DeSantis attacks ‘critical race theory’ as state looks to change teaching guidelines

Miami Herald | by Ana Ceballos | June 7, 2021

TALLAHASSEE

Gov. Ron DeSantis is sowing division in Florida’s education system as he targets the concept of critical race theory in the classroom and on the campaign trail, an effort that educators and Democrats, many of them Black, view as a political attempt to “whitewash” and suppressdiscussions about race.

For several months, leading up to the governor’s re-election bid in 2022 and what many believe is a future run for the White House, DeSantis has latched onto a trend coursing through national conservative politics and directed his ire toward the theory — a legal academic concept that examines systemic racism in American institutions and policies — because he says it is an attempt to indoctrinate children against the United States.

The theory is not taught in any Florida school districts, state officials acknowledge. Still, DeSantis is repeatedly injecting it into discussions about how teachers should deliver lessons on civics and history to more than 2 million public school students in Florida. Appearing on Fox News Saturday night, DeSantis said he would start getting involved in school board races to attack candidates who support the education approach.

“We are going to get the Florida political apparatus involved so we can make sure there’s not a single school board member who supports critical race theory,” DeSantis said.

But it’s not just chatter on the campaign trail. The State Board of Education is set to consider a rule on Thursday that would place strict guidelines on the way teachers deliver U.S. history lessons, an administrative move that DeSantis says is meant to combat critical race theory in the classroom even if the rule does not mention the concept in writing.

The push to impose restrictions on how teachers discuss race in the classroom comes a year after Americans — among them students, parents and teachers — have faced constant reminders of simmering racial tensions that have been in the forefront of national politics in the wake of George Floyd’s killing.

“We’re supposed to be in this period of racial reckoning and reconciliation and we can’t necessarily agree on how to introduce quote-unquote facts to children in a way that informs them of the realities and prepares them for global citizenship in the 21st century,” said Kideste Yusef, the chair of Bethune-Cookman University’s justice and political science department.

Many educators, such as Yusef,contend that politicizing education policy will hurt students by limiting what and how they learn about racism’s reach out of concern or fear that students may feel uncomfortable.

“Are we not strong enough as Americans to dissect our own history and learn from it?” Yusef said. “Education is engaging intellectual curiosity … if we teach one rigid way, how do we develop those critical thinking and assessment skills?”

DeSantis, meanwhile, says teaching concepts that center on race is a non-starter for him, in part, because it could lead white kids in particular to see themselves in a “negative light.”

“You teach the facts. You teach everything that has happened. But critical race theory is basically race essentialism,” DeSantis told reporters last month. “It teaches people to view that as the most important characteristic and obviously, if you are of certain races — Caucasian or whatnot — they view that in a negative light.”

OMISSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

The problem is that many historical facts have been omitted from the state-approved academic standards and history books teachers use to guide their lessons, said Dr. Bernadette Kelley, the director of the African American History Task Force and a faculty member at Florida A&M University.

“As far as African-American history is concerned, they have not included all of the facts about African-American history. They have omitted a lot of the history and contributions of African Americans in the state of Florida to the U.S. and to the world,” Kelley said in an interview. “To me, that is a denial of some of the facts.”

Yusef agrees. She says the standards elevate some perspectives more than others, and that it often excludes African Americans’ contributions.

“They’re going to read about Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King,” she said. “But I think there is more of an intent to include certain perspectives. There is not an attempt to challenge or even understand the whole nature in which this is taught.”

And if there is a push to include more world views, it is “somehow anti-American,” she said in reference to the governor’s recent efforts.

That’s not to say that African-American history and race relations are not taught in public schools. A 1994 state law says African-American history has to be taught at all grade levels, and the African American History Task Force helps guide that curriculum.

But even with a state law requiringsuch instruction, the vast majority of school districts have yet to fully follow the mandate. Only 11 of Florida’s 67 school districts meet the seven criteria needed to be identified as “exemplary” under the task force’s guidelines, Kelley said.Districts in Miami-Dade, Broward, Hillsborough and Pinellas counties are among those considered “exemplary.”

The criteria includes requirements that districts show they offer teachers ongoing training on the subject matter, have documented evidence that lesson plans are being carried out and that resources are being devoted to deliver the instruction.

An Orlando Democrat, state. Rep. Geraldine Thompson, tried to pass legislation earlier this year that would have required the state Department of Education to verify public and private schools that receive taxpayer-funded school vouchers are carrying out the mandate to teach the history of African Americans and the Holocaust. The bill never got a hearing and it died.

“If you don’t put any teeth into it, and there’s no repercussions behind it, it’s hard to get those school districts,” said Tony Hill, a former state senator and the chairman of the task force.

Hill said hehas found over the years that districts in more diverse communities “absolutely” tend to be more welcoming of African-American history lesson plans.

While progress on the subject has been made on expanding in the state, he says the task force is “doing it inch by inch.”

Sen. Randolph Bracy, D-Orlando, says it is a constant struggle to get the Republican-led Legislature to consider enhancement to the African-American history curriculum.

“There has been progress, but there’s had to be a fight to get the Legislature to move on these issues,” Bracy said. “I would hope that you wouldn’t have to push it and try to force it in people’s faces to say, ‘Hey, this is important’ for them to acquiesce.”

This year, Bracy was able to get $1 million in state funding for a film about the 1920 Ocoee Election Day Massacre. The film — pitched as “an honest recognition of our past” — would have narrated how African Americans in the tiny citrus town of Ocoee were killed, beaten and driven from their homes by white mobs angered by a Black man who had helped Black citizens register to vote and pay poll taxes.

Bracy said there was a plan in motion to get the film shown in Florida classrooms and to a wider, national audience through other platforms. He said a “major distribution” deal for the film was in the works.

But DeSantis vetoed the project last week. The governor’s staff didn’t call Bracyabout the veto or tell him why. DeSantis’ office has not responded to requests for comment on the reasoning behind any of the governor’s vetoes.

The move, however, did not come as a total surprise to Bracy.

“He has been very vocal about not really wanting for us to teach about race in our schools, so that could be his reasoning. But without hearing from him, I wouldn’t know,” he said.

A REFLECTION OF ‘EVERYONE’S VALUES’

In recent days, Florida education officials have been touring the state gathering public input on proposed revisions to the state’s academic standards, which make no mention of critical race theory, even as the governor rails against the concept.

One of the stops was at Miami Jackson Senior High. It was sparsely attended, but the proposed changes to the civics and government standards drew some backlash from members of the public.

“These concepts I feel like my grandmother would’ve taught in the 1940s,” said Robin Porter, a social studies teacher at Nautilus Middle School. “It’s whitewashed. Literally whitewashed.”

Some lambasted the absence of the word “slavery” from the standards. When asked about it, Florida’s K-12 chancellor, Jacob Oliva, told the Miami Herald the education department is doing a listening tour to gather input because there are a lot of points of view.

“Our goal from the beginning is to be transparent,” he said. “The final product reflects everyone’s values.”

The standards only mention the Civil War once in reference to states’ rights. In Miami, some took issue with not teaching about the “pluses and minuses” of communism and socialism. For instance, one standard says teachers must “explain the advantages of capitalism and a free-market system over government-controlled economic systems (e.g., socialism and communism) in generating economic prosperity for all citizens.”

The standards also say students will learn about how different groups of people — including African Americans, immigrants, Native Americans and women —had their civil rights expanded within the context of “legislative action… executive action… and the courts.” They also include the “importance of political and civic participation to the success of the United States Constitution.”

“Yes, it was civic participation … but it’s a total lie to tell children that we only walked down the streets singing ‘We Shall Overcome.’ They need to know that it came on the heels of people like Emmett Till being accused of sexually harassing a white woman,” said Senate Education Committee Vice Chair Shevrin Jones, D-West Park.

Jones, who is a teacher, said it is “baffling” to see the governor’s arguments against critical race theory.

“Republicans, they can do a lot, and they can do whatever they want to do. But you can’t try to whitewash history. You can’t make it seem as if we got here, peaches and cream,” Jones said. “Let’s talk about the facts that led us to this point.”

The proposed standards also include instruction on how individuals can be denied or have their civil rights limited. In particular, how individuals can lose their right to vote for a felony conviction and “limits on the type of protesting,” two issues that have been limited through policy since DeSantis took office in 2019.

THE GOVERNOR’S EDUCATION VISION

DeSantis, who briefly taught history at a private pre-K-12 boarding school in Georgia, has been consistent about elevating civics lessons centered on the U.S. Constitution, a desire echoed by many conservatives across the country.

He talked about it when he was running for governor in 2018, and now again,in the run-up to a re-election campaign.

At the start of the 2021 legislative session, DeSantis tried — and failed — to get the GOP-led Legislature to fund a multi-million dollarcivics initiative against critical race theory.

So now, the governor, with the help of Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran, is turning to the state Department of Education’s administrative process to change the rules on how and what teachers should teach on civics, government and U.S. history.

One of the rules, which the State Board of Education is set to consider Thursday, says teachers “may not define American history as something other than the creation of a new nation based largely on universal principles stated in the Declaration of Independence.”

The rule also would prohibit teachers from sharing their personal views, attempt to indoctrinate or persuade students to a particular point of view that deviates from the state-approved academic standards, which state education officials are in the process of revising.

“The governor and the commissioner have been clear that teachers need to be engaging students in how to think — not what to think,” said Cheryl Etters, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Education. “Standards drive instruction, and anything taught in the classroom must align with those standards.”

Etters said “many prefer to use critical race theory as their guiding star in the debate over curriculum and standards.” She acknowledged that the theory is not in the state-approved standards, as did the governor’s office and Oliva, who oversees the K-12 schools.

But the governor, who sets the strategic direction for education in Florida, “realizes well that CRT has no business in a fact grounded in liberal arts education and that banning it can be both prospective and perspective and there is no contradiction there,” Etters said.

FedIngram, the secretary-treasurer of the American Federation of Teachers and the past president of the Florida Education Association, says the governor’s conversation around critical race theory “seeks to divide people” and is seen by teachers as a “big government takeover of their classroom.”

“We have always trusted our teachers. We understand that they are the experts in how to transfer knowledge into our young students,” Ingram said. “But now, teachers are feeling pressure to follow a script. They are feeling pressure that there’s somebody in their ivory tower in Tallahassee trying to come into their classroom to indoctrinate their children about what they believe is right and now what is right.”

Miami Herald reporter Colleen Wright contributed to this report.

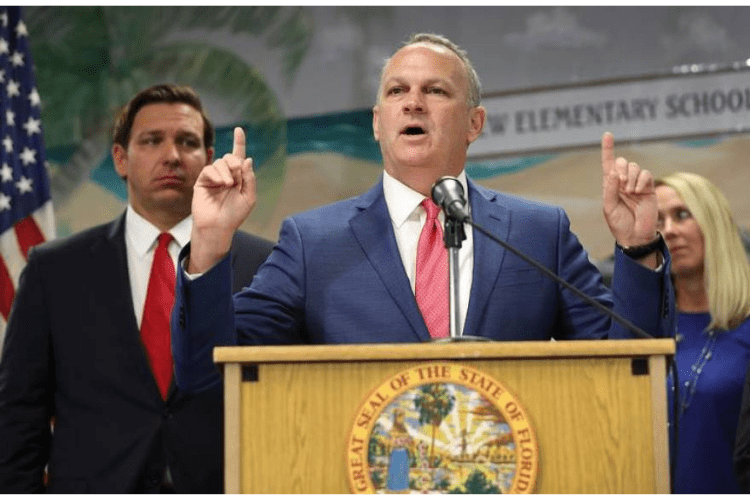

Featured image: On the issue of critical race theory, Gov. Ron DeSantis has said, “We are going to get the Florida political apparatus involved so we can make sure there’s not a single school board member who supports critical race theory.” In this photo from Monday, May 25, 2021, DeSantis responds to local TV reporter’s question after he signed legislation to make it harder for social media companies to punish users who violate terms of service agreements inside FIU MARC building in Miami, Florida. CARL JUSTE CJUSTE@MIAMIHERALD.COM