Hillsborough eyes closing, merging schools to help fix budget woes

Schools with too few students will be examined for possible shut downs. Changes in attendance boundaries would follow.

Tampa Bay Times | by Marlene Sokol | February 15, 2021

TAMPA — Hillsborough County public schools with too many empty seats will be eyed for possible mergers or even shut-downs for the year after next, according to the district’s leadership team.

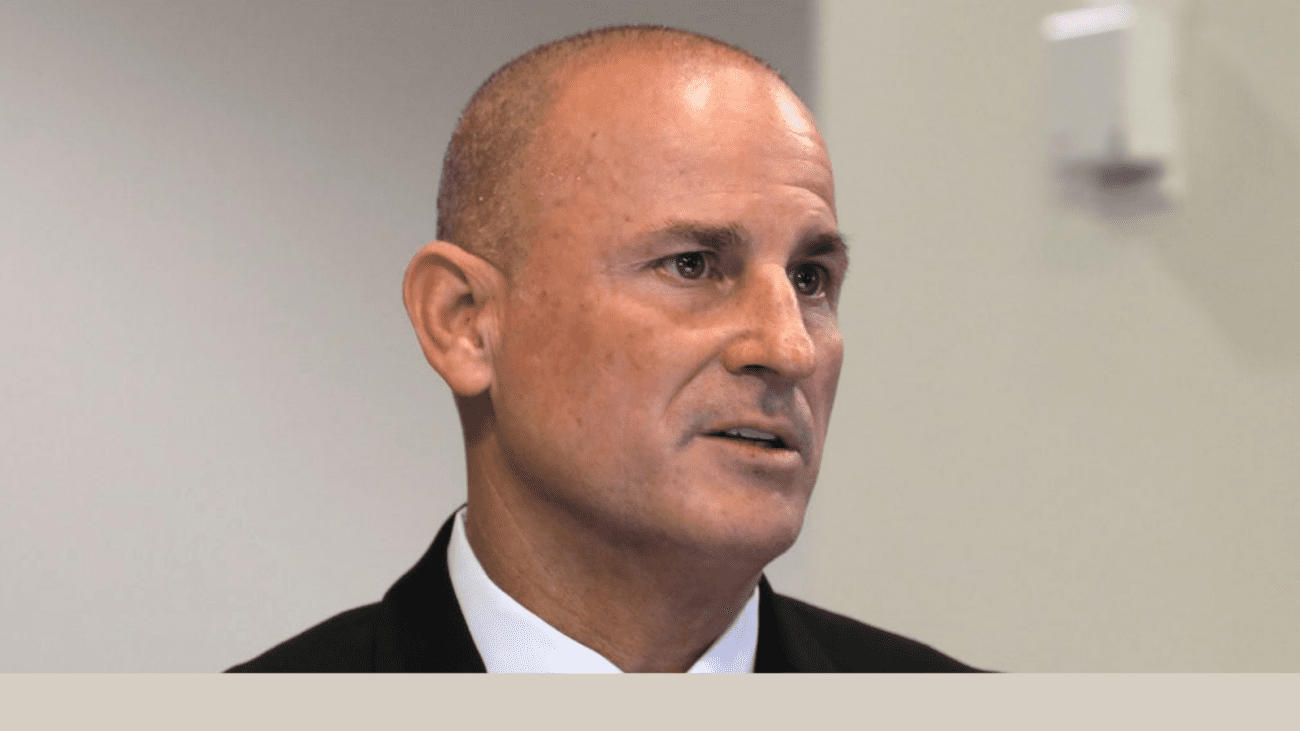

Superintendent Addison Davis and his staff are in the first stages of assessing under-enrolled schools and re-drawing attendance boundaries as part of their effort to stop deficit spending in the district.

Davis said in an interview he is about six weeks away from coming to the School Board with a menu of options. He said he has identified 60 schools that are at least 30 percent vacant.

“We can’t keep the lights on, and maintain operations and instructional materials, and put all the resources in a school when you only have 200-plus students,” Davis said.

Enrollment declines at individual schools happen for a number of reasons, from changing population patterns to the growing popularity of alternatives to government-run public schools.

More than 30,000 of Hillsborough’s public school students attend charters, which are funded through the state but operate independently. Thousands more attend private schools through tax-funded scholarships, and these numbers could grow even more with proposals in the Legislature to expand these programs.

Many schools that are losing enrollment are in Tampa’s urban core, setting up difficult conversations about culture and tradition.

But some are in the suburbs. Smith Middle School in Citrus Park, for example, is at 54 percent capacity with stiff competition from the Henderson Hammock, SLAM and Victory charter schools.

Closing a school is never a pleasant prospect, and such decisions have met with strong community opposition elsewhere in the nation.

Hillsborough has been slow to take such measures. Parents complained when Cahoon Elementary, a popular magnet school in north Tampa, was merged in 2018 with the long-struggling Van Buren Middle to form what is now the Dr. Carter G. Woodson K-8 Leadership Academy. There was less outcry when USF-Patel, a charter school later taken over by the district, was folded into what is now Pizzo K-8.

Davis and deputy superintendent Michael Kemp said it will take about a year to work through the redistricting and consolidation process before implementation. “This is going to take community outreach, community engagement,” Davis said. “It’s going to take thoughtful plans and we’re going to have to be surgeons.”

Stephanie Baxter-Jenkins, executive director of the Hillsboroughteacher’s union, agreed that such decisions must be made with extreme care.

“We think of schools as the center of the community, and it can be very hard on communities when schools close,” she said. “Across the country, we have also seen that school closings disproportionately impact low-resourced communities and communities of color. So we need to be very careful about the choices we make.”

Baxter-Jenkins also said the district is not without blame where the exodus to charter schools is concerned.

“The charter people are good at being efficient,” she said. “They don’t spend their time where they’re not welcome. The bottom line is, if you’re not rolling out the red carpet, you will not necessarily have much of an issue.”

Reconfiguring school attendance is one of many changes district leaders have outlined to build their cash reserves and avoid becoming vulnerable to a state takeover.

More immediately, Davis and his team plan to reduce between 1,500 and 2,000 jobs for the coming school year, continuing a process they slowed down this past year because of resistance from teachers, parents and some members of the School Board.

They are looking for ways to either raise or save $100 million by May or June, when they could otherwise run out of money. But they will not see savings from the coming year’s staff cuts until well after that.

They had hoped for a large infusion of COVID-19 relief from the federal government, which is expected to release more than $200 million for Hillsborough under the CARES Act.

But Kemp and Davis warned that the CARES money comes with numerous complications. It might be delayed as it passes through the state government. It will be shared with charter and private schools.

In a letter last week to superintendents, Florida House Speaker Chris Sprowls cautioned against using the money to fund ongoing operations. And, even more worrisome, there is a chance the state could reduce its own per-pupil allocations as it will consider the CARES money to be a windfall for districts.

In October, Hillsborough ran short on cash and took out a $75 million tax anticipation note, which is a type of bridge loan, to cover payroll. In January Moody’s Investor Service, a major bond-rating firm, issued a downgrade on some of Hillsborough’s debt and maintained its negative outlook of the district.

“Our credit is not favorable,” Kemp said. So if the district has to take out another short-term loan, “it’s going to be extremely expensive.”

Davis said he is exploring a number of options, including changes to the district’s agreement with an operational efficiency contractor. Instead of receiving proceeds of the savings over time, the district would receive the money upfront.

Davis and Kemp, who both arrived from Clay County in 2020, have said for months that the district’s staffing practices caused the imbalance that now threatens its fiscal health and autonomy. Staffing formulas existed but were not followed, they said. Grant-funded positions remained on the books, long after the grants expired.

Some of these positions are in magnet schools that are also getting a hard look. The transportation system for the magnets alone adds millions to a busing system that already is under-funded by the state. Magnet programs also carry additional positions for assistant principals, counselors and lead teachers.

“We can do anything as a district,” Kemp said. “We just can’t do everything, everywhere.”

Davis insisted he is committed to protecting the autonomy of the district and its more than 200 schools.

“I’ve always been about choice for parents,” he said. “But I’m about protecting the organizations in which I’ve worked. My job is to protect public education. And in public education, that’s our district-managed schools. The ones where we control the finances, we control the curriculum, the hires, the implementations, the robust programs.”

He added that “in my conversations with the Department of Education, they don’t want anything to do with taking over the district. They have too much on their plates.”

Photo: Hillsborough County school superintendent Addison Davis and his staff are taking a close look at under-enrolled schools with an eye toward merging or closing some of them. The move is necessary, they say, as the district continues to face financial problems. [ SCOTT KEELER | Times ]