Many States Omit Climate Education. These Teachers Are Trying to Slip It In.

Around the United States, middle school science standards have minimal references to climate change and teachers on average spend just a few hours a year teaching it.

New York Times | By Winston Choi-Schagrin | November 1, 2022

In mid-October, just two weeks after Hurricane Ian struck her state, Bertha Vazquez asked her class of seventh graders to go online and search for information about climate change. Specifically, she tasked them to find sites that cast doubt on its human causes and who paid for them.

It was a sophisticated exercise for the 12-year-olds, Ms. Vazquez said, teaching them to discern climate facts from a mass of online disinformation. But she also thought it an important capstone to the end of two weeks she dedicates to teaching her Miami students about climate change, possible solutions and the barriers to progress.

“I’m really passionate about this issue,” she said. “I have to find a way to sneak it in.”

That’s because in Florida, where Ms. Vazquez has taught for more than 30 years, and where her students are already seeing the dramatic impacts of a warming planet, the words “climate change” do not appear in the state’s middle or elementary school education standards.

Climate change is set to transform where students can live and what jobs they’ll do as adults. And yet, despite being one of the most important issues for young people, it appears only minimally in many state middle school science standards nationwide. Florida does not include the topic and Texas dedicates three bullet points to climate change in its 27 pages of standards. More than 40 states have adopted standards that include just one explicit reference to climate change.

“Middle school is where these kids are starting to get their moral compass and to back that compass up with logic,” said Michael Padilla, a professor emeritus at Clemson University and a former president of the National Science Teachers Association. “So middle school is a classic opportunity to have more focus on climate change.”

For those who do receive formal instruction on climate change, it will most likely happen in middle school science classrooms. But many middle school standards don’t explicitly mention climate change, so it falls largely on teachers and individual school districts to find ways to integrate it into lessons, often working against the dual hurdles of limited time and inadequate support.

Ms. Vazquez makes the state’s requirement that she teach energy transfer an opportunity to talk about how wind turbines work. The ecology requirement becomes a chance to discuss the consequences of deforestation.

“What if the candlemakers had stopped the light bulb? We should be the leaders in solar and wind. I tell my students, ‘Don’t let the candlemakers stop the light bulb.’”

Bertha Vazquez, seventh grade science teacher, Miami.

By Eva Marie Uzcategui for The New York Times

But her commitment to the subject is not representative of how climate change is taught around the country. Around half of middle school science teachers either don’t cover the subject or spend less than two hours a year on it, according to a survey by the National Center for Science Education.

That’s hardly enough time to teach the essentials, said Glenn Branch, the center’s deputy director. They need to learn, at the very least, the fundamentals of climate science, including the role humans play, the consequences of a changing climate, as well as solutions.

It is clear that people want climate change to be taught. Around 80 percent of American parents think that schools should teach climate change, a sentiment shared by students.

“Kids are demanding more, and wanting more,” said Sarah Ruggiero, a science teacher for the Eugene School District, in Oregon.

Education experts, too, say it is vital that climate change is addressed in a classroom setting. Kids are already learning about it from TV and seeing it in the changing weather around them.

“Students everywhere know it’s a problem,” said Michael Wysession, a professor of earth science at Washington University in St. Louis who has written 30 textbooks and helped write the Next Generation Science Standards, a set of recommendations for science instruction. “The challenge is to keep them from getting depressed about it.”

“One of the things I have students do is find people or corporations or inventions that are making a difference, so they don’t feel defeated. There are so many things out there that people are doing, whether it’s changing your light bulbs at home or you’re getting corporations to change how they do business.”

Ana Driggs, sixth grade teacher in Miami.

By Eva Marie Uzcategui for The New York Times

Over the course of a year, a middle school science class can expect to cover everything from photosynthesis to the electromagnetic spectrum, all in 180 days.

The general topics are dictated by educational standards, the greatest mechanism by which a state can influence what children learn and what teachers spend their time on.

A decade ago, 26 states and several groups representing teachers and scientists unveiled the Next Generation Science Standards. Since then 45 states and the District of Columbia have adopted the standards or similar ones.

But at the middle school level, even the Next Generation standards include only one standard out of about 60 that explicitly mentions climate change. An analysis by researchers at the University of Maryland found that 17 other standards have a connection to climate change, but leave it up to states, school districts and teachers to make those connections in their lessons.

Still, some of the most populous states continue to write their own and a review of those standards found that climate change doesn’t feature as prominently. In some cases, this is because the standards haven’t been updated, Mr. Branch said. States typically review them every 10 years or so, but Florida’s current standards were adopted in 2008.

In other cases, though, climate change’s place in standards is still under debate. Last year, the Texas State Board of Education voted on new science standards. A board member who is also a lawyer for the oil giant Shell succeeded in cutting the requirement that eighth graders learn how to “describe efforts to mitigate climate change.”

Such seemingly minor changes in language are important. They may not make much difference for a teacher who is already invested in teaching about climate change, said Katie Worth, the author of “Miseducation: How Climate Change Is Taught in America.” “But it gives a toehold to those who are inclined to climate skepticism.”

In 2020, the National Center for Science Education and the Texas Freedom Network released a report that graded states on how their standards addressed climate change. Half the states earned a B+ while 10 states, including Florida and Texas, got a D or worse.

A curriculum doesn’t exist until it enters the classroom. And since so many of the middle school Next Generation Science Standards have connections to climate change but don’t explicitly mention them, it can be a major opportunity for teachers.

But researchers have found that many teachers received little climate education themselves.

“The most crucial intervention that we have to make progress on is professional support for teachers,” said Frank Niepold, the senior climate education program manager at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. But he warns that this might be the hardest piece of the puzzle to solve.

Some states, including Washington, California, and Maine are turning to teacher training programs.

National science educators have lauded ClimeTime as one of the best efforts. The program receives several million dollars a year in state funding. Since 2018, it has trained 14,000 teachers, or more than a fifth of the teachers in Washington State.

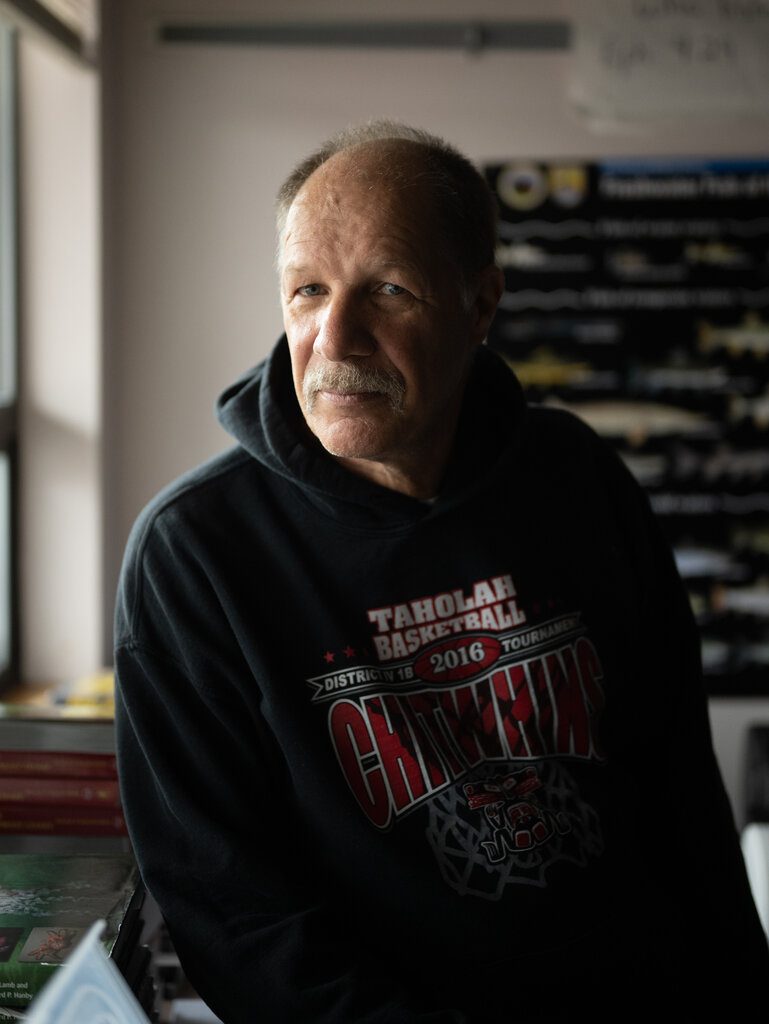

“I tell them, ‘This is your responsibility to your community. You are supposed to leave the land, if not the same, then better than it was for your grandchildren. They buy into it and they love it.’”

Jerry Walther, teacher at Taholah School on the Quinault Indian Nation

Chona Kasinger for The New York Times

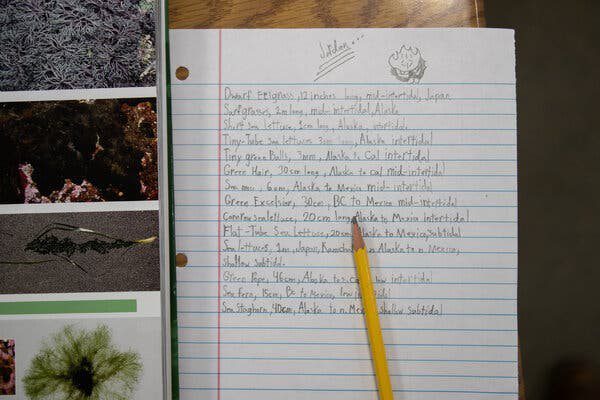

When Jerry Walther, a natural resources teacher in Taholah, on the Quinault Indian Nation, trains other teachers about how he teaches climate change, he tells them how he regularly takes his students outside. “Each community has its own climate and culture,” he said. “And that culture is interesting to its students.”

When his students look at the ocean and rivers, the class inevitably begins talking about climate change, about how the water is warming and harmful algal blooms they’ve all witnessed, he said. “For three years we haven’t been able to fish sockeye. How is it affecting our way of life, and how can we ourselves try to change it?”

According to teachers, one of the main challenges is a lack of good supplemental materials.

Brianna Escobar, a sixth grade science teacher in Garland, Texas, uses textbooks that were published in 2015, which are based on standards that are more than a decade old.

“There are kids, I’m sure, whose families are in oil. So I try to frame things as a question. For instance, I ask: After comparing the types of energy resources we use in Texas, which do you think are better for the environment or people? … And they normally come to these ideas by themselves.”

Brianna Escobar, a sixth grade science teacher in Garland, Texas

Cooper Neill for The New York Times

So it is unsurprising that teachers turn to online materials. But the information they find there may be outdated, inaccurate or simply not suitable for children. The Climate Literacy and Energy Awareness Network, an organization that provides free climate education materials, found that only 700 of the 30,000 free online materials they reviewed were accurate and suitable for use in schools.

In the world beyond classrooms, thinking about climate change involves much more than merely understanding climate science and the greenhouse effect. It’s about changing our energy systems and preparing for waves of climate migration. It’s also about solutions, coming up with policies to adapt to extreme weather events and decarbonize large parts of our economy.

Which is why climate education is now expanding into areas like the arts and humanities, and social studies. Beginning this year, New Jersey is incorporating some aspect of climate change’s effects, as well as solutions, into its standards for every grade band and in every subject area. National organizations representing English and social studies teachers have called for greater engagement with climate change in their classes.

These developments are a heartening and necessary step forward, Ms. Vazquez said. Teaching about climate change gets at the heart of what school is ultimately for: Helping kids make sense of the world around them, while preparing them for the future.

“This is the topic of the century, and not just because of the potential disasters ahead,” she said. “But because this is the future of the economy.”