Florida officials tried to steer education contract to former lawmaker’s company

MGT Consulting, led by former Republican lawmaker Trey Traviesa, was in serious talks to do the work before a bid was announced.

Tampa Bay Times | By Lawrence Mower and Ana Ceballos | January 11, 2022

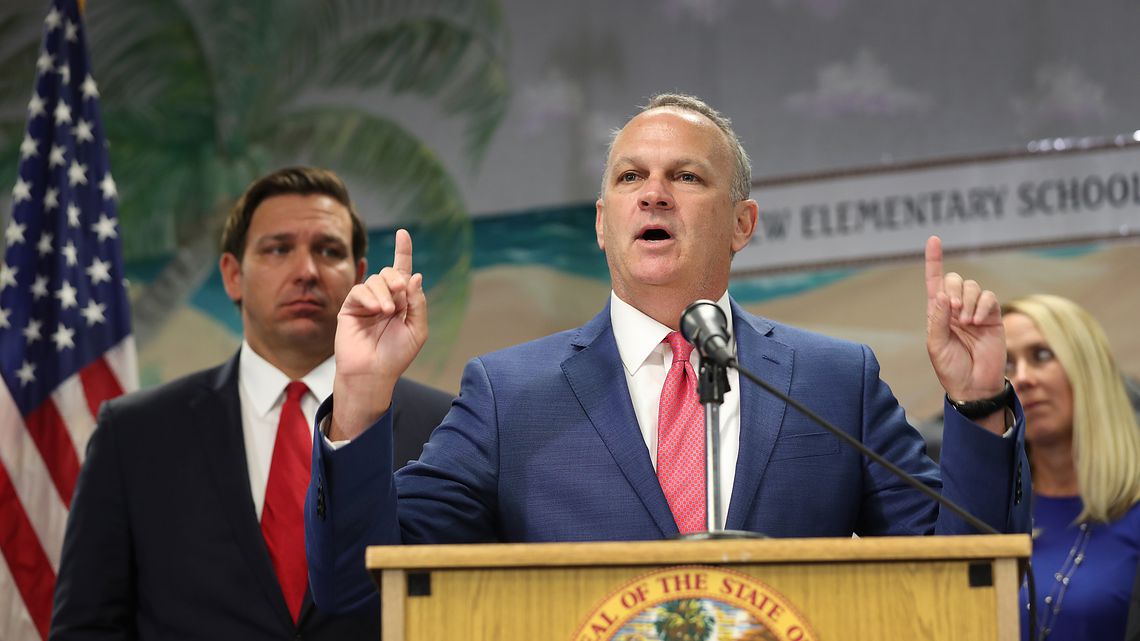

TALLAHASSEE — Gov. Ron DeSantis’ Education Department is under fire for trying to steer a multimillion-dollar contract to a company whose CEO has ties to the state’s education commissioner.

Records and interviews show that, before the Florida Department of Education asked for bids, it was already in advanced talks with the company to do the work, subverting a process designed to eliminate favoritism.

The company is MGT Consulting, led by former Republican lawmaker Trey Traviesa of Tampa, a longtime colleague of the state’s education commissioner, Richard Corcoran.

During a bidding process that was open for one week, MGT was the only pre-approved vendor to submit a proposal — pitched at nearly $2.5 million a year to help the struggling Jefferson County School District with its academic and financial needs.

Documents show the department’s request for proposals was tailored to MGT. But it did not get the award.

Instead, the bidding process erupted in controversy when two of Corcoran’s top deputies and a member of the state Board of Education filed a competing bid. Their effort led to an internal investigation over potential conflicts of interests — and two resignations.

The Department of Education is now conducting a new round of bids for the work. But state Rep. Allison Tant, D-Tallahassee, is calling for an independent investigation, saying that even though the department claimed to have carried out a competitive bidding process, officials “clearly had someone in mind.”

“These guys (MGT) clearly had the inside track to come in,” said Tant, whose district neighbors Jefferson County. “It’s really egregious, in my view.”

Members of the Jefferson County School Board have been outraged for months, seeing the entire process as a way for the state to siphon more money out of a rural, majority-Black school district and into the pockets of the politically connected.

The decision to hire a company to help the three schools — and have Jefferson County pay for it with federal coronavirus relief dollars — came from the Department of Education, they say.

“I’m just going to be honest with you. It’s money,” Jefferson County School Board member Bill Brumfield said in an interview last month. “It’s money and it’s politics, and they are just trying to kick Jefferson County around again like a bunch of little country bumpkins sitting over there and knowing nothing.”

Corcoran said his “first, last and only priority has been to ensure the students of Jefferson County receive the high-quality education they deserve.”

“The Department has followed not only the letter but the spirit of the procurement process,” he said. “Our procurements are designed to attract the widest range of bidders to ensure every needed service is available for every child. Any suggestion to the contrary is uninformed.”

In a statement, Traviesa said MGT got involved at the request of staff at the Department of Education.

“The needs in Jefferson County align with our strengths, and we expressed interest if a competitive process moved forward,” Traviesa said. “Moving forward, the company is reevaluating its participation and will decide whether or not to participate later this month.”

Company had an inside track

Jefferson County, a rural county near Florida’s capital with one of the poorest populations in the state, is coming off the boldest experiment yet in Republicans’ two-decade effort to privatize public education.

In 2017, amid failing grades and financial mismanagement, the state turned over control of the district and its three schools to a private charter school company — the first, and only, district in the state to be privatized.

That five-year arrangement with Somerset Academy Inc. is set to expire June 30, and Somerset opted against extending the contract. Somerset continues to deal with “extreme turnover of instructional staff” and “extremely low proficiency” in math and reading among the majority of students, according to the company’s January 2021 assessment.

The school district was working with the state and Somerset for a plan to take back control of the schools.

Originally, the county’s plan did not include hiring another charter school company to help its transition.

But the Department of Education later decided it would hire a private company to provide assistance with the transition for up to three years, and it would use $4 million of Jefferson County’s federal coronavirus relief money to pay for it.

On Nov. 8, the state announced a request for quotes. The scope was narrow, sent to 25 pre-approved vendors, and all responses were due in one week.

Only one company responded: MGT Consulting.

Based in Tampa, MGT provides consulting services to state and local governments on technology and schools. Since 2009, 10 state agencies in Florida, including the Department of Education, have paid the company more than $11.4 million for various services.

Traviesa, its CEO, is a former GOP lawmaker who was once registered on a business, Step to Success Inc., with Corcoran and his wife, a founder of a Pasco County charter school. The mission of the company, according to corporate filings, was to provide “at-risk students the tools needed to succeed in kindergarten.” (Corcoran said it was a nonprofit.) Traviesa’s business connection with Corcoran was first reported in a Substack postby former Polk County School Board member Billy Townsend.

Traviesa served in the Florida House of Representatives at a time when Corcoran was chief of staff to then-House Speaker Marco Rubio.

MGT had a leg up on the competition for the Jefferson County work: It had been in talks with the Department of Education for at least a week before the procurement was announced, and it was apparently tailor-made for MGT.

On Nov. 1, a week before the state opened the project for bids, the Department of Education hosted a meeting to discuss the transition plan with Jefferson County school superintendent Eydie Tricquet, Jefferson County’s current charter school operator and Traviesa.

Also included was prominent charter school lobbyist Ralph Arza, a longtime close ally of Rubio and Corcoran who resigned from the Legislature in 2006 after using racial slurs during a drunken tirade. Arza has four relatives, including his brother and sister-in-law, working in Jefferson County for the company currently operating the schools.

Arza told the Times/Herald that he was at the meeting on behalf of his job with the Florida Charter School Alliance, which advocates for charter schools, and did not stand to benefit financially if MGT won the award.

On Nov. 5, a Department of Education employee was told to draft the request for proposals. She was given a proposed agreement between MGT and the department and told to base the request for proposals on that document, according to a subsequent report by the department’s inspector general. The employee told the inspector general that Jacob Oliva, one of Corcoran’s top deputies and the head of K-12 education in Florida, gave her the document.

On Nov. 8, the day the request for quotes was issued, Tricquet told the School Board that state officials told her MGT had already been selected and had a contract.

“I do know on Nov. 29, MGT will be taking over,” Tricquet told board members. “I’ll know more when I’m meeting tomorrow with MGT.”

A ‘questionable’ process

State law prohibits state agencies from awarding contracts when a company has an “unfair competitive advantage,” defined as having “access to information that is not available to the public and would assist the vendor in obtaining the contract.”

The fact that state officials were already discussing the work with MGT before it opened the bidding appears to violate the spirit of the competitive procurement process, said Ben Wilcox, co-founder of Integrity Florida, a nonpartisan watchdog group.

“The company could conceivably have gained inside knowledge of what to put in their bid that would give them an advantage over other companies,” Wilcox said. “I think it is really highly questionable.”

Wilcox also flagged the fact that bidding was open for only seven days.

“I’m not surprised there were no other bidders on the contract,” he said. “That would be a really short time frame to put together a bid.”

Corcoran said he was concerned when MGT was the only company that responded.

“When MGT was the only responsive bidder to the procurement, we too were concerned, which is why I personally made the decision to rebid the procurement,” he said. “A competition of one was never the outcome we wanted.” He said there are “at least a handful” of qualified operators who could do the work in Jefferson County.

Traviesa said he did not speak with Corcoran while the bidding was open.

A competing bid by department insiders

MGT might have won the bid if not for another proposal throwing the process into disarray.

On Nov. 15, the final day of bidding, a new company called Strategic Initiatives Partners entered a $1.8 million bid for one year of work.

The company was not on the state’s pre-approved list and therefore was ineligible to place a bid. But the company, formed on Aug. 26, 2021, had a trio of founders that included two members of Corcoran’s leadership team: Andy Tuck, a member of the state Board of Education, which oversees Corcoran, and whose daughter is a member of the Legislature; Jacob Oliva, senior chancellor for the department who oversees all public school operations; and Melissa Ramsey, vice chancellor for strategic improvement.

Ramsey was already familiar with the situation in Jefferson County. She had been working with the county on its transition for much of 2021. She oversaw an office that providesleadership training and curriculum coaches for free to struggling schools — the same services that Corcoran’s office was now taking multimillion-dollar bids for.

The unusual situation of three school officials placing a bid for a department procurement triggered an inspector general investigation into potential conflicts of interests.

Ramsey told the inspector general that she didn’t believe it was a conflict because she had no say over who would be awarded the contract — she said she was under the impression that Corcoran would ultimately choose the winner. If she won, she said, she would resign.

The investigation found that Ramsey directed her subordinate, Caroline Wood, to draft the bid proposal for Strategic Initiatives Partners. Wood later told investigators that she “should have known better” when agreeing to do the work.

Oliva told investigators he was unaware his name was listed on the proposal and said he discouraged Ramsey from applying when she approached him about it.

The investigation cleared Oliva, who continues to serve as Florida’s K-12 chancellor. Corcoran, saying he was “shocked” at the submission from Strategic Initiatives Partners, asked Ramsey and Tuck to resign their posts. They did.

Investigators, who did not interview Tuck or Corcoran, considered the investigation over after the resignations.

Thereport never concluded whether the competing bid was illegal or posed a conflict of interests. It also did not explore any potential concerns with MGT’s bid.

Department spokesperson Jared Ochs said the department appropriately handled the competing bid.

“In this case, once a conflict of interest was discovered, it was immediately investigated thoroughly, the department was able to get to the root cause of the matter, and next steps were identified quickly,” Ochs said.

Ramsey declined to comment. Tuck did not respond to requests for comment.

A spokesperson for DeSantis, who appointed Corcoran to be commissioner in 2018, declined to comment.

Jefferson County’s budget at stake

In Jefferson County, the stakes are high.

When the School Board takes over in July, it will have to make do on a roughly $8.5 million budget — about $7 million less than the charter school operator has during its current year, Tricquet, the superintendent, told board members last week.

The district is trying to prevent laying off employees. It can’t afford to spend its $4 million in federal relief on consultants, interim principal Jackie Pons told the board.

Tricquet told the board they should fight back against the Department of Education. She described being at the whim of Tallahassee, expected to sell department decisions that have changed repeatedly over the last six months. The School Board has had no say in those decisions.

“I’m ready to fight for Jefferson County,” Tricquet said. “I’ve been compliant. I’ve been patient. I have not been invited to things, but expected to come back and sell it. I’m done with all that.”

“Enough is enough,” she said.