Inside Hillsborough’s D and F schools: Turnover, shortages, calls for help

How a one-year hiccup in Florida’s school grading system unmasked glaring disparities in the classroom.

Tampa Bay Times | By Marlene Sokol and Ian Hodgson | May 2, 2024

Each day, 18,000 students take their seats inside Hillsborough County’s most struggling schools, enough to fill a small city.

The county by far logged more schools with D or F grades than any other in Florida, according to state numbers released in December. In all, 33 elementary and middle schools.

The vast majority of students in those schools come from poor families, with stresses at home that can hamper their ability to learn.

They are kids who need the most from their school district. Yet they are more likely to be greeted in class by a substitute teacher, or one with far less experience than those at higher-performing schools, a Tampa Bay Times analysis found.

In an average week, they will witness more fights or acts of defiance or bullying. There’s a good chance they’ll see more turnover in their principal’s office. And the staff will suffer lower morale.

With each year, the problem grows more concentrated. State and district policies give families more freedom than ever to choose other schools, leaving poorer families behind. Hillsborough already is one of the state’s most-segregated districts by race and income.

Florida awarded its 2023 letter grades based on student scores alone because new state tests and standards meant there was no way to compare results with the prior year. Gone was the extra credit Florida schools normally get when students show improvement — a one-year hiccup that unmasked some hard truths for the nation’s seventh-largest school district.

The Times reviewed hundreds of pages of school district documents and school surveys. Reporters analyzed state and federal datasets, spoke to more than 20 educators and experts, and visited an F-graded school in Tampa for a closer look.

Almost half the children across D and F schools were woefully behind in reading, the Times analysis found.

Two Tampa schools had the lowest pass rates on reading in the state. One of them, Just Elementary, is now closed, with three more shutting down in June.Of the 20 worst-performing elementary schools on the reading test, almost half were in Hillsborough County.

Those and other numbers present a daunting challenge for the school board and new Superintendent Van Ayres, the district’s fourth top leader in nine years. A board majority, with prodding from Ayres, has approved a property tax referendum that could help by shoring up the teaching force. But some critics argue the district can’t be counted on to spend that money effectively.

Florida’s other school districts serve kids in poverty, too, some much larger than Hillsborough. They operate with the same big problems, the same rules for school grades.

Yet it’s Hillsborough that struggles the most.

Palm Beach County came closest with 23 D and F schools. The state’s largest district, Miami-Dade, had five.

Eight of Florida’s 10 largest districts saw either a decrease in D and F schools or a small increase from the year before.

The number in Hillsborough more than doubled.

Short on experience

It takes four years for a teacher to become “experienced” under Florida guidelines, and Hillsborough as a whole has a larger share of those teachers than the state average.

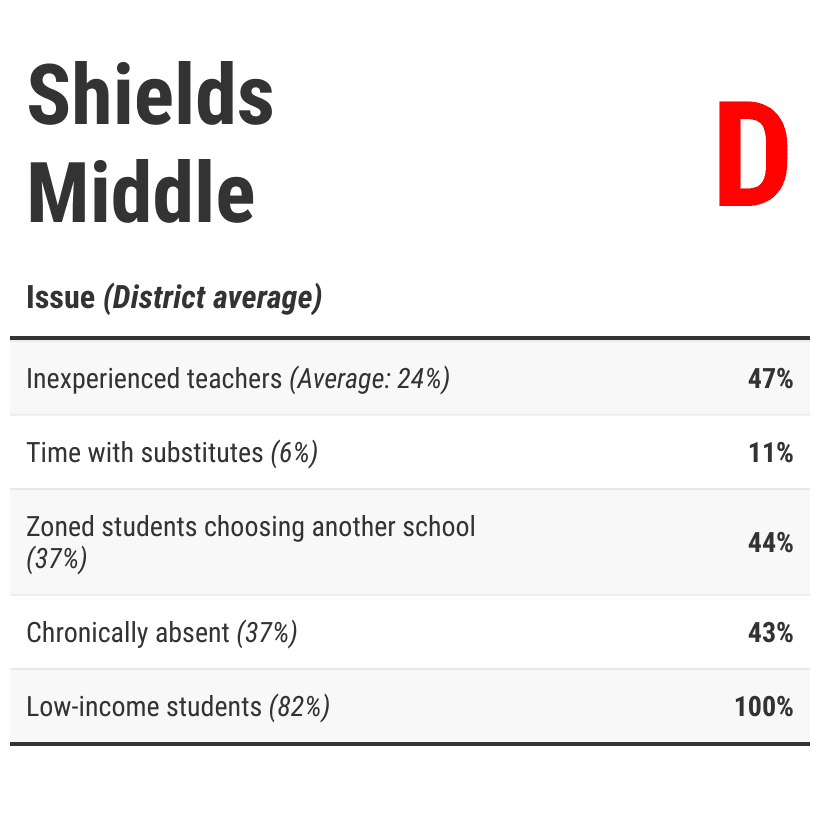

But that’s not the case at the county’sD and F schools. A third of their teachers are inexperienced on average, nearly triple the rate at itsA-graded schools.

Experience and formal training make a world of difference, said veteran teacher Christie Gold, who oversees college interns with the school district’s human resources department. New teachers must know about child development, teaching strategies and how tomanagea fullclassroom.

When someone without a teaching background is assigned to a high-needs school, “it’s a steep hill to climb,” Gold said. “I don’t think it’s an ideal situation for someone who just woke up and said, ‘I really want to be a teacher.’”

At Monroe Middle Magnet, a D-graded schoola few miles from MacDill Air Force Base, half of its 26 teachers had fewer than four years’ experience last year.About two-thirds were new to the school, according to payroll data.

Inexperience characterized the teaching ranks at D-gradedIppolito Elementary in Riverview. Administrators wrote in their annual report that the school’s low scores were “a direct result of a large percentage of teachers new to the profession, country, state and/or content.”

Six other schools described similar conditions.

In anonymous district surveys, teachers and parents also cited inexperience and turnover.

“We need more staff; we have many vacancies,” wrote a teacher at Adams Middle.

“The turnover of staff at this school is sad,” said a parent at Eisenhower Middle.

At Tampa’s Sheehy Elementary, three teachers in one grade left the district last year. The impact was severe at a school of just 347 students. Passing rates in that grade were 16% in reading and math.

Schoolwide, 20% of students passed in both subjects — among the lowest rates in Florida.

Steady teaching was hard to find in other grades, too. At one point, a vacancy forced Sheehy’s longtime principal, Delia Gadson-Yarbrough, to teach fifth grade English for several weeks.

Sheehy wound up with an F.

Teacher stability is linked to student performance, according to five years of payroll data examined by the Times.

Roughly one-third of teachers at D and F schools were in their first year at the school, according to payroll data. By comparison, at A schools, a quarter were teaching there for the first time.

At the D and F schools last year, a majority of teachers had been there less than three years. By comparison, at A schools, only 1 in 3 were.

Another feature of the low-scoring schools was an outsize share of regular teachers who lacked training.

Students were almost twice as likely as their A-school peers to have a teacher missing a state credential for their grade or course, according to nearly 1,200 notices shared with the school board last year. More than half of the notices were for teachers with students still learning English.

Students at the D and F schools alsowere twice as likely to have a teacher who arrived at the school from another profession and was still in training.

And they were more than twice as likely to have a teacher rated “unsatisfactory” or “needs improvement,” according to data from the 2021-22 school year.

“Our children who need those qualified teachers the most — we don’t have them,” Colleen Faucett, the district’s chief academic officer, told the school board recently.

Turnover among principals didn’t help.

While schools typically change leaders once or twice in a decade, 25 of the D and F schools had two or more principals in the last seven years.

Robles Elementary in East Tampa had five principals during that period, plus high teacher turnover to go with it. The school lost nearly 40% of its teachers every year, on average, between 2019 and 2022, payroll records show. That’s almost double the rate at the district’s A schools, according to a Times analysis.

The churn of teachers and administrators leads to a “vicious cycle” that exacerbates existing disparities in education, said Aaron Pallas, a professor at Columbia University’s Teachers College.

Stress caused by behavior problems and poor performance pushes out experienced educators. And that instability can make behavior issues worse.

“Stability is good for schools, period,” Pallas said. And schools that don’t have it “are almost always likely to struggle.”

The role of substitutes

Eric Kirylo was assigned to Witter Elementary in Tampa as a special education teacher in August 2022. His job was to work in small groups with students needing extra help.

That year at Witter, fiveteachers and an assistant principal left the district, personnel records show.

To fill the gaps, the school called on substitute teachers.

“The subs were playing movies all day,” said Kirylo, who left the district in February amid a district investigation after he clashed with another teacher. He now teaches high school in Iowa.

“I would try to pull the kids out and they would say, ‘But we’re watching the movie,’” Kirylo recalled. “Kids were standing up and getting in the sub’s face. The sub would say, ‘Have a seat,’ and they would say, ‘No, you sit down.’”

Another school, Foster Elementary, cited “teacher turnover throughout the school year” in its annual report to the state. So, Foster relied on “long-term substitutes with limited and varying levels of teaching experience and expertise,” the report said.

Hillsborough’s D and F schools called in substitute teachers twice as often as A schools during the 2022-23 academic year, according to a Times analysis of substitute shifts per student. The numbers were based on invoices from Kelly Education, a staffing firm that supplies subs for the district.

The district requires only a high school diploma or equivalent to work as a substitute — the minimum qualification under state law. Substitutes are required to complete four training segments before they can be placed in a classroom.

The district relies on long-term substitutes to fill vacancies and as a way to recruit qualified teachers into the full-time workforce.

Ayres, the superintendent, noted that most of the time substitutes in the D and F schools were in long-term positions and not filling in for teachers who called in sick. The district said it requires its long-term subs to be college-educated, unless there are extenuating circumstances.

Look up Hillsborough County’s D- and F-graded schools

Source: Florida Department of Education; Hillsborough County Public Schools; National Center for Education Statistics

IAN HODGSON and LANGSTON TAYLOR | Tampa Bay Times

Sometimes, instead of a substitute, the remaining teachers are called on to help cover a class.

“We are so understaffed,” a teacher from Witter Elementary wrote in the district’s annual climate survey. “I feel like, even when I am very sick with a fever, I have to come to school because I do not want to inconvenience my co-workers by having them split my class.”

In the same survey, another teacher from Shields Middle lamented the prevalence of substitutes who end up at a school full time, instead of a day or two.

“Our students are not getting the education they deserve,” the teacher wrote. “The students know when someone cares, and our students know that only some of the teachers and administrators care about their education. They’re young but not stupid.”

Behavior: “A daily struggle”

Parnell Cross was one of the teachers who left Hillsborough last year.

After a decadelong teaching career out of state, the district assigned him in the summer of 2022 to Shields Middle in rural south Hillsborough.

Shields had a reputation as a tough place. The year before, it averaged almost one fight a day.

Though the staff had warned Cross that his students had performed below their peers the year before, he was shocked by what he found.

He said in an interview that most students in his seventh grade social studies class were reading at or below a fifth grade level. And he described Shields as a place of “total chaos.”

He’d smell marijuana in the halls every day. Students would hurl profanities at teachers, he said.

Cross left before the end of the school year, returning to Texas for a different career.

“It hurt me, it pained me to leave,” he said. “I developed a relationship with these kids, like most teachers do. I realized there was no winning.”

Other teachers, with and without experience, struggled similarly with student discipline. Some blamed the staff turnover at their schools on behavior issues and the way administrators responded.

Elementary schools that received a D or F reported a fight or physical attack every other week, on average, to the state. Middle schools reported a fight an average of nearly three times a week.

As a group, the D and F schools reported more than seven times the number of violent disruptions than the district’s A schools, adjusting for the number of students in each school.

They also saw incidents such as threats, assault and fighting increase by 49% during a five-year stretch ending last year, even as their student population dropped 13%.

The typical A-graded middle school in Hillsborough reported fewer than two fights or physical attacks a month last year. Eisenhower Middle reported one every day, on average.

In anonymous district surveys, parents described Eisenhower students vaping in the hallways, and eighth graders jumping a younger child in front of witnesses.

Vielka Wint, who taught math at Eisenhower for eight weeks, said, “I was afraid for my life” after a female student confronted her angrily. “She came at my face, was cursing, all the F words and everything.”

At Potter Elementary in East Tampa, second grade teacher DeMonte’ Baker described a litany of daily disruptions, from yelling and fights to children throwing books and furniture. “We were calling parents so much, the parents stopped responding,” he said.

Erik Ahrens began teaching at Lamb Elementary after working in several other fields. He expected some misbehavior, he said, “but it was a daily struggle.”

They would yell, curse and throw things, he said of students. Other times, they’d get up and dance around the room.

Across the D and F schools, conditions like that are a drag on staff morale. In a survey of 6,000 teachers, 58% in those schools agreed that their school was “a good place to teach and learn,” compared to 73% districtwide.

RobKriete, president of the Hillsborough teachers union, said behavior problems everywhere could be helped with better school staffing. Among its many challenges last year, the district was adjusting to austerity measures to balance its budget.

“We’re seeing bigger, larger class sizes than ever, at least in my time doing this job, for sure,” he said. “We don’t have things in place that help with these students when they’re acting out.”

Playing catch-up

Students at Hillsborough’s D and F schools overwhelmingly come from low-income families, which means many arrive with more baggage than their peers — from trauma and low nutrition to lack of exposure to books.

Compared to students at A-rated schools, they are about half as likely to enter kindergarten with proper preparation, according to state assessments that measure basic knowledge, such as letters and numbers.

More than 70% of students at A-graded schools are typically deemed kindergarten-ready, while the rate is sometimes lower than 20% at the D and F schools.

“It’s not unusual to have a child come in and talk about, ‘I couldn’t sleep last night because I heard gunshots,’” said Gadson-Yarbrough, the Sheehy Elementary principal. Escalating rents force some families to double up and, after a dispute, some of them might wind up sleeping in their car.

Nearly 40% of children zoned for Sheehy live below the poverty line, more than double the county average, according to census data.

At the D and F schools, nearly all students qualify for a free lunch, a common measure of poverty. That’s more than double the rate at Hillsborough’s A schools.

The D and F schools also have some of the district’s highest absenteeism, a crucial factor in student success.

James Elementary had the lowest average daily attendance rate in the district, at 84%. Robles and Just elementary schools also were among the 12 worst, along with Adams Middle.

In its report to the state, Adams described itself as “highly transient,” meaning families who send their kids there tend to move frequently.

“On average,” the report said, “our students have attended three middle schools by their 7th grade year.”

Based on their poverty rates, Hillsborough schools typically receive about $75 million annually in federal funding that can be used to pay for tutors, coaches or services to boost student performance.

Hillsborough also offers a $5,000 bonus to teachers at its neediest schools. And the district assigns college teaching interns to those schools, so they get accustomed to the environment early on.

But those efforts have not been enough to keep the schools staffed with experienced teachers. A nationwide teacher shortage has made it harder to hire for any school, much less the struggling ones.

What would it take to move the needle?

“That’s the million-dollar question,” said Ayres, the superintendent, adding that it’s more than just a money issue. Teachers want to feel comfortable with the school setting where they work.

“There are a lot of components,” Ayres said.

Attracting teachers is one of the biggest challenges he faces, he told school board members in February. It’s the reason he’s pushing for a special voter-approved property tax designed to bring Hillsborough in line with Pinellas, Pasco and Orange counties. In those and other Florida districts, the tax pays for higher teacher starting salaries.

Critics of the tax, including some who are running for school board, say the district is not transparent enough with its finances. And some board members pushed back initially, saying Hillsborough residents are already straining from escalating housing costs.

Ayres said he wouldn’t be proposing the tax if the district didn’t urgently need more qualified teachers.

“That is something that keeps me up at night — students in classrooms without a high-quality teacher,” he told board members. “It comes down to day-to-day instruction. When I don’t have that high-quality teacher in place, I get results like this.”

Segregated

While other districts face these problems too, Hillsborough stands out in how its poor students are packed into struggling schools.

Among the 10 largest districts in Florida, Hillsborough’s elementary and middle school zones were the third most economically segregated, according to a Times analysis of state data.

They’re also among the most racially segregated in the state, and Black students are twice as likely to be zoned for a D or F school in Hillsborough.

School choice only exacerbates the problem.

Families zoned to attend the 33 schools are moving in large numbers to magnet schools and an ever-growing number of independently managed charter schools. Or they’re opting for private schools or homeschooling, using the $8,000 state vouchers now available annually to every K-12 student in Florida.

Parents whose children were zoned for a D or F school were almost twice as likely to find another option as those zoned for an A school in 2022.

Asked to explain why their students lagged behind in math last year, administrators at Eisenhower Middle wrote in their annual report to the state: “There are multiple charter schools and district magnet schools that attract our higher achieving students.”

The migration has made Hillsborough’s A-rated schools wealthier and whiter, while the share of low-income and Black students has increased at the district’s lowest-performing schools.

At Eisenhower, for instance, nearly two-thirds of the white students zoned for the school went elsewhere in 2022-23.

At Adams Middle, the population of public middle school students living in the attendance zone was 24% white last year, while actual enrollment at Adams was 7% white. Black and Hispanic students made up 85% of the school’s population.

Adams would be a more diverse school if everyone in the zone went there. The boundary includes the fashionable Original Carrollwood area and lower-income neighborhoods near the University of South Florida.

But many families have shown a strong aversion to attending Adams, as evidenced by a successful campaign to convert Carrollwood Elementary to a K-8 school so kids won’t have to attend their zoned middle school. Today, Adams is so underenrolled that the district plans to close it.

A similar campaign is underway by families in the Eisenhower zone, where more than 1,000 studentsopted for charter schools last year. Kids who remain at Eisenhower feel left behind, said J. Desiree Rodriguez, who worked there as a study skills teacher last year.

“They felt like the district forgot about them,” she said.

Other districts have found ways to avoid the kind of segregation happening in Hillsborough.

Federal law prohibits districts from assigning students to schools based on race or ethnic background. But it does not prohibit them from using income as a basis for drawing school boundaries that encourage diversity.

In Dallas, for example, schools that intentionally mix kids from poor and wealthier families have proven successful, the Hechinger Report found in 2022.

Decades of research indicate that mixing students of different socioeconomic backgrounds helps increase education outcomes and lifetime earnings for poor students.

Educators have sought smaller-scale solutions too.

This year, Hillsborough rolled out extra Saturday classes in reading, math and science at some schools. Sheehy Elementary gave their program a catchy name: Dream Big Academy. Staff members promoted the classes all week. The program seemed to work — on average, the 60 students who took part improved their reading skills.

Hillsborough has multiple programs to support teachers, boost literacy and improve student behavior, said district spokesperson Tanya Arja, who declined the Times’ request to visit more D and F schools besides Sheehy. In an email, she praised “our hard-working principals, teachers and support staff who are doing their absolute best to meet students where they are and give them the resources they need to be successful.”

Midyear test scores for the D and F elementary schools were not promising. They show students at most of those schools falling further behind in reading and math.

Ayres has said he wants all students to meet state expectations. But he also says he takes some comfort in knowing that Florida’s school grading system will return to normal this year, with the added credit for improved student scores.

Why Hillsborough needs the added credit to boost its grades is not clear. The lack of it didn’t have nearly the impact on most other big school systems in Florida. Eight of the state’s 10 largest districts either had fewer D and F schools last year or only a handful more, while in Hillsborough they went from 14 to 33.

Ayres said in December he didn’t know what made Hillsborough an outlier. He speculated that staff in other districts had been better prepared for the state’s new tests.

Asked again in April, he said in an email that he’s looking forward, not backward. He mentioned the district’s new initiative on phonics to improve reading skills, and vowed to expand literacy efforts.

”I am not pleased with the previous outcomes,” he said. “However, from Day 1, our team has been concentrating on providing all students with a great education.”