Florida Pays Teachers $3K For Completing Civics Training. How It Compares to Other States

How Florida, Illinois, Utah, and Texas are approaching civics training programs.

EDWEEK | BY ILEANA NAJARRO | MAY 2, 2023

The first 20,000 K-12 Florida teachers to successfully complete a new state-run civics professional development course, qualify for a $3,000 stipend.

The Civics Seal of Excellence online course, launched this January and led by Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis, marks what some experts call an unprecedented investment in civics education at the state level.

It comes at a time of renewed national interest in the subject after states disinvested in civics and social studies in the 1990s and 2000s. Democratic President Joe Biden’s proposed budget for fiscal year 2024, for instance, includes $73 million to support American history and civics education programs nationwide, the highest such civics budget since at least the 1980s.

But the unprecedented nature of the Florida course isn’t just due to the dollar sum involved.

Other states typically support school districts to choose training, keeping those decisions local. By contrast, the Florida Department of Education—with input from scholars hailing from the conservative, private college Hillsdale College, the nonprofit Florida Joint Center for Citizenship in the Lou Frey Institute, and the private, Christian George Fox University—created its own state training with a key philosophical approach to civics: patriotism as a desired outcome of education.

The online training aligns with the state’s new civics standards set to take effect this fall.

For decades debates about civics instruction have cleaved down a few different issues: how to balance prioritizing patriotism and critique of the country, and whether to emphasize foundational knowledge—like the Constitution and learning how Congress works—or participatory aspects, like local civic involvement and activism.

Florida’s new standards effectively choose a side: They promote American exceptionalism and focus more on foundational concepts, while downplaying simulations, student projects, and other participatory approaches.

The online training also intends to promote civil discourse in classrooms, according to one of the course’s content experts.

As the new civics standards are set to take effect this fall, this July the state also enacted a law limiting how topics of race can be taught in K-12 schools. It is one of 18 states with such legislation in place. The state has since placed additional limits on the instruction of gender identity and sexual orientation.

Florida, historically a leader in civics education, offers a case study for a timeless question: What is the goal of civics education today? And if it’s partly to foster civil discourse, how do states reconcile that with legislative restrictions on certain topics of discussion?

For a snapshot of how states are approaching this query in their civics training programs, Education Week spoke to civics education leaders in Florida, Illinois, Utah, and Texas.

Here’s what they had to say.

Florida: Promoting a specific approach to civics education

The new Florida civics online course adds to in-person training held across the state last summer, which also featured smaller stipends for participating teachers. DeSantis allotted $106 million to the state’s Civic Literacy Excellence initiative overall.

Teachers of any subject can take the new course, which is intended to help them “understand what it means to be engaged and, more importantly, knowledgeable citizens so that they can then pass that along to their students,” said Stephen S. Masyada, director of the Florida Joint Center for Citizenship in the Lou Frey Institute at the University of Central Florida who helped develop the course.

The stipend incentive signals the state’s commitment to civics education, he added, and enrollment was at capacity at 20,000 as of April 11, according to the Florida education department.

“It really is, in many ways, the centerpiece of the governor’s civics education initiative,” Masyada said.

The 55-hour-long course, split into five modules and an introduction, largely focuses on foundational civics content. Some lessons also cover civic engagement including a lesson on teaching citizenship and civil discourse.

In the course, teachers are expected to view professorial lectures, about 20 to 30 minutes long; read across a variety of primary sources; take quizzes; and complete graded short answer responses, Masyada said.

“The responses are about understanding and being clear that you paid attention, it’s not about being required to agree with what is being said,” he said. “And I really love the fact that we do have some ideological diversity in this course and it’s not a ‘just tell us what we want to hear’ type of approach.”

Some question the commitment to ideological diversity due to Hillsdale College professors’ involvement in the course’s creation: five professors from the Christian college teach lessons. Matthew Spalding, professor in constitutional government at Hillsdale College, served as a content expert for the course and was appointed to the board of trustees at New College of Florida by DeSantis.

Shawn McCusker, who wrote a recent book on civics education, worries entities like Hillsdale provide a very interpreted version of civic education, based upon religiosity.

“To what extent is the course built with an intellectual mindset to balance in a way competing ideas that exist in an ecosystem versus a political outcome organized by politics,” McCusker said. “And that’s something that I think if we were to put that to scrutiny, we could say that it’s not a balanced scale.”

The course’s first module includes lessons on the Judeo-Christian influences on the founders, and religious liberty and church-state relations in colonial America. These are topics that have been rigorously debated among historians and within the civics education world.

It is also the only module to include a note saying it contains “challenging content” about the influences on the nation’s founders. “Do not be discouraged by the complexity of these ideas. Watch the videos closely, take detailed notes, and enjoy the challenge of better understanding the Founders’ mind which enabled them to form this great nation we call home,” it says.

The introduction of the course also features DeSantis as the first speaker for a lesson titled “Florida Civics Education Excellence.”

Spalding, of Hillsdale, said in an emailed statement that “The purpose of civic education is to bring students to an understanding of the principles that underpin our nation: What are the ideas and debates that shaped our country? What triumphs and tragedies, sources of pride and shame, do we share as Americans?”

Masyada said he worked closely with Spalding in developing the course.

“And he was very clear about ensuring that this course is not, shall we say, Hillsdale-centric. It is not only providing one sort of perspective,” Masyada said.

Masyada also said he, Spalding, and Mark David Hall, professor of politics at George Fox University worked to include discussions of African Americans and the Civil Rights Movement in relation to the foundation and promise of America. That was done, he added, with an acknowledgment of the state’s law restricting how race can be discussed in the classroom.

“I think the course does provide teachers a path forward in thinking about these topics and thinking about how they’re going to approach them in the classroom, because Module Four does not shy away from the impact of racism on African Americans and other communities, pre-Civil War, post-Civil War, and [during the] Civil Rights Movement,” Masyada said. “But it simply makes clear to teachers that they need to teach within a historical framework that is accurate and appropriate.”

Spalding added: “Race is a complicated topic in American history. The best way to contend with it is honestly—by presenting primary documents and factual history to students so that they can come to a truthful understanding of a national history that is not without flaws and mistakes, but that also includes the principles that have allowed us as a nation to overcome those flaws and mistakes.”

Critics like McCusker still question the interplay.

“There is a logical conflict between the idea that we are both going to simultaneously pass laws that limit how you can have conversations about intellectual educational topics, and saying that you’re trying to foster an open, free conversation,” McCusker said.

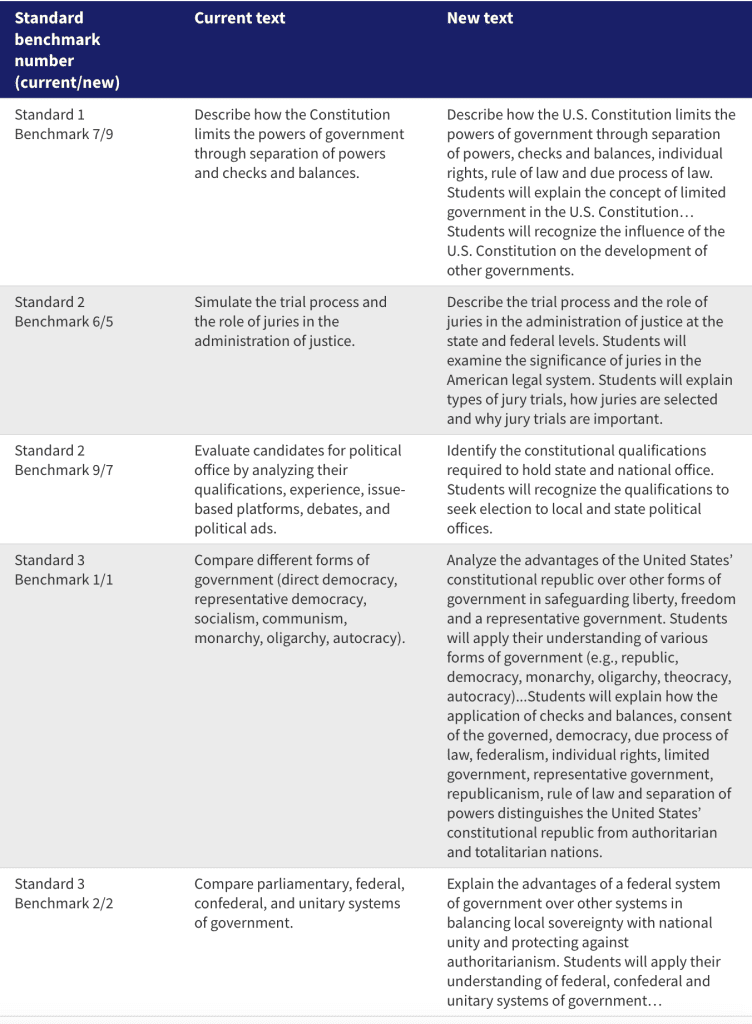

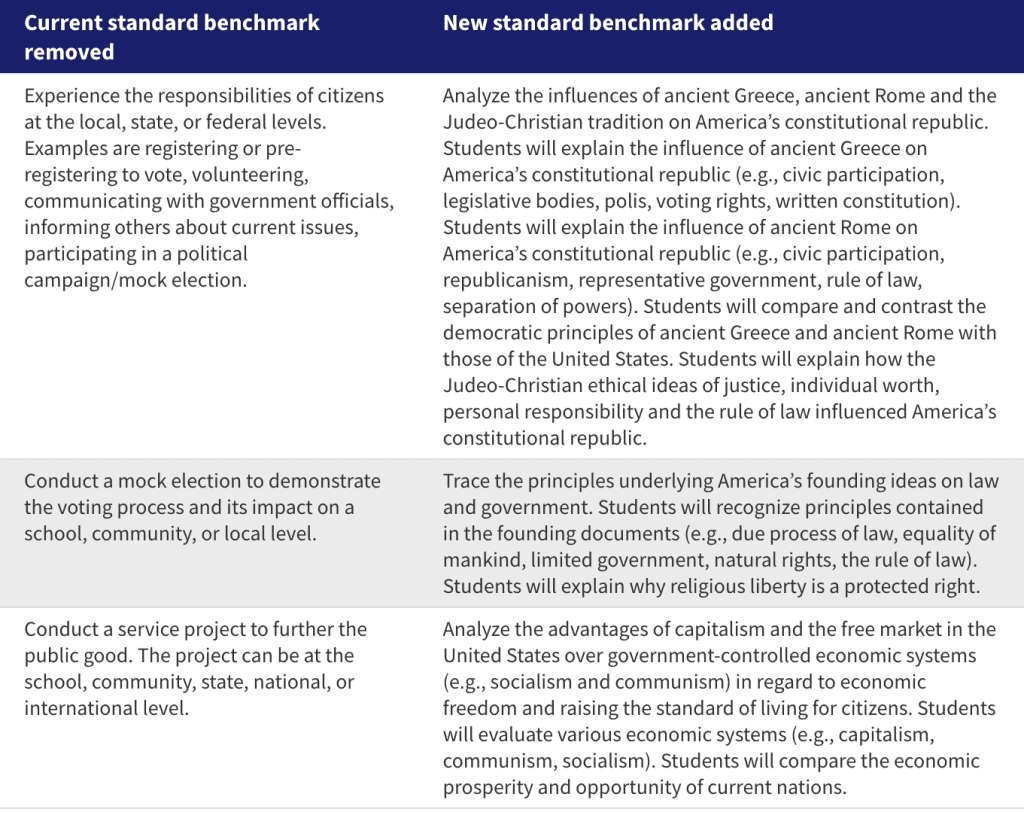

Florida’s Revised Civics Standards: A Brief Comparison

Florida’s revised K-12 civics standards take effect in the 2023-24 school year. Here are samples of the existing civics benchmarks and their revised versions for 7th grade—the year in which students are tested in civics. Some benchmarks were removed entirely, and some new ones were added.

Illinois: Promoting interdisciplinary civics education

When the state of Illinois passed legislation in 2016 requiring at least a semester of civics for high school graduation, nonprofits stepped up with funding to support teacher professional development, said Mary Ellen Daneels, director of the Illinois Civics Hub and Illinois Democracy School Network, which are funded by the Robert McCormick Foundation.

Nonprofits also supported teacher training when legislation establishing a middle school civics requirement passed, said Daneels, who helps schools implement the civics requirements across the state.

State PD focuses more on social studies overall.

That professional development is led by the state education agency and the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign faculty. Two hundred fifty teachers are participating across the state “with a focus on using inquiry-based instruction to support a learning environment and learning experiences that are inclusive of many cultural identities including race/ethnicity,” a spokesperson for the state board of education said.

Illinois’ civics requirements cover instruction on founding documents, including the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, just as Florida’s do. But middle school and high school civics also require current societal issue discussions, simulations of democratic processes, and informed action through service learning.

“I liken it to learning how to drive a car. None of us would give a license to someone for simply passing the rules of a road test,” Daneels said. “To drive a car, you need certain skills and dispositions, habits of mind to do that successfully.

“Likewise, for our youngest citizens, we need to certainly vet them to the rules of the road of our constitutional republic, but also, we need to give them a chance to practice those skills and dispositions as well.”

The Democracy Schools Network—which Daneels leads and is comprised of high schools across the state promoting the idea of civic learning across disciplines—provides stipends to teachers who take five week courses rooted in a nonpartisan approach to civics education.

And similarly to Florida, professional development in civics education is open to teachers of all subjects.

“I think all teachers are really civics teachers, and that all of us send messages to kids about representation, power, and justice in the way we engage student voice in our classroom, the norms we use, the narratives we curate,” Daneels said.

Utah: Worrying over a chilling effect on civil discourse

Civics education in Utah involves “the cultivation of informed responsible participation in political life by competent citizens, committed to the fundamental values and principles of representative democracy in Utah and the United States,” said Robert Austin, humanities team coordinator with the Utah State Board of Education.

Last year, the state started a $1.5 million, three-year grant program funding pilot programs in civics education for local school districts or schools that involved professional learning at the local level, he said. Programming ranges from a simulation of a constitutional hearing to instruction on media literacy.

There is also the Utah Civic Learning Collaborative, which informally brings together nonprofits and universities to share resources and insights on how to promote civics education, including both foundational knowledge and a civic engagement approach.

For example, Utah Valley University, through its Center for Constitutional Studies, offers a constitutional literacy institute every year for teachers to learn more about applications of how to lead constitutional practices in their classroom, Austin said.

The Utah legislature grants the Center about $1 million a year for this training work and other seminars.

Teachers and curriculum directors in the state have also worked with Daneels from Illinois to prepare teachers in Utah for civil dialogue in classrooms.

But in 2021, the Utah state education agency approved a new rule that would limit how teachers can discuss racism and sexism.

Teachers need to help students engage in conversations about civics, and to understand current issues, Austin said. But many feel they’re not sure what they can and cannot talk about in the classroom without running afoul of state rules.

Austin and others within the state advise teachers to stick to standards and be transparent with families and administrators on what they cover in lessons. But Austin said he is concerned that teachers would rather avoid opportunities to have students engage in civil discourse altogether.

“If we don’t help students navigate, talk about, learn about, and think about their role in civic life, and how civics works and how complicated and how hard it is to come together in this country with lots of competing ideas … if you don’t help students navigate that, then you end up with cancel culture,” Austin said. “Doesn’t matter whether it’s on the left or the right or the middle, it’s just students who feel like they should just shut down other voices, instead of listening and then developing a response.”

Texas: Limiting action civics

Prior to the start of the coronavirus pandemic, the Texas chapter of Generation Citizen, a community-based civics organization, was working with school districts in the state to promote student-generated and student-led civics projects, including community organizing on issues students cared about.

Then in 2021, the state passed a law that restricted how topics of race and current events could be discussed in classrooms. It also stated that students can’t be graded or receive course credit for “work for, affiliation with, or service learning in association with any organization engaged in … social policy advocacy or public policy advocacy” among other activities, including direct communication with federal, state, or local level governing bodies.

After consulting with her legal team, Megan Brandon, the Texas program director for Generation Citizen, said the group changed its curriculum, PD, and how it partners with districts.

Student projects that were once community-based are now limited to schools, such as projects revolving around student councils. The organization has also had to modify how these projects tackle topics of race and sex due to the restriction of the law.

“We have to make sure that student discussion sort of falls within these boundaries. It’s definitely not how we would like to approach things,” Brandon said. “And the feedback that we’re hearing from teachers is, that they want more, they’re hungry for more, and that their students are hungry for more.”

The Texas Education Agency did not respond to requests for comment.

For Andrew Wilkes, chief policy and advocacy officer for Generation Citizen, the downplaying of action civics in states like Texas and Florida in favor of more prescriptive foundational knowledge, and the topic parameters set by law, make him concerned for the future of civics education nationally.

“You now see a kind of more truncated, needlessly narrow civics education that, unfortunately, doesn’t let teachers fully live into the fullness of their preparation, as well as it stops students from getting the kind of well rounded hands on civics education,” he said.