“I Can’t Teach Like This”: Florida’s Education Brain Drain Is Hitting Public Schools Hard

Vanity Fair | By Caleb Ecarma | May 22, 2023

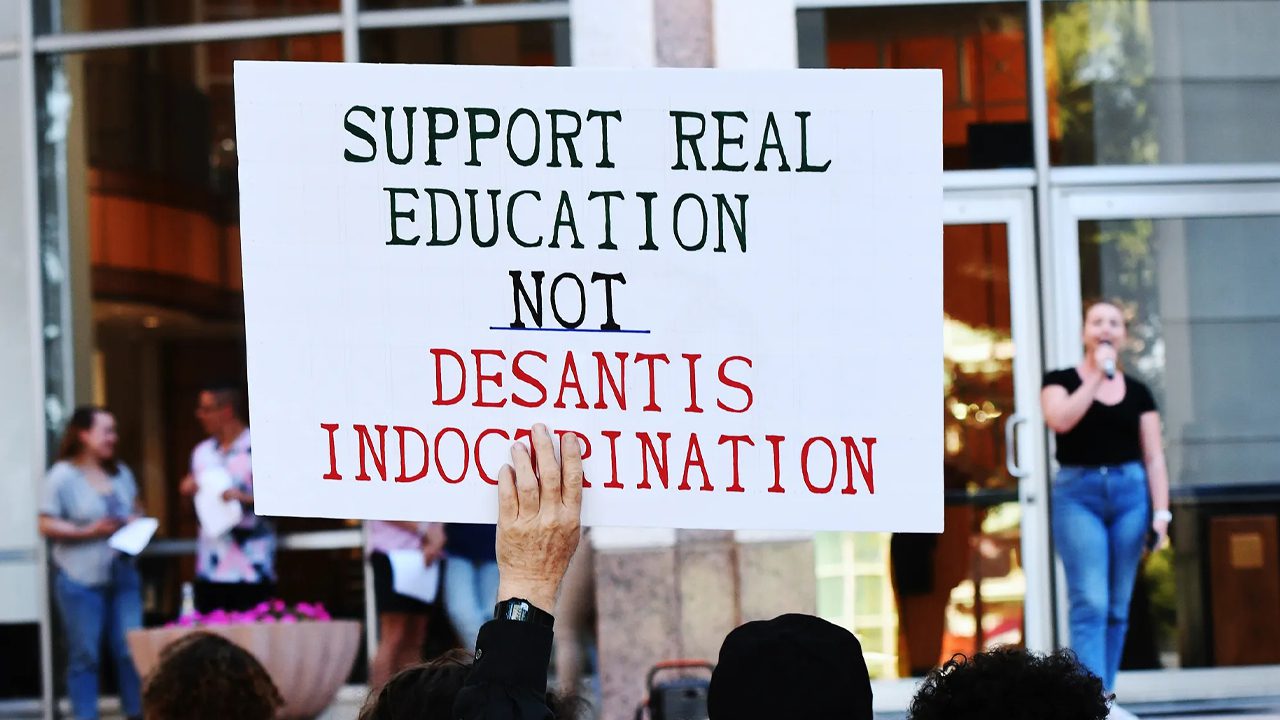

Ron DeSantis’s war on “wokeness” has thrust educators into a legal minefield, pushing many to leave the profession entirely. One union leader says it’s all part of a GOP agenda to eradicate public schools: “This is just a part of their playbook.”

At a signing ceremony last week in Sarasota, where he added three new bills to his culture war belt, Ron DeSantis stood behind a podium emblazoned with a slogan that hailed Florida as “the education state.” It’s this image that he and his fellow Republicans have tirelessly sought to build with a yearslong, multipronged effort to expunge “woke indoctrination” from the state’s public school system.

And yet, ask those on the ground, and that image couldn’t be further from the truth. As Florida’s culture war rages on, educators across the state—which, according to the National Education Association, ranks 48th nationally in average teacher salary—are leaving in droves, with some even retiring early. In January 2019, when DeSantis first took office, Florida had 2,217 teacher vacancies. That number has since more than doubled to 5,294 vacancies as of January 2023, according to the Florida Education Association.

“For the first time, I’ve actually started talking to my investment guy about retirement,” Michael Woods, a teacher who has spent decades working in exceptional-student education for public schools in South Florida, tells me. “I’m a 30-year veteran who showed up every day, hardly calls in sick, but now I don’t want to be a teacher in Florida.” Most troubling to Woods—a gay man who teaches science and biology courses—is the ballooning list of laws that police classroom material, discriminate against LGBTQ+ educators and students, and restrict sex education. “They’re all so vague,” he says of DeSantis’s new laws. “Even things that used to be easy like human reproduction [for ninth graders], I now have to check with my co-teacher and ask, ‘Is this okay? Are we still allowed to teach this?’”

On Wednesday, the governor rubber-stamped a batch of four bills restricting LGBTQ+ rights and expanding the Parental Rights in Education Act—or, as critics have dubbed it, the “Don’t Say Gay” law. The new measures, which will be enforced at public and charter schools, ban educators from discussing sexual orientation or gender identity in pre-K through eighth grade, and place new, vague restrictions on sex education, including that such instructions “be age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.”

This latest salvo was a bridge too far for many teachers, according to Rebecca Pringle, the president of the National Education Association, the largest labor union in the US. “I just talked to one teacher yesterday who is leaving and she said, ‘I can’t teach like this,’” Pringle tells me. “‘I can’t teach while worrying that they’re coming after my license, or I’m committing a felony.’ They’re leaving in protest.” Pringle says she has tried to convince teachers to stay in Florida, given the dearth of teachers in the state. But that discussion has been difficult to have, she says, with teachers who are facing death threats or harassment.

Case in point: One fifth-grade teacher in West Florida said this month that she was placed under investigation by the Florida Department of Education for showing her class Disney’s Strange World, a children’s movie that features an openly gay character. Jenna Barbee, the teacher at hand, said she played the film to give students a post-exam “brain break.” But when a local school board member learned of the showing, Barbee said, she was reported to state officials. Barbee told CNN that she had already submitted her resignation before the incident, in protest of the “politics and the fear of not being able to be who you are” in Florida public schools.

It appears that no educator has yet been prosecuted or charged under Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law or its legislation restricting books in schools. But as fears mount over their future implementation, parents are already witnessing the effects of shorthanded schools and overcrowded classrooms. “Last year, I saw several teachers leave, and we had substitutes for three, four months of the year,” says Reagan Miller, a parent in West Florida whose two children attend public school. “We had a teacher who taught advanced math at our middle school for years and years—he just left to go be a 911 operator,” she tells me, “which blows my mind, that becoming a 911 operator would be less stressful than being a teacher.”

In her work for the Florida Freedom to Read Project—a group combating the right-wing effort to ban books in classrooms and school libraries—Miller says she has directly spoken with a teacher who, upon discovering a banned book in their classroom library, suddenly worried they could face third-degree felony penalties. Under HB 1467, a bill that DeSantis signed into law last year, books provided to students must be selected by a school district employee who has been certified as a media specialist.

There are alternative options for parents concerned by the state’s spiraling public education system, but they are limited and inaccessible to most. “I actually visited a private school that I would consider more progressive—it’s the one choice nearby, but it can only take 40 students and has 186 on the waitlist,” says Miller. “Plus, we already have public schools…and I don’t mind my kids hearing someone else’s point of view.”

As Florida reels from one of the worst teacher-vacancy crises in the country, DeSantis has also moved to dismantle the unions that defend them. Last week, the governor signed into law Senate Bill 256, barring most public sector unions—excluding police unions, of course—from receiving dues directly from workers’ paychecks. Included in the bill is the requirement that non-police unions maintain a membership rate of at least 60% of eligible employees or risk losing their certification.

This two-pronged attack against educators and their union advocates, argues Pringle, the NEA president, is part of an overarching plot to make public schools more and more dysfunctional—therefore eroding community trust in them—before increasingly privatizing the system. “They’re systematically trying to pollute our schools and sow division within the labor movement and within communities,” she says. “This is just a part of their playbook.”