A School District Announced Guidelines to Protect the Rights of Trans Students. Some Locals Tried to Storm The School Board Meeting.

When locals protested a Florida school district’s plan to protect the rights of trans students, 16-year-old Andrew Triolo decided he could no longer stay silent about his experience — no matter the cost.

BuzzFeed News | by Ema O’Connor | June 8, 2021

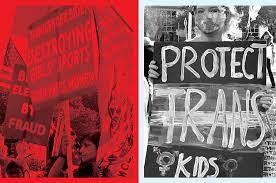

MELBOURNE, Florida — When 16-year-old Andrew Triolo and his mom, Laura Cobb, pulled up to Brevard County’s school board meeting on March 9, there was already a group of protesters outside. One man in a neck gaiter and baseball cap held a sign reading “Straight and Proud.” Another, a kid who couldn’t have been older than 12, held one reading “Pervert Biden Wants Girls to Shower With Boys.” A man with a megaphone yelled anti-gay slurs. He got right in Andrew’s mom’s face and told her she was going to hell, she said. She knew him. He lived down the street.

Andrew is shy and soft-spoken, and often hides his eyes behind his messy dark hair. Just a few years earlier, he hadn’t wanted anyone at his new school to know he was a trans boy, but now here he was about to give a speech to a roomful of people, recounting his experience of coming out. The prospect was nerve-wracking to him — all the more so because this crowd was full of people who, he believed, hated his existence.

He’d prepared a speech in defense of guidelines the school district had recently rolled out seeking to enshrine protections for LGBTQ students, such as allowing students to use the restrooms and locker rooms and play on the sports teams that align with their gender identity, and “decide when and to whom their gender identity and sexual orientation is shared.” The district began working on the guidelines over a year ago, before the sudden sweep of dozens of state-level bills passed around the country regulating the everyday activities of transgender kids. When the Brevard County school district’s guidelines were released at the beginning of March, the new guidelines sparked a backlash, leading to protests at school board meetings and outside the home of one school board member. But instead of stripping Andrew of support and making him feel he had to hide who he was, the fury he faced has only made him and other queer kids in his community more resolved to fight for their rights. Not long ago, Andrew had just wanted to blend in with the rest of the suburban teens in his town, to play sports and go to prom. Now, because of the hate, he has become an activist, organizing in his community and his high school — even at the risk of making himself a bigger target for bullies both at school and around the neighborhood.

After Andrew and Cobb got inside the school board building, the fury simmering around the meeting began to boil over. COVID safety protocols limited the number of people who could be inside the room, so many of the protesters — both for and against the guidelines — who got there late or hadn’t signed up in time were stuck outside, gathered under echoey stone archways. A speaker broadcast the speeches, but the shouts of protesters drowned them out.

Inside the room, standing at the microphone, Andrew shifted nervously in his platform boots. He had been scribbling last-minute notes on the draft of his speech until the moment he addressed the board members and the locals in the audience. Occasionally he paused to make sure he was reading the right part.

“It began with extremely inappropriate issues with my teachers,” he said, recalling the weeks after he came out in eighth grade. “They demanded me to tell them how I knew I was trans, never used the correct pronouns, and started treating me very unfairly in my class after I came out. I was forced to be removed from my favorite subject because of this targeted harassment from my own teachers.”

Then, midway through his first year at Eau Gallie High School, he said, he felt “forced to leave and do virtual school due to discrimination, extreme anxiety, and fear.”

Outside, a dozen or so protesters were trying to get in, but sheriff’s officers were blocking their way. “Let us in,” some chanted, masks off or around their chins, yelling close to the faces of officers. Others shouted about Democratic donor George Soros and former president Trump, and loudly asked those present who supported trans rights, “What are you?” One of the protesters with a bullhorn said, “We’re here to storm the Brevard County School Board.”

One family there in support of the guidelines — Finn Tanner, their partner, Tracy Murphy, and their three kids — was stuck outside when some protesters started banging on the glass windows of the building and rattling the doors.

“We were all huddled together, cowering,” Murphy later recalled. “It was deafening under there; with the banging and the screaming and the megaphones echoing in the arches, we had to scream to hear each other.”

That was the first time in years that Tanner had seen their 12-year-old son cry. Their 14-year-old, Aria, who is nonbinary, almost began hyperventilating at some points.

“I think it was sort of a paradigm shift from, we talk about these things, we see these things in the news, versus like, this is our reality, this is what can happen to people who have families like ours,” Murphy said. “I think this was the first time this became true for them.”

Brevard County comprises a large sprawl of towns and small cities about an hour from Orlando. The school district for the county spans at least 84 schools and around 70,000 students. Florida’s counties elect their school board members, and though the seats are officially nonpartisan, the elections have become no less politicized than the country at large. In the 2020 presidential election, 57% of the county voted for Trump.

In 2016, when the school board first expanded its nondiscrimination policy to specifically apply to LGBTQ students, opponents came out in force at the public meetings to denounce the decision. Some said the policies were against their religious beliefs; others said they were concerned that this expansion, which did not directly address bathrooms or sports at the time, was the start of a slippery slope.

“These policies would allow a boy to blatantly lie in order to go into the girls locker room and lust after them, which is precisely what the slaveholders did,” one middle-aged man said at one of the meetings, which was recorded on video.

The board voted the expanded policy into place 3–2, with multiple members assuring protesting parents that the new policy wouldn’t lead to the concerns they described. (Several studies, including one by UCLA in 2018 and a Media Matters survey of 17 school districts with non-discrimination bathroom policies, found that allowing people to use facilities that correspond to their gender identity didn’t lead to any increase in reports of harassment, assault, or privacy violations.)

Five years later, in early March 2021, the Brevard County school district distributed a new set of guidelines to the administrators of the county’s public schools advising them on the best practices to protect LGBTQ students, along with a sheet detailing the federal laws and court cases to which each policy corresponded.

Over the year the district had been working on these new policies — and gaining speed after Biden won the presidency — Republican-dominated state legislatures suddenly began introducing more than 250 bills regulating LGBTQ people, including what bathrooms and locker rooms trans students can use, whether trans student-athletes can play on the sports team that corresponds with their gender identity (specifically trans girls on girls teams — the bills typically do not address trans boys on boys teams), and what gender-affirming medical treatment trans minors can receive. By May, 17 of these bills had been enacted by governors, which, according to the Human Rights Campaign, broke the record for the most anti-LGBTQ laws passed in one year. In 2020, by comparison, only four anti-LGBTQ bills were signed into law.

In early April, Randy Fine, who represents Brevard County in Florida’s House, cosponsored a bill banning trans girls from playing on girls sports teams and allowing schools to request a medical examination of students’ genitals to determine whether they are eligible to participate. Days after the bill was initially voted down in the Senate, Republican legislators tacked on a similar measure to a bill about charter schools, this time without the medical examination clause. It passed, and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed the bill into law on June 1, the first day of Pride Month.

The snowball of rage that led to the protest at the March 9 school board meeting in Brevard County began with a post about the new district guidelines in a private Facebook group of the local chapter of Moms for Liberty, a “parental rights group” that was founded with the aim of helping parents escalate their concerns to their school boards and districts, its founders said. One of those founders, Tina Chwazik Descovich, then reposted the guidelines publicly on her Facebook page on March 3, and from there it was shared and reshared widely.

Descovich had been a member of the Brevard school board until she lost her seat in the August 2020 election to Jennifer Jenkins, who would become the board’s most vocal proponent for the new guidelines protecting trans students. Descovich founded Moms for Liberty shortly after she left her seat, and in the months since, more than 30 chapters have sprung up across the country.

The group’s primary focus has been fighting masking ordinances and other coronavirus safety regulations in public schools, but chapters function independently from one another, Descovich told me. Some have expanded their causes to include LGBTQ guidelines and fighting against “critical race theory” curricula being taught in public schools. The national Moms for Liberty Facebook page has posted articles falsely claiming that social media and the teaching of “gender ideology” in school “creates” trans teens.

Two days after Descovich shared the new guidelines, Fine posted a video on his Facebook made by Marie Rogerson, an executive board member of Moms for Liberty. It claimed that the guidelines allowed “biological males to use the same restrooms and locker rooms as biological females,” accused the school board of lying in 2016 when it first passed LGBTQ protections, and said that the school district would allow these guidelines to happen without informing parents. The video then gave the time and place of the school board meeting, saying, “Be there. For the kids.”

People left hundreds of comments on both Fine’s and Descovich’s posts, ranging from defending the guidelines to saying they were “Pandora’s Box blown open,” that allowing trans kids to use the restroom of their choice is “inviting [the] rape” of cisgender girls. One person posted a cartoon depicting trans women athletes as giant, veiny monsters intimidating a cis girl.

Descovich said that their members were not a part of the group yelling slurs and attempting to break into the March 9 meeting, and that they do not condone their behavior.

“Obviously, we are for parental rights and liberty and we’re moms and we’re women,” Descovich told BuzzFeed News. “We want girls to be able to compete with — I’m trying to think of the correct terminology here — biological girls.”

Their main issue, four members of Moms for Liberty told me and Fine said in a video posted on his Facebook page, is that they want parents to be informed if their children are struggling with their gender identity or asking to use different pronouns, and they say the guidelines keep parents in the dark. But Janean Knight, a resource teacher for student services for the Brevard County school district, and a spokesperson for the school district, Russell Bruhn, both said in interviews that the guidelines did no such thing — that in nearly all circumstances, the school would contact the parents or guardians shortly after a student initiates a conversation about socially transitioning.

“The only time this would not happen, is if a child says s/he feels their safety would be threatened by a parent/guardian being notified,” Bruhn said in an email. “Our first responsibility is to keep our students safe.”

In early April, a small group of protesters gathered outside the home of school board member Jennifer Jenkins, the most vocal supporter of the guidelines. Jenkins and her 4-year-old daughter were not home at the time, but a video taken by her neighbor shows around 10 people with signs bearing statements such as “Two Genders and One Crazy-Evil School Board.”

At one point, one protester walked toward the person filming saying, calmly, “We got a surprise for you fascist, we got a surprise…We’re putting an end to this … 80 million people are coming for you like a freight train and you’re gonna beg for mercy.”

After the protesters left, a group of locals who supported the trans rights guidelines showed up to write positive messages in chalk all over Jenkins’ driveway. Some in the group, including Cobb and Murphy and Tanner’s family, had never met one another before the backlash against the guidelines had brought them together. They bonded the day of the board meeting, encountering other queer families and inviting them to gatherings with local activist groups or the county’s pride committee.

Andrew and Cobb have keepsakes from these events scattered around the house: Pinned to a wall next to the kitchen is a glove covered in chalk from the messages on Jenkins’ driveway. Scattered on shelves and tables are rocks painted in rainbows from the LGBTQ youth meetup Laura helped organize a week before, and hand-painted posters from the March 9 meeting are taped all over Andrew’s bedroom.

“It was a life-changing day,” said Cobb, sitting with Andrew in his room one afternoon last month as she recounted his speech at the school board meeting.

“I wasn’t really interested in being an advocate before that night,” Andrew said. “And now all of a sudden, I’ve started the Youth Advisory Council for Melbourne, I started the GSA [Gay-Straight Alliance] at my school, now I’m hoping that one day I can pursue a career in advocacy and stuff. I feel like it’s helped me discover my true passion.”

That week, the two of them drove up to another school board meeting. Gathered outside were around two dozen protesters, many wearing Moms for Liberty shirts, holding signs reading “Free Our Kids,” “My Body My Choice,” and “Stop Abusing Our Kids.” This time, the group was protesting mask requirements in schools. “But they probably don’t love gay people, either,” Andrew said as they pulled into the parking lot. He slid down in his seat as the car drew closer and the chants grew louder.

“We know that what we’re doing is important; we know we’re a part of history here,” Cobb said, “but it’s still hard for us sometimes.”

While I was interviewing Andrew and Cobb in their home last month, a man from their neighborhood homeowners association knocked on the door, saying they had to take down their lawn sign. The sign said “Hate Has No Home Here,” with hands holding up rainbow hearts, one of which had “Black Lives Matter” printed inside. At first Cobb took it down, but when another neighbor later put up a graduation lawn sign without complaint, she put hers back up and flew an American flag next to it. The next morning, Cobb discovered that someone had wrapped up her flag in printouts from the Department of Veterans Affairs detailing the proper protocols for flag display. A few days later, she installed security cameras.

When Andrew first came out, he wanted to do it in writing. He wrote an email to his mom while he was at his dad’s house saying, as Cobb summarized it, “I’m trans, but don’t freak out. You don’t have to come over here, everything is fine.” She immediately went over there. They talked it out, then the next day went shopping for boys’ clothes. A few days later, Andrew came out at his middle school, and he started to experience the discrimination and bullying he had talked about in his speech. When he went into ninth grade in a different school, he used he/him pronouns and presented as male, but he was insecure in his own skin and bullied and misgendered constantly. When he told the administration, he said, they did nothing. So he left the school.

One friend of Andrew’s had a similar experience at different public schools in the county. Like Andrew, B. came out to his parents as trans at around 13 years old, but unlike Andrew, he didn’t want to tell anyone. Because B. is not out as trans in his school out of fear of bullying and violence, his mom said, they asked that their names and the schools he attended not be disclosed.

B. didn’t want to come out, but using the girls’ bathroom made him feel anxious, depressed, and disassociated with his gender identity, and using the boys’ was, he believed, too dangerous. So instead, he stopped eating or drinking water during the school day. He was far from alone: around a third of the 27,000 trans adults surveyed by the National Center for Transgender Equality in 2015 reported limiting their food or water intake to avoid using the bathroom. B. lost weight. When his mom picked him up from school he would be starving, parched, and exhausted. Administrators told him he could use the nurse’s bathroom, but it was on the other side of campus, which meant he wouldn’t have time to go there between classes — and, he noted, even the bathrooms in the nurse’s office were separated by gender.

“It was also just the general attitude at the school — kids would make transphobic jokes and drop the ‘f-bomb’ constantly, and the teachers wouldn’t do anything about it,” his mom said, referring to the anti-gay slur. Recently, she added, she’s seen teachers at that school post anti-trans content online about trans kids playing sports and using the bathrooms. She sent me a screenshot of one high school teacher arguing on Facebook against trans kids being able to use the bathrooms of their choice.

The teen’s parents pulled him out of school, and like Andrew, B. took classes using Florida’s virtual schooling program, which has no mandatory video classes or interaction with students, just lessons to read, homework to do, and one-on-ones with teachers. Neither boy felt he could do it for long.

The schools Andrew and B. attended referred questions to the district spokesperson, Bruhn. Bruhn confirmed in an email that the schools were aware of the incidents the kids were referring to, that “district and school leadership address[ed] any student concerns,” and that “we are confident staff at each school have a better understanding of how to make each student feel safe and valued.”

This spring semester, Andrew returned to a public school campus, switching to Satellite High, also in Brevard County. He liked being back in school, he said in mid-May.

He wasn’t experiencing anti-trans harassment from the kids, he said. He was making new friends, and he was planning on trying out for the track team. After he spoke at the school board meeting, he felt his relationship with a couple of his teachers had become strained, but it was nothing he couldn’t handle. He was happy to be in a school that didn’t hassle him because of his gender.

But then, two weeks later, Andrew and Cobb FaceTimed me, sitting on the stairs of their house.

“Andrew got punched,” Cobb said.

“I was literally just walking down the hallway after lunch minding my own business when someone comes up and goes, wham, right in my eye, and then like, walks off giggling and stuff,” Andrew said. “I was just like, ‘Whoa, what just happened?’”

It really hurt, he said, and he went to the nurse to get ice. In a student complaint Andrew filed with the school and sent to me, he said he then told the school’s “resource officer,” who is in charge of managing student behavior, what had occurred. The school investigated, taking statements from Andrew, the kid who punched him, and that kid’s friend, who witnessed the incident. In his statement, the friend called Andrew by his deadname, Andrew said. They had gone to middle school together.

Andrew said he didn’t know and had never interacted with the classmate who punched him. But, according to Andrew, the school is insisting that they were friends and the kid was making a joke Andrew didn’t get. Cobb told me that the school said it had resolved the situation but could not give her any further information.

The following week, a student called Andrew “Madam” in front of the whole class. Andrew said he also reported to school administrators that a girl had repeatedly made explicit comments about his sexuality, saying that being gay and trans was a choice. The school looked into the incident and spoke to the student. She stopped her comments, Andrew said, but she remains in his class.

In an email, Bruhn, the district spokesperson, declined to provide details on how the school handled the incidents Andrew described but said that the school and the district “are aware of the claims and are in the process of finding out the details so we can ensure every student has the best possible experience in our schools.”

“It just keeps happening,” Andrew said. “It’s like I jinxed myself” by thinking everyone was OK in this school, that his troubles being bullied had passed.

“I’m probably not going to be going to Satellite next year,” Andrew said with a sigh. “It’s really frustrating because I really do wanna go to Satellite and stuff, but if this keeps happening and the teachers aren’t gonna take me seriously, and things won’t get done to make things better, then it’s not even worth it.”

“He went back to school because he wanted to have a high school experience, and it’s been a fucking disaster,” Cobb said. “I’m pissed because he wants to go to prom, and he just formed his GSA and he’s very passionate about that, and he wants to try out for sports. He just wants to live a teenage life and he can’t.”

Other teens in the district, and around the country, navigate similar challenges. Some in Brevard County turn to a support program offered at local public schools, Sources of Strength. Knight, who runs the program and was one of the school district employees who worked on the new student protection guidelines, said that she has seen many trans students in Brevard County choose remote learning instead of attending school in person because they don’t feel safe on campus. But, she said, staying home — isolated from friends and sometimes stuck with a disapproving family — doesn’t always offer a respite. Knight recounted one teen whose home environment was so toxic, “it literally took me saying to his mother one day, ‘Do you want to have a funeral now for your child? Because that’s where you’re at.’” A 2021 national survey conducted by the Trevor Project, a suicide prevention organization for LGBTQ youth, found that more than half of transgender and nonbinary minors they surveyed had seriously considered suicide in the past year, up 12% from their 2020 survey.

“We’ve seen so much more anxiety lately, so many issues with mental health they’re struggling with, and this isn’t just COVID stuff,” Knight said. “Kids have heard rhetoric and seen things that are so hateful, their anxiety is at a different level. And then it’s compounded by COVID, by isolation.”

To Knight and other proponents of Brevard County’s protection guidelines, the new standards aim to help kids like Andrew and B. feel more comfortable going to school in person, knowing that there are official rules to point to if their rights are violated. Other school districts in Florida with similar LGBTQ protection guidance, including Lee, Flagler, and Pasco counties, have also faced pressure from groups opposing the language. The Lee and Pasco school districts backed down, scrapping or, in Pasco’s case, diluting the guidance. But Brevard County held strong. The guidelines are still in place for the tens of thousands of students and more than 80 schools in the district, including Andrew’s and B.’s.

June 3 was Andrew’s last day at Satellite. This week he is getting top surgery, something he has been looking forward to for years. After he recovers, his plan is to “enjoy the summer,” he said, “for the first time in a while.”

He and his mom plan to go to Asheville, North Carolina for vacation. What’s in Asheville? “Happiness, love, peace,” Cobb said.

“All of our favorite things,” Andrew chimed in. “It’s really gay there. Not like here. It’s great.” ●

The US National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. The Trevor Project, which provides help and suicide-prevention resources for LGBTQ youth, is 1-866-488-7386. You can also text TALK to 741741 for free, anonymous 24/7 crisis support in the US from the Crisis Text Line. Find other international suicide helplines at Befrienders Worldwide (befrienders.org).