Florida teachers make their case in court: Keep schools closed for now

Tampa Bay Times | Jeffrey S. Solochek | August 19, 2020

Florida schools are not yet safe for students or teachers, and local officials should have the right to make that call as the pandemic continues.

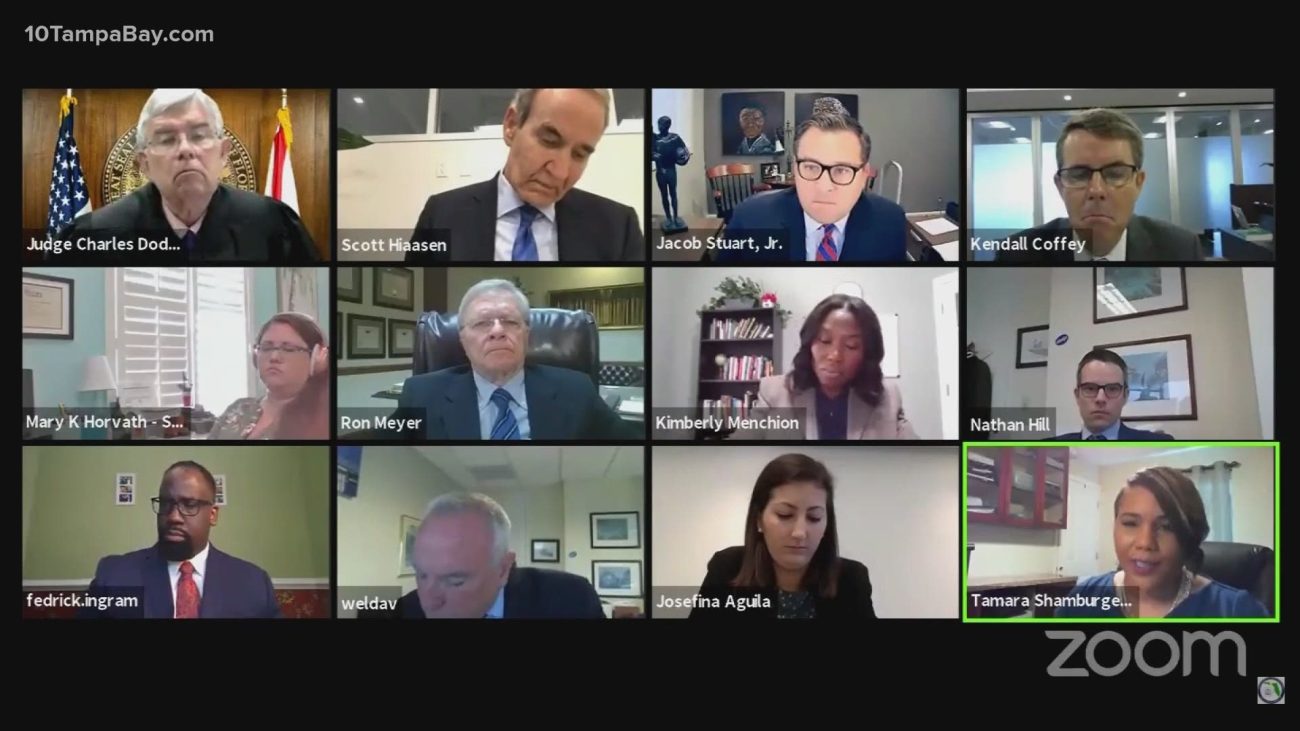

Those were the key points that lawyers for the Florida Education Association and other plaintiffs aimed to make Wednesday, as they tried to convince a Leon County judge to stop the state’s order forcing school districts to open classrooms for in-person learning by the end of August.

“We believe we laid out a convincing case to protect students and the people who work in our schools,” FEA vice president Andrew Spar said in a statement released after the eight-hour virtual hearing, made necessary after the sides failed to reach a settlement the day before.

Judge Charles Dodson had required mediation, suggesting the case cried out for a resolution that both sides could agree upon. Few anticipated a positive outcome, though, as FEA president Fed Ingram and education commissioner Richard Corcoran exchanged barbs on Twitter the evening before.

Even after the end of Wednesday’s hearing, in which the plaintiffs presented their witnesses and arguments, Dodson reiterated his point.

“I would be delighted if I got an email around 8 p.m. … saying y’all had resolved your differences,” he said before closing the meeting with a reminder to return at 8:30 a.m. Thursday.

The lawyers chuckled. But, having spent the previous several hours sparring, none came close to committing.

The hearing began with opening arguments. In forcing schools open, plaintiff’s lawyer Kendall Coffey said, the state is ignoring its duty to provide safe and secure public education.

Florida’s Constitution requires a high-quality education, defense lawyer David Wells countered, and the best place to offer it is through face-to-face learning.

The more compelling arguments came when the witnesses showed up. First to speak was Hillsborough County School Board member Tamara Shamburger, whose district was held out as the prime example of the state overstepping its bounds.

After receiving input from medical professionals, the Hillsborough board voted to delay an in-person reopening for four weeks. Corcoran told the district its approach didn’t meet state expectations, and could cost it millions in funding.

Shamburger said she was “completely shocked,” noting that the state never threatened funding when schools went to all online classes in the spring. She argued that the district tried to follow the rules and guidelines for a proper reopening, based on local needs and constitutional authority, but was overrun by the state.

“Against medical advice, we are going to be putting our students and teachers in harm’s way,” Shamburger said.

Orange County teacher James Lis next testified, airing his concerns about teaching in a “very small (portable) classroom with poor ventilation,” and how he might bring the virus home to his aging mother-in-law. He asked for an online-only teaching position but didn’t get one.

“I’ve chosen my students for so many difficult things. But I can’t put my family at risk,” Lis said. “I would resign.”

FEA president Fed Ingram also offered testimony explaining why his organization decided to sue over the reopening order. He noted that the union appreciated the “show of leadership” the governor and commissioner provided in the spring and wished it would continue into the fall.

The lawyers discussed how state officials said school districts could make their own decisions on reopening if they had “advice and orders” from the state or local health departments, but how those were not forthcoming. Then they introduced two expert medical doctors who painted a dire picture of what they believe could happen if schools reopen under current conditions.

Dr. Annette Nielsen, who served on the Orange County school district’s medical advisory board, described COVID-19 cases in children she had treated, including a 15-year-old who was misdiagnosed in an emergency room and later had a stroke. She said the virus is spreading from children to adults and vice versa, and suggested the state’s dashboard data on cases misrepresents positivity rates because it double counts negative tests, which are required for many to return to work.

“Kids do need to be in school. That is so true. … However, you have to do it in the lens of safety,” Nielsen testified. And right now, she added, “we’re simply not ready. We don’t have the things in place to open.”

Dr. Thomas Burke of Harvard University, who has advised other nations on their COVID-19 responses, furthered the position that schools should not be opened yet. He said it was “exciting” that Florida had seen its virus spread increasingly contained, but worried that the state could see an “explosion” of cases if it reopens schools as planned.

He reiterated the need to have two weeks of consistently reduced positive rates, with an overall rate below 5 percent of people tested. Without that — plus having mitigation factors in place such as masks, contact tracing and adequate regular cleaning — Florida could face a “rapid rate of surge” of the coronavirus, Burke said.

The final witness of the day was Andre Escobar, an Osceola County teacher who has several health problems related to being a quadriplegic, yet was unable to secure a full-time online teaching position. He spoke in detail about his health worries, describing how his school had not offered him any special consideration or support as he prepares to return to a classroom.

So far, he said, the only supplies he received were sanitizer and Kleenex, though he expected more.

Lawyers for the defense used their cross examination to raise points such as the fact that teachers with such situations can file a grievance with the district, and do not need the courts to intervene. Regarding the Hillsborough scenario, they pointed out that the district could have submitted more data to the state to comply with its directive, but did not do so.

They planned to make their full argument on Thursday with witnesses including chancellor Jacob Oliva, a doctor, some teachers and other education department officials.

Judge Dodson said he would leave time for more discussion on Friday, if needed, but hoped to have briefs no longer than 15 pages to his desk by 5 p.m. Friday, so he could issue a ruling early next week.

Corcoran issued his emergency order in early July, instructing districts to open their buildings for classes in August, unless they have an order from health officials stating otherwise. The directive raised concerns among many teachers and parents, who contended that the pandemic continued to make the idea of going to school unsafe.