For 17th Straight Year, Flagler Schools’ Enrollment Fails To Grow Despite Continuing Population Surge

FlaglerLive | June 19, 2024

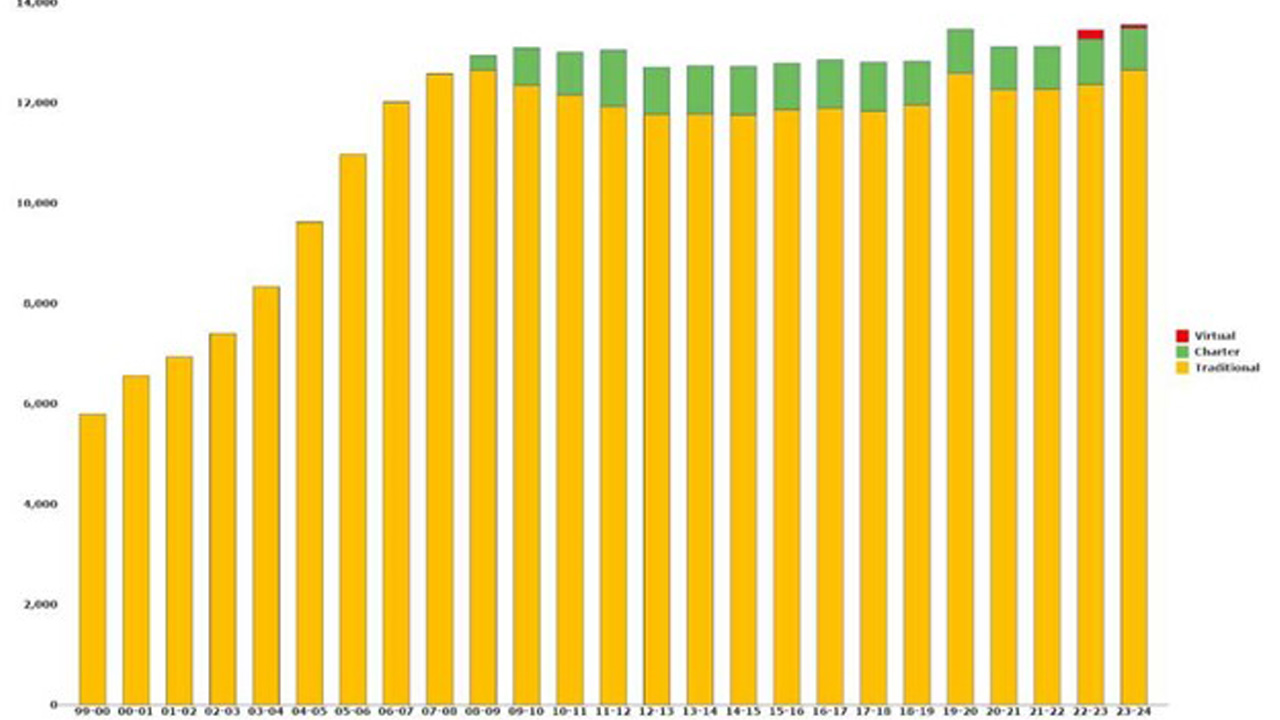

For the 17th straight year, and despite population growth that ranks Flagler County among the fastest growing in the state, Flagler County’s public schools’ enrollment has failed to grow.

At a school board meeting on Tuesday, Board member Colleen Conklin said development in the county was continuing “in leaps and bounds.” She had just attended the periodic meeting of local government representatives to discuss how that development has been affecting school enrollment and the fees builders pay to defray the cost of new schools–if new schools are needed.

What Conklin did not say is that in spite of growth that added 16,000 new residents to the county in three years, in spite of Palm Coast, the county and Flagler Beach issuing certificates of occupancy for some 3,200 housing units in 2023 alone, and in spite of similar growth trends in 2024, Flagler County schools are simply not attracting enough students to reflect that growth.

Students are going to private schools, to virtual schools, and staying home to homeschool: the number of homeschooled students has grown 58 percent in six years, from 706 in the 2017-18 school year to 1,119 this school year. They’re just not enrolling in Flagler’s traditional public schools.

Enrollment in the district’s nine traditional schools in May, at the end of the school year, was 12,659–almost the exact enrollment in the 2008-09 school year. It has fluctuated up and down since, and this May’s enrollment is up by 300 over last year, but it is hardly an increase over pre-Covid enrollment.

Three years ago the district made a big pitch to double school impact fees, arguing that an enrollment surge was coming, that it needed to build a new school by mid-decade, that it didn’t want to be behind. School impact fees are the one-time fee builders and developers pay for every housing unit they build. The fees defray the cost of new school construction. The School Board voted to increase the impact fee, which had budged since 2005, from $3,600 to $7,175.

Builders and the County Commission argued then that 14 straight years of flat enrollment did not support doubling the fees. They opposed that sharp of an increase. School officials considered the opposition deluded and insisted that growth was on its way. How could it not be, with so much construction happening everywhere?

In the end, the county, which had the authority to ratify the new impact fee, agreed only to a fee of $5,450 for single-family homes, with an allowance for a $500 increase for every additional 500 students enrolled. Even that incremental enrollment has not materialized.

The officials gathered around the table at the latest ILA meeting on June 12 were oddly muted about the anemic enrollment. (ILA stands for Interlocal Agreement, reflecting the joint agreement that controls how school impact fees are levied.) All the focus was on growth in general, though William Whitson, the district’s point man on impact fees, said it had gotten money from developers to “reserve” 2,466 student seats in future classrooms, based on developments in the pipeline.

But that number reflects an assumption that has not held true so far. A formula estimates that each new housing unit will generate 0.43 school age students. But the formula does not–cannot–say how many of those students will go to private school, will be homeschooled, will go out of the county, or will attend charter schools.

“This generation rate will probably hold for a year or two,” Whitson said. Like enrollment, it is almost unchanged from 2021. Which means that school-age students have continued to come in. They just have not gone to public schools.

Hunter’s Ridge, the big development at the south end of the county, straddling the line with Ormond Beach, has been growing substantially. But many families choose to send their students to Volusia County. The bus drives to Flagler schools are too long, having to cover a 20-mile distance, when the distance to Volusia schools is a fraction of that.

There was once devoted acreage for a school in Hunter’s Ridge. “That’s gone,” County Commissioner Dave Sullivan said. Only 17 students from Hunter’s Ridge are attending Flagler’s public schools, Dave Freeman said, and only four of those students were taking the bus. “We are looking at an alternative to that next year by using some vans instead of buses to get them a little bit quicker,” Freeman said. Flagler schools are working on an agreement with Volusia County to delineate the line from where, in Hunter’s Ridge, students can normally attend school in Volusia.

Nevertheless, the district’s projection is for either a new middle school or a high school, or both, to open in the 2029-30 school year, according to Dave Freeman, the district’s operations manager, though Whitson later modulated that: “Our new schools, should they come about, are going to be in that 29 to 30, 31 timeframe,” Whitson said.

“Unincorporated county is not generating maybe as much or as many students as other jurisdictions because we’re trending towards more of the larger homes, higher value, particularly in the Hammock area,” Adam Mengel, the county’s growth management director, said. “Those are typically going to be second homes or now retirement homes for those folks moving in, they’re going to have grandchildren versus children in the schools.” The Hammock is also big on vacation rentals.

The county issued 146 single-family home building permits in the nine months from July 2023 to the end of March 2024. In the 12 months ending in December 2023, the county had issued 434 certificates of occupancy–meaning that the houses were ready for residents to move into. Most of those homes are in Hunter’s Ridge.

“We continue to grow like everybody else has been in Flagler County,” Ray Tyner, the chief development officer in Palm Coast, said. In 2023, the city issued 1,339 building permits for single-family homes, and permits for a total of 2,131 units when apartments and duplexes are included. The first three months of 2024 point to a slight decline, but the annualized total would still be 1,916 total units permitted.

So far this year, the city has approved development orders for 742 units in four subdivisions or multi-unit project.

“So all the hysteria that we read about in the paper, Palm Coast is building 9,000 units here, 3,000 units there, that’s all going to take a lot of time,” Flagler Beach Commissioner Jane Mealy said. Tyner agreed, making the comparison with the time when ITT platted 47,000 lots in Palm Coast in the late 1960s, with 20 percent of those still unbuilt. But Mealy had a point: “My question really is, at what point does the school board need to say hey, X number of kids is coming because of that.”

That’s the point of the ILA group and its reports, Tyner said.

“I think people are freaking out because they’re seeing the buildings going up,” Conklin said. “It’s not even so much looking at the permits. They’re seeing massive building projects taking place and popping up.”

They’re just not seeing them go to Flagler schools.