Florida teachers are leaving the state and their profession. They blame unrealistic workloads, restrictive laws and stagnant pay.

WUSF | By Nancy Guan | November 30, 2023

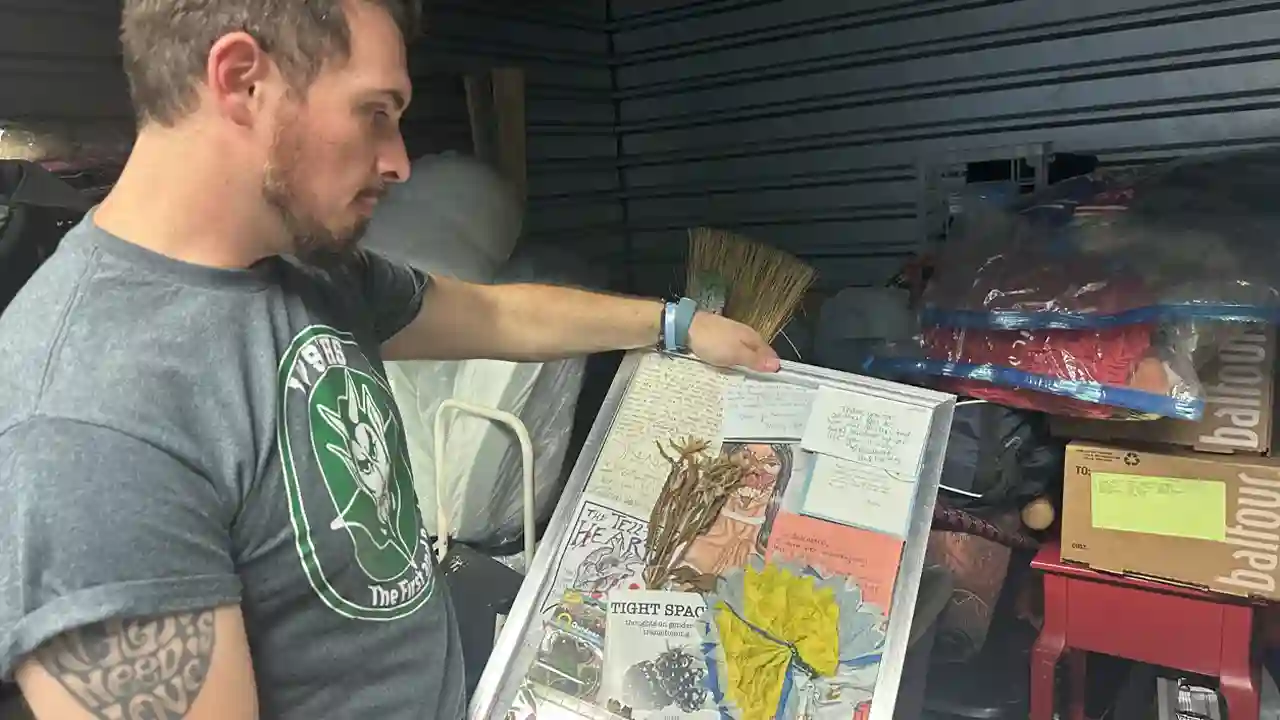

Philip Belcastro looked around at his belongings piled within the storage unit. Boxes of books, a mattress, clothes and old instruments from his past life as a musician were cluttered together.

“This is my entire life in a 10×10 storage unit,” Belcastro said, laughing.

The St. Petersburg High School English teacher moved out of his apartment this summer after rent increased to more than half of his monthly pay.

He was reluctant to leave the community. But the cost of living was squeezing him out. His salary could no longer keep up with the bills and rent.

So he packed up his things, put them in storage and moved in with his girlfriend in Tampa, who’s also a teacher.

But they’re not planning to stay for long.

“I did have to get rid of a lot of things because I’m anticipating — I hope sooner than later — moving out of Florida,” said Belcastro.

“Our job description is to instruct children and make sure that they’re learning in a safe and comfortable environment, which is becoming increasingly difficult for no reason.”

Philip Belcastro

They’re looking at positions in Oregon, where Belcastro has a temporary teaching license, or Philadelphia, where his girlfriend’s family lives.

He admits that rent is likely increasing in other major cities as well, but the Tampa area has seen some of the worst inflation rates. Additionally, the average pay for Florida teachers ranks near the bottom in the nation.

And if pay wasn’t enough of a factor, Belcastro said, the politics are driving teachers like him out of the state too.

WUSF spoke to Belcastro earlier this year about a podcast he hosts with a colleague. They talk about the issues Florida teachers like them are facing — issues that, after three years, are driving Belcastro from the state.

In the last two years, legislation has restricted classroom discussions on race, gender identity and sexual orientation. Teachers are limited on what pronouns they can use or call their students.

A law passed this year (HB1069) mandated that teachers register their classroom books with the district along with school libraries. But rather than risk the increased scrutiny from the state and parents, Belcastro, like many other teachers, cleared their shelves.

“Our job description is to instruct children and make sure that they’re learning in a safe and comfortable environment, which is becoming increasingly difficult for no reason,” he said.

Free speech advocates and civil rights groups have filed lawsuits against laws such as ‘Stop WOKE’ and the Parental Rights in Education Law, known by opponents as “Don’t Say Gay.” The law has served as a model for similar bills introduced across the country.

The impact of these bills are real, said Andrew Spar, president of the Florida Education Association, the statewide federation of teacher and education worker labor unions.

Spar pointed to a growing number of teacher vacancies, nearing 7,000, or 900 more at the start of this school year compared to last.

However, the Florida Department of Education estimated vacancies to be closer to 5,000, as they have a different method for counting open positions.

No matter the number, Spar pointed out that teachers are leaving the profession much earlier. That results in higher turnover rates and less of what are typically considered career teachers.

And Spar said he’s hearing stories of teachers leaving far too often.

“We have fewer people wanting to come into the profession because of the low pay, because of the way teachers and staff are being vilified, so that is creating the perfect storm,” said Spar.

Teachers are finding opportunities elsewhere

“He looked defeated. And I felt micromanaged, insulted and powerless. I could feel, by looking at my student, he felt the same way.”

Jonathan Montesi, former Hillsborough County high school math teacher

But Amica had long been fed up with increasing workloads and years of inadequate pay. She said her job as an ESE teacher at Tampa Bay Technical High School was getting more difficult due to growing class sizes. So, in October, she quit.

“I got tired of looking at my paychecks and then barely covering bills,” said Amica, “And, when your foundational needs are not met, I mean, how are you going to really be good for anything else?”

Amica said she worked seven days a week as a teacher and, on weekends and nights, as a bartender. She rented out rooms in her home through Airbnb for extra income as well.

But, at the same time, her electric bill increased and homeowners insurance doubled. And the $2,000 salary increase wasn’t going to cut it.

So she did the math, and decided to rent out her house and move to Mexico.

“I don’t want my story to be, ‘I had to work six, seven days a week to make it to retirement and keep my house,'” said Amica.

She downsized to a small apartment and is looking for work either in the hospitality industry or teaching English. She said she’s happy with the change — but she didn’t expect it to happen so soon.

Jonathan Montesi, a former Hillsborough County high school math teacher, recently left to work in an IT role at MacDill Air Force Base.

Montesi described what Florida teachers are experiencing as “a death by a thousand cuts.”

After the COVID-19 Pandemic, he worked overtime — 10-hour days, six days a week — to make sure his students didn’t fall further behind. But his efforts were in vain and weren’t being reflected in his pay either, he said.

“We had to do more and more, but nothing else was showing for that,” said Montesi.

Then came a wave of state legislation that restricted what teachers can discuss in the classroom.

The expanded Parental Rights in Education Law meant Montesi couldn’t call one of his transgender students by their preferred name or pronoun without a parent consent form.

“He looked defeated,” Montesi recalled, “And I felt micromanaged, insulted and powerless. I could feel, by looking at my student, he felt the same way.”

Still looking for a way out

Despite everything, Belcastro said he loves being a teacher. His path to teaching was not traditional. He had worked in warehouses, kitchens, retail, and with various non-profits.

But then he fell into a classroom support position with AmeriCorps and thought “this is what I was put here to do.”

Belcastro taught English at St. Petersburg High School while he earned his teaching certificate. In the last three years, the school became his home.

His 2008 Honda is decked out in bumper stickers of the school’s green devil mascot and the teacher’s union. All the beaded bracelets he wears are made by his students.

The trappings of his classroom are buried within his storage unit as well. Some of the books that once lined the shelves now sit packed in boxes.

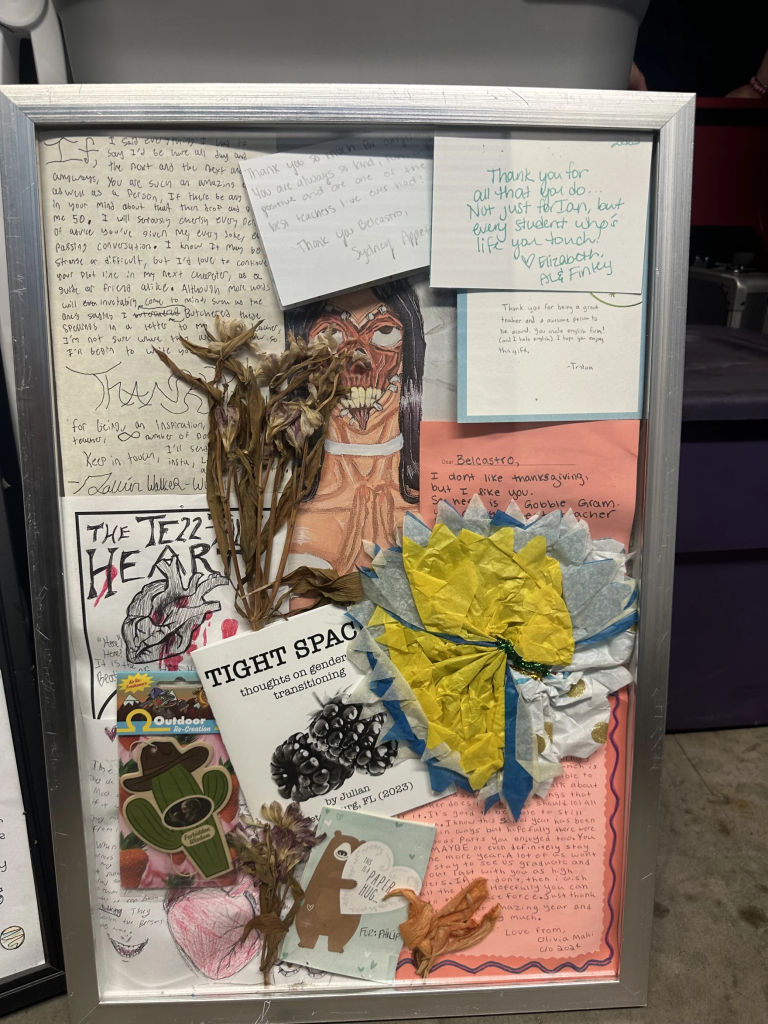

Belcastro pulled several large frames from behind a pile of furniture and clothes. They’re collages of letters, drawings and flowers from students.

Belcastro framed a collage of letters, drawings and flowers given to him by his students.

“I made these shadow boxes of all (my) memories from teaching,” said Belcastro. “This is a student’s final project that they wrote about growing up trans in Florida, especially with all the stuff going on.”

He said the mementos remind him of why he continues teaching. Belcastro read from one of his student’s letters:

“‘You somehow made English class feel like a comedy show, yet also a nice chat with a friend all just by being yourself.’ If all I ever did was make every day for a class feel like a comedy show, I think I’ve done my job.”

He said he misses St. Pete. The reality teachers like him are facing makes him sad and angry, he said, but he thinks it’s time to leave for good.