South Florida Public School Leaders Warn: ‘Missing’ Students Could Lead To ‘Draconian’ Budget Cuts

WLRN Sunshine Economy | by Tom Hudson and Jesicca Bakeman | February 23, 2021

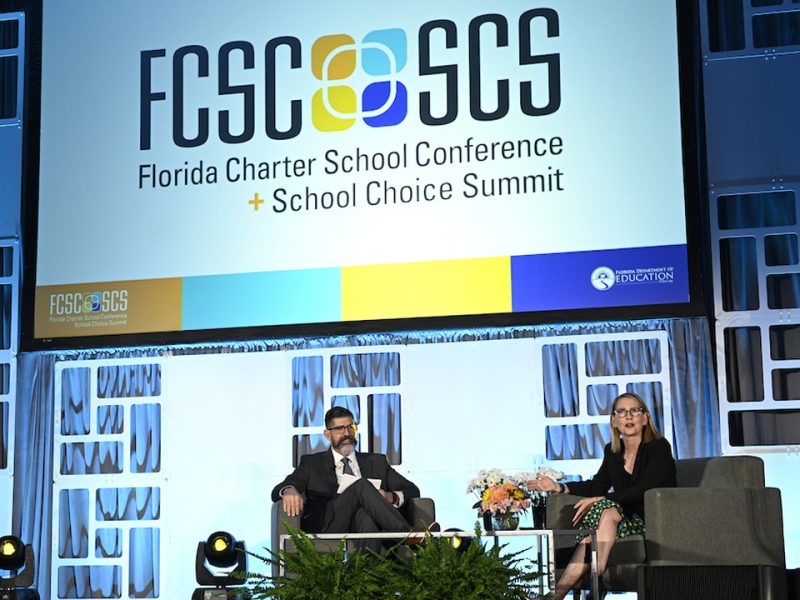

During this special Class of COVID-19 edition of The Sunshine Economy, superintendents of South Florida school districts detail how they’re trying to find thousands of students who aren’t going to school — and what the consequences will be if they don’t.

Public schools in South Florida stand to lose nearly $230 million next academic year, superintendents warned as the state Legislature prepares to gavel in for the first time since the pandemic transformed the lives of Floridians.

The impending budget crisis, brought on by a dramatic drop in enrollment, could lead to hundreds of layoffs, or worse — if school districts are not able to re-enroll tens of thousands of so-called “missing” students.

“If, in fact, these students — the totality of the decline of students from last year to this year — did not return to Miami-Dade County Public Schools in the next school year, we could be looking at a draconian cut,” said Superintendent Alberto Carvalho, who leads the state’s largest school district, during a live edition of The Sunshine Economy.

The program was part of our ongoing reporting project Class of COVID-19, which examines how the pandemic has affected education for the most vulnerable students in Florida.

Statewide, nearly 90,000 fewer students enrolled in Florida public schools this year than expected. So far, the state has agreed to fund school districts based on pre-pandemic enrollment numbers, but that policy appears unlikely to continue next school year.

If funded based on actual enrollment, school districts will see much less financial backing from the state — at a time when they are confronting an unprecedented public health and educational crisis.

Dramatic enrollment drops could lead to ‘draconian’ cuts

If enrollment doesn’t stabilize in South Florida school districts, superintendents estimate the losses could add up to $90 million in Broward, $80 million in Miami-Dade, $50 million in Palm Beach and $7 million in the Florida Keys.

Theresa Axford, the Monroe County superintendent, is planning for a 3% across-the-board budget reduction, including cuts to staff.

In Broward County, the state’s second-largest district, Superintendent Robert Runcie said a “worse-case scenario” would be layoffs in the hundreds.

“I have equated that to the equivalent of closing an entire school zone,” Runcie said. “That’s the high school, the feeder middle school and the elementary. And that means every position from teachers to custodians, bus drivers.

“So that is a huge challenge for us, as we look at trying to stabilize this district,” Runcie said. “The pandemic and the impact of it will still linger into next year.”

Emily Michot/Miami Herald

Palm Beach County Schools Superintendent Donald Fennoy pointed out that his school district, and the ones in Miami-Dade and Broward, are among the biggest employers in their counties.

“If we would have to start laying off employees to account for that, in our context, $50 million dollar shortfall, it would have a ripple effect in our whole community,” he said.

Carvalho, in Miami-Dade, said his district has implemented a hiring freeze and halted purchases of non-essential goods in order to create a reserve that could help prevent cuts next school year.

“I, at this point, do not anticipate a significant impact on educational programs or the workforce,” he said.

The who, what, when, why of ‘missing’ students

Carvalho said enrollment in Miami-Dade district schools is down about 10,000 students, but more than two-thirds of them are accounted for: Many left the county, the state or even the country. At the beginning of this school year, district staff had whittled the number of truly “missing” students down to 1,700.

Alberto Carvalho, Miami-Dade Schools superintendent, talks during a food drive at Citrus Grove Elementary on Wednesday. Pedro Portal

“As a function of the efforts that we deployed, … going into the south, into the west, knocking on doors, collaborating with the Miami-Dade housing authority, as a lot of these families were depending on subsidized housing — we’ve been able to return back to the schoolhouse 700 to 800 of those 1,700 missing students,” Carvalho said.

Aggressive efforts are ongoing to locate the remaining roughly 1,000 students.

In Broward, about 8,400 students who were projected to enroll this year did not show up for school. Nearly 1,000 are enrolled but have not attended classes in person or online, and district officials are still working to track them down.

“The pandemic and the impact of it will still linger into next year.”

Broward Schools Superintendent Robert Runcie

And in Palm Beach County, about 1,500 students remain unaccounted for, Fennoy said.

After efforts to find students who did not return to school in the much smaller Florida Keys district, officials located all but seven kids, according to Axford.

All of the districts have seen big drops in kindergarten, leading them to expect potentially record classes in that grade next year. Leaders said many parents who chose to keep their young children at home because of the pandemic will likely send them to school in the fall.

“A lot of those students are coming from homes just like mine,” said Fennoy, the leader of Palm Beach schools.

“I have two children, one who started in brick-and-mortar on the first day, back in September,” he said. “And this year was going to be the first year of kindergarten for my daughter, and we decided to keep her out for the year.”

In an answer to pleas from Schools Superintendent Donald Fennoy (left) and CTA President Justin Katz (right) and the teachers union, the county health department will offer vaccines to school employees who are over the age of 65. Greg Lovett

The relatively small number of students who seem to have fallen off the grid worry school leaders, since they are the children who faced the biggest obstacles to success in school even before the pandemic upended public education. Children of migrant farmworkers are a prime example.

“I really, truly, believe that, in fact, these are the most fragile of the students that we have because they have a compound effect of so many gaps simultaneously converging upon them,” Carvalho said.

Those compounding factors include poverty, language barriers, homelessness, hunger and fears over deportation and family separation for those with undocumented immigrant parents.

“You really have a perfect storm that is so disturbing to the well-being of children,” Carvalho said. “Even before the COVID crisis, they were already in a deep crisis. It has gotten deeper, darker and much more difficult.”

Miami-Dade and Palm Beach counties have the highest populations of farmworkers in the state.

Fennoy said the district has made some progress helping students with outreach in the Glades, a western portion of Palm Beach County, “but it’s going to be years — truly years — to get those kids caught up, based on the realities of the pandemic.”

What the Legislature could do to help — and hurt

South Florida superintendents offered a variety of suggested solutions to their budget woes.

They include proposals school district leaders make every year: Increasing per-pupil allocations, which significantly lag other large states, plus changes to the state’s school funding formula to account for regional differences in cost of living. Carvalho said that would ensure that “the buying power of educational services is fairly consistent across the state.”

They also argued for some more innovative policy changes, such as restructuring how teachers are compensated to make the profession more attractive and fend off potential staffing shortages.

Also, the leaders said they would like to see the state move away from funding schools based on “seat time” — the amount of time students physically spend in their classroom seats. That’s more complicated now as the superintendents expect some demand for virtual classes to remain next school year, and under existing state policy, districts would get less funding for fully online students.

“You have students who are in a multi-generational family, so there’s still concern there,” Runcie said, offering explanations for why some families would choose virtual school even after the worst of the pandemic is behind us.

“There are also families who have actually adapted and found that the e-learning model actually gives them the flexibility that they need,” Runcie said. “Others say they will not send their kids to school until a vaccine is available and the pandemic totally subsides. So it’s a huge range.”

In the Florida Keys, the number of students learning online jumped from 10 before the pandemic to 370 now. If those students continue in virtual programs, and they are funded at a lower rate than their peers taking classes in person, the financial impact would be significant, Axford said.

“Small things impact Monroe County in very large ways,” she said.

Axford said she disagreed with some legislators’ contention that parents should be punished — maybe even jailed — if their kids don’t go to school.

“We want students back in school, and we want them attending regularly,” she said. “But, I think, to enforce some kind of harsh penalty at this time would be an error.

“We need to get through this crisis before we start to give penalties to people. Families are under a lot of duress.”

Featured photo: More than 27,000 students who were projected to enroll in South Florida public schools this year didn’t show up in person or online. Some are “missing,” and school districts are deploying social workers and police to find them. Camila Kerwin