute for in-person teaching. In communities where schools opened, the need to quarantine students and teachers exposed to covid-19 or to temporarily shut the school has resulted in interrupted educational experiences. Many districts have been slow to reopen because they lack the resources needed to make the physical space safe. With states’ revenue declining, the federal government will have to provide the needed funds needed to protect the health and safety of students and staff.

Educators will not only have to catch students up academically, they will also be challenged to meet the social and emotional needs of students, many of whom will be traumatized by their experiences during the pandemic. Many will have difficulty adjusting to a return to school. The new secretary, therefore, must acknowledge the impact of adverse childhood experiences and trauma on students’ ability to learn. The financial support dedicated to these efforts must provide flexibility for schools to decide how that money is best spent.

Second, our new secretary of education must recognize that neighborhood public schools governed by their communities are essential to the health of our democracy and the well-being of children. We need a champion of public education in the Department of Education who rejects efforts to privatize public schools, whether those efforts be via vouchers or charter schools.

Choice programs, whether charters or vouchers, result in increased stratification by race, socioeconomics and political points of view. Now more than ever, in a nation divided, we need to increase opportunities for students to attend public schools that build tolerance and understanding of different experiences and opinions.

At a time when so much must be done to rebuild our public schools when covid-19 subsides, our country cannot afford to provide tuition assistance to families that choose private and religious schools. We, therefore, expect that the new secretary will work with Congress to phase out the Scholarships for Opportunity and Results Act, the only federal voucher program, and oppose any congressional attempts to institute tax credit programs that are designed to subsidize private and religious school tuition.

We hope that the new secretary will insist that charter schools be subject to the same transparency, accountability and equity policies as public schools. We expect the new secretary will encourage states to pass legislation putting districts in charge of authorizing charter schools and holding them to high financial transparency and accountability standards. We also expect that the secretary will fulfill Biden’s campaign promise of no federal assistance to charters that operate for profit or are managed by for-profit entities. The new secretary, we hope, will institute a moratorium on new grants from the federal Charter Schools Program at least until those reforms contained in the Democratic Party platform are enacted.

Third, the new secretary must end the era of high-stakes standardized testing — in both the immediate future and beyond. All federal tax dollars must be directed to helping our nation’s public schools recover — not wasted on the creation of new assessments as some have imprudently suggested.

After two decades of school accountability measures based on high-stakes testing, it is clear that these policies have proved to be ineffective levers for improving schools. The use of test results to evaluate teachers and put sanctions on schools has correlated with a decline in student performance on National Assessment of Education Progress tests, which are independent audits of student performance. The rapid and ill-advised implementation of the Common Core and its tests furthered that decline. This administration must focus on opportunity gaps, not test score gaps.

Fourth, the department’s new leader should promote diversity and desegregation (both among and within schools), and commit to eliminating institutional racism in school policy and practices. If we have learned anything in the past election, it is that our country is deeply divided along the lines of class and race. Diverse public schools where students learn together and play together — whether it be in the classroom or on the sports field — can break down social barriers, improve academic performance and increase tolerance. The benefits of attending socioeconomically and racially integrated schools remain throughout life.

Finally, our new secretary must believe in a philosophy of education that is child-centered, inquiry-based, intellectually challenging, culturally responsive and respectful of all students’ innate capacities and potential to thrive.

The secretary must reject the overemphasis on basic skills coupled with teach-the-test pedagogy. As important as literacy and numeracy are, there must be space for the arts, civics, history, second languages and science — all of which have been sorely neglected since NCLB.

Our new secretary must also promote early-childhood education policies that engage children in active learning experiences that enhance their social-emotional, cognitive and physical development. It is not enough to simply expand preschool. We must ensure that all preschools follow the research practices that benefit the whole child.

This is a historic moment for federal education policy. Now is the time to reverse two decades of failed federal mandates. Now is the time for a new vision of what education can be. And most important, now is the time to restore the original role of the federal government as a guarantor of equity, a source of funding for the neediest students and a source of accurate and timely research about the progress and condition of American education.

Photo: Education Secretary Betsy DeVos testifies during a House subcommittee hearing on Feb. 27. (Alex Brandon/AP)