‘I wasn’t thinking about anything except wanting to hurt myself.’ Teen suicide attempts soar

Miami Herald | By Clara-Sophia Daly | October 20, 2022

If you or someone you know is thinking about self harm, call the toll-free National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255). It’s available 24/7.

–

Allison’s quinceañera was nothing like she had dreamt it to be as a child in Costa Rica. She was not at her home surrounded by family. There were no special food or gifts. And she didn’t get to wear the purplish-blue and white chiffon gown she saw herself in.

“I had imagined a princess party with my family!” she said in Spanish. But instead, she spent the day scrambling to find the testing room at Booker T. Washington Senior High School in Miami so she could take her Florida Standards Assessments.

“I was so stressed out that day,” the 11th grader recalled. “It made me depressed.”

That night, she went home to cook dinner for her two younger siblings while her parents were at work. She had to stop herself from cutting her arm with the kitchen knife.

“I was so overwhelmed and wasn’t thinking about anything except wanting to hurt myself,” said Allison, who has considered ending her life on more than one occasion. She considered telling a friend, but that friend had a history of cutting her arms and legs, so she kept it to herself.

JUMPING OFF SCHOOL BUILDINGS

Allison is one of scores of students in South Florida struggling with mental health challenges, exacerbated by the pandemic’s disruption of their school routine. In recent weeks, students have jumped from buildings at two South Florida high schools. The first, a girl at Palmetto High School, survived after jumping from the third floor of a school building within the first week of school. Earlier this month, a senior at Fort Lauderdale High School jumped to his death.

Yet the Miami-Dade school district is not required by state law to keep track of suicides or attempted suicides of students. Instead, the school district tracks the number of risk assessments they complete. The assessment, conducted when students are deemed to be at risk of suicide, determines the level of risk for a student expressing suicidal thoughts or intent to commit suicide. Allison was never assessed for suicide, and her suicidal thoughts were never reported.

Adolescent and child mental health has been declared a national state of emergency by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the Children’s Hospital Association, as of last fall. And in 2020, among Americans ages 10-14 and 25-34, suicide was the second-leading cause of death, followed by unintentional injuries like car crashes or accidental overdose.

“We have to ask people about their mental health routinely like any other vital sign, or we will not do our job in preventing the suicide crisis,” said Kelly Posner Gerstenhaber, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University and the lead scientist of the Columbia Protocol, the most widely used suicide assessment tool.

SUICIDES IN FLORIDA SOAR AMONG YOUNG PEOPLE

While U.S. suicide rates have surged 30 percent among all ages in the last two decades, death rates took a dip during the pandemic because people spent more time with their friends and family. But visits to emergency rooms for suicide attempts, in addition to hospitalizations of people who had attempted suicide, got worse — especially among adolescents.

Nationally, ER visits for mental health crises among those 12 to 17 years old jumped 31 percent between 2019 and 2020, the first year of the coronavirus pandemic, according to researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And for teenage girls, emergency department visits for attempted suicide were higher during the pandemic than in 2019.

During the pandemic, many students reported intense feelings of anxiety, depression, and loneliness — spurred by a lack of social interaction and routine, among other factors.

Florida has witnessed similar trends.

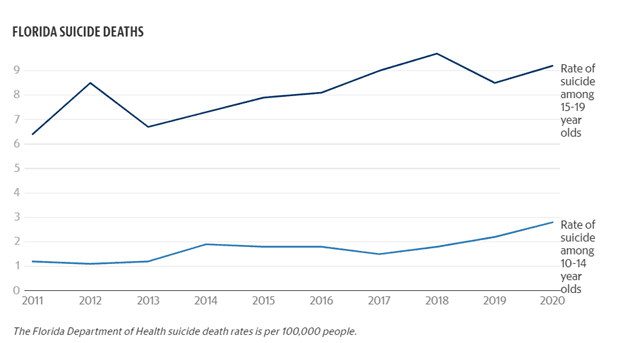

Between 2011 and 2020, suicide rates in Florida have more than doubled among 10- to 14-year-olds. Among 15- to 19-year-olds, deaths by suicide have jumped by more than 40 percent for the same time period, according to the Florida Department of Health.

For attempted suicides, the rate of hospitalizations among 12- to 18-year-olds increased 55 percent during the same period, according to the health department, although the rate has plateaued in recent years.

The majority of people who are hospitalized for suicide attempts, however, are not initially admitted for mental health issues, according to Posner Gerstenhaber. And most suicide attempts occur at home and are not necessarily reported. Thus, their numbers are vastly underrepresented, according to mental health experts.

“We very much believe that the numbers of suicide deaths and suicide attempts are underestimates because of the shame and the stigma and the silence that surrounds this and has been there for generations,” said Posner Gerstenhaber, the Columbia professor of psychiatry.

Posner Gerstenhaber and other mental health experts say suicide prevention assessments should be as widespread as testing for any other vital sign like blood pressure. Otherwise, people will suffer in silence.

STOPPED HERSELF FROM CUTTING

Jasmyn, a 17-year-old senior at Miami Senior High, says she has considered attempting suicide three times.

The Herald is identifying the students only by their first names.

She has been struggling with self-esteem issues and mental illness since middle school. In August, after a long shift at Panera Bread, Jasmyn messaged her girlfriend Jaiden late at night saying she was going to hurt herself. Jasmyn went into the kitchen, grabbed a knife, and placed it on her ankle to begin cutting.

But she stopped herself.

“I’m glad I’m here, but I’m mad I’m trying,” she said after school the next day while eating french fries at Burger King. The fries were her first meal of the day.

Not once has she received professional support or reported her suicidal thoughts. She has not told her mother, grandmother, or aunt about her mental health struggles.

AFRAID TO TALK TO COUNSELORS

Among the 19 students attending Miami-Dade public high schools who spoke to the Herald, the majority say they do not feel comfortable reaching out to counselors. Some believe counselors will tell their parents, while others think the counselors are too busy with schedule changes and other issues.

Destiny, a 15-year-old student at Booker T. Washington High, said of school counselors: “If I tell them my business, they’re gonna snitch.”

Neither Jasmyn nor Allison reported their suicidal thoughts to a school official.

Though the school district does assess students at risk, district officials do not track the outcomes of the risk assessments. They only track how many of the assessments required intervention. In the 2021-2022 school year, 637 risk assessments were deemed serious enough to warrant an intervention of additional counseling and support across the district’s 80 high schools.

“The school district has an incredible amount of systems in place so that it doesn’t get [to the point of the risk assessment],” said a district spokesperson.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGISTS IN SHORT SUPPLY

In the current school year, there are 329,337 students enrolled across Miami-Dade County public schools. There are 188 school psychologists. That means 1 psychologist per roughly 1,750 students.

Posner Gerstenhaber, the lead scientist of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale that the district uses, says that although what the district is doing is good, “They have to get much more upstream. We’ve got to get it much earlier.”

She said the suicide risk assessment should be routine screening for all high school students.

PANDEMIC EXACERBATED MENTAL ILLNESS

Allison, the Booker T. Washington student who did not celebrate her 15th birthday, came to Miami from Costa Rica during the pandemic. She was stuck at home caring for her 6- and 2-year-old siblings while her parents worked long hours. Caring for her siblings, especially the toddler, made it difficult to focus on remote learning. She gave up.

“It made me depressed; my grades would not level up,” she said, noting she had no friends and could not speak any English.

Since 1990, the CDC has conducted a survey across high schools all over the nation. The confidential questionnaire asks students mental health, suicide, sexual orientation and gender identity, among other topics.

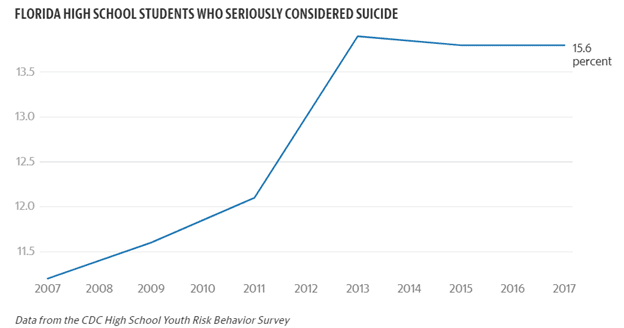

In March, the Florida Department of Education withdrew from the 32-year CDC study — even though about 18 percent of Florida students seriously considered attempting suicide in the past 12 months, according to results from the 2021 CDC survey of over 4,600 high school students in the state.

Between 2007 and 2019, the number of Florida high school students who said they seriously considered attempting suicide increased by 39 percent, according to the CDC questionnaire.

The Florida Department of Education will administer its own survey in 2023 “for enhanced alignment within Florida’s mental health instruction,” according to Florida Department of Health officials.

But some healthcare professionals say Florida’s decision to leave this study underscores a larger issue in the state in terms of providing the data that school districts, healthcare providers, and policymakers need to inform decisions, especially for communities at higher risk.

LGBTQ, BLACK STUDENTS AT HIGHER RISK

LGBTQ and Black students are at increased risk of depression, anxiety and suicide, health data show. Nationally, 9 percent of high school students reported attempting suicide in the past year, according to the CDC. For LGBTQ people, that rate was 23 percent.

In 2020, for the first time in U.S. history, Black children under 18 were two times more likely to die by suicide than white children under 18, according to the CDC.

“It is a disservice to not allow us to understand the representation of these groups. Without data about diverse groups, we can’t create policy or have effective care,” said Natasha Poulopoulos, a pediatric psychologist in South Florida.

Aside from school stress and money problems at home, one of the things that weighed on Jasmyn’s mind when she thought about ending her own life was feeling like she could never truly be the girl she wants to be.

“I know this has happened to a lot of other trans people,” she said. The Miami High senior began transitioning four months ago, after spending most of her junior year researching how to do so.

She gets along well with her family but doesn’t open up much to them. They do not know that she loves listening to Polish rap, that she likes vintage stuff, or that she takes hormones to help her transition from male to female. “They still think I’m into sh*t I liked like 100 years ago!” Jasmyn exclaimed.

THERAPY, MEDICATION ARE KEY

Mental health experts say that one of the best ways to prevent suicide is for everyone in a community — from parents to teachers, to coaches and classmates — to be open to talking about people’s emotional health struggles. Moreover, they note, the best treatments for preventing suicide are therapy and medication.

Shayla, 15, a sophomore at Coral Gables Senior High School, attempted to overdose on pills while she was home alone at her grandmother’s house during the fall of 2021. Eventually, she went to the school counselor. She said she asked the counselor not to tell her parents and that the counselor made her feel comfortable opening up. Soon after, the counselor called her mom, who admitted her into the hospital.

The Miami-Dade school district says they are mandated to notify parents when there is a change related to a student’s mental, emotional, or physical health or well-being. This is in accordance with the new Parental Rights in Education bill, which Gov. DeSantis signed into law earlier this year and went into effect in July. Critics have dubbed it the ‘Don’t say gay’ bill.

While in the hospital, Shayla said her mom would call and make jokes over the phone, saying things like, “You are doing it for attention.” Even thinking about it now makes her upset.

During this period, she said everything was spiraling out of control. She cried a lot, would cut herself, and lost the will to live.

Now, she is being treated for depression and has the support of a cousin her age who has gone through similar mental health struggles.

FINDING HELP CAN BE TOUGH

But Jasmyn, the student at Miami Senior High who almost cut herself with a knife, cannot afford a therapist. Nor can many other young people.

“Wait lists have exponentially grown and people are unable to access mental health services. That is why we may see more mental health crises because we are intervening as opposed to preventing,” said Poulopoulos, the pediatric psychologist.

Poulopoulos says the majority of patients she sees in the hospital for mental health problems have difficulty finding a provider after they are discharged. Especially for patients on Medicaid, the federal health insurance program for people with low incomes, the wait to find a therapist can be nine months to a year.

Dr. Elizabeth Pulgaron is an associate professor of clinical pediatrics and the director of mental health services for the school health initiative at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. She said she’d like to get to a place where she could focus on preventive mental health work, instead of having to put out fires.

As a licensed psychologist who supervises nine Miami-Dade public schools involved in the UM initiative, her cellphone rings at least once a week because of a mental health crisis or suicide attempt at a school, she said.

There is no across-the-board mental health screening at high schools, said Pulgaron, who runs grant-funded mental health programs at nine schools.

If the district implements a mental health screening for all high school students, they would have a legal and moral obligation to provide sufficient care to those students. Pulgaron says school officials avoid asking all students about ending their life because of this liability.

MIAMI-DADE STUDENTS’ ISSUES

The preliminary data Pulgaron collected in her clinics from 2019 and 2020 reveal that about 10 percent of students identified themselves as having elevated mental health scores above a clinical cutoff. In other words, 1 in 10 students she saw in her school clinics during this period were struggling with mental health issues far beyond having a bad day.

Once, a student came to the clinic to see Pulgaron because an assistant principal had noticed she was looking sad, disheveled and depressed.

She came into the clinic with a mask on, her eyes peering down toward the floor. She had arrived from a South American country just a few weeks before the pandemic began, and was thrust into remote learning. Once school went back to being in-person, she didn’t have any friends.

As she sat in the exam room, Pulgaron asked: “When is the last time you cut, and what do you normally cut with?”

The student said she normally cuts with a razor. She explained that her father, with whom she lives, doesn’t know that she cuts.

Pulgaron asked: “When was the last time you cut?”

The student: “Oh, well, yesterday.”

Pulgaron: “Well, do you have the razor with you?”

The student opened up her book bag and brought out the razor. After a discussion, they disposed of the razor and made a safety plan. Pulgaron contacted the student’s parents and the student started seeing a therapist, whom she now sees regularly.

But only three high schools across the 64 high schools in the Miami-Dade school system have clinics such as this one. Pulgaron’s other six clinics are in middle and elementary schools.

Pulgaron said one therapist had a student who was dealing with mental health issues and asked to speak to a “trust counselor.” When the student went to the office and knocked on their door, she was told the counselor was not at school that day and needed to come back on Tuesday.

“It takes a lot of courage to seek help,’ she said. “So if the provider or that person who’s supposed to be your safety, be your resource, be your guide, well, she’s only there on Tuesdays, so we need to save all of our problems for Tuesdays. You know, we can do better than that.”

LISTENING WITH AN EMPATHETIC EAR

Experts agree that being available to others is one of the best ways to prevent suicides. Saying things such as “I am willing to listen,” and “How are you, really?” can be the difference between life and death.

“Some stories are complicated. If we can step back and not judge each other and listen with an empathetic ear, that is what is well received,” Pulgaron said.

But finding an empathetic ear can be difficult. Many district mental health counselors travel to five different schools in a given week. And there’s a dearth of Spanish-speaking providers.

Allison is now halfway through her junior year at Booker T. Washington and is happy to be making friends and working on her English language skills. She enjoys her art courses and dreams of someday becoming a singer and releasing her own songs.

“But if I can’t, I’ll make the decision to study nursing,” she said.

She hopes to find a therapist to speak to about her struggles.