Math and reading scores plummet on national test, erasing 20 years of progress

Chalkbeat | By Kalyn Belsha | September 1, 2022

In a grim sign of the pandemic’s impact, math and reading scores for 9-year-olds across the U.S. plummeted between 2020 and 2022.

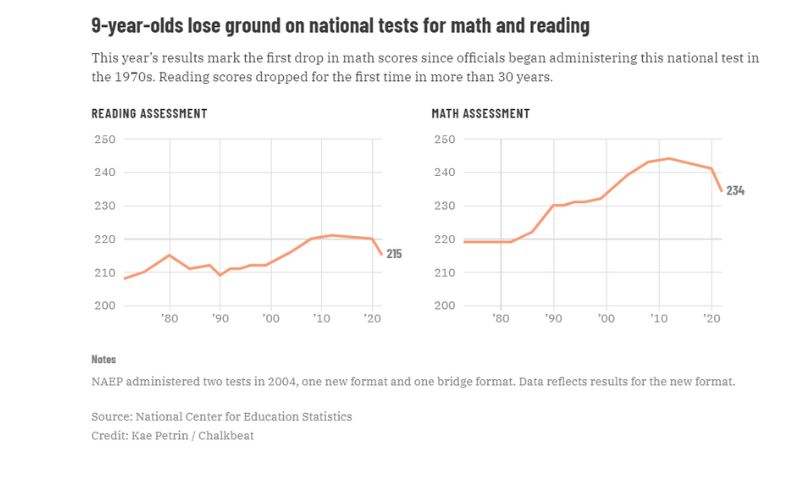

The declines erase decades of academic progress. In two years, reading scores on a key national test dropped more sharply than they have in over 30 years, and math scores fell for the first time since the test began in the early 1970s.

Put another way: It’s as if 9-year-olds were performing at the same level in math as 9-year-olds did back in 1999, and at the same reading level as in 2004.

Put another way: It’s as if 9-year-olds were performing at the same level in math as 9-year-olds did back in 1999, and at the same reading level as in 2004.

“I was taken aback by the scope and the magnitude of the decline,” said Peggy Carr, who heads the National Center for Education Statistics, which administers the test. “The big takeaway is that there really are no increases in achievement in either of the subjects for any student group in this assessment — there were only declines or stagnant scores for the nation’s 9-year-olds.”

The scores, released Thursday, are the first nationally representative look at how students across the U.S. performed in math and reading just before the pandemic compared with this year. They come from a long-running version of the National Assessment of Educational Progress, a test known as “the nation’s report card” that’s able to compare student achievement across decades.

The sample included nearly 15,000 9-year-olds from 410 schools, about two-thirds of whom were in fourth grade.

Carr said while her team usually shies away from ascribing a reason to score increases or decreases, it’s obvious in this case that the disruptions wrought by the pandemic were a major factor in the declines.

“It’s clear that COVID-19 shocked American education and stunned the academic growth of this age group,” Carr told reporters on a Wednesday call. “No other factor could have had such a dramatic influence on student achievement in a relatively short period of time.”

The scores could influence how state and district officials choose to spend their remaining COVID relief dollars — and fuel debates about whether public schools are adequately serving students in a time of great need. Many school districts already are devoting chunks of federal money to academic recovery, but there’s little evidence so far showing what difference those efforts have made for struggling students.

“Supporting the academic recovery of lower-performing students should be a top priority for educators and policymakers nationwide,” Martin West, a professor at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education and a member of the board that oversees the national test, said in a statement.

Federal education officials cautioned that these scores shouldn’t be used to penalize schools. Rather, Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona said in a statement, these results should spur states and schools to use their federal aid “even more effectively and expeditiously” on strategies like high-dosage tutoring, hiring more staff, and running after-school programs. High-poverty schools especially have an unprecedented amount of money at their disposal, but some have struggled to spend it.

The education department would be watching, Cardona said, to make sure schools are “directing the most resources towards students who fell furthest behind.”

Reading and math score declines were most severe among students who were performing at the lowest levels. That means kids who hadn’t yet mastered skills like addition and multiplication, or who were working on simple reading tasks, saw their scores fall the most.

The gap between higher- and lower-performing students was already growing before COVID hit, but federal officials say the pandemic appears to have exacerbated that divide.

“There is still a widening of the disparity between the top and the bottom performers, but in a different way,” Carr said. “Everyone is dropping. But the students at the bottom are dropping faster.”

Officials noted that when they asked students about the tools they had available to them during remote learning, higher-scoring students were more likely than their struggling peers to say a teacher was available to help them with their math or reading work every day or almost every day — a disparity that could have contributed to the growing divide.

There were some differences across subject areas. Declines in math were pervasive, but Black students saw a particularly sharp drop.

Reading scores dipped by similar amounts for white, Hispanic, and Black students. But reading scores held steady in city schools, rural schools, and for English learners. To Carr, those were the only bright spots in the data.

“The fact that reading achievement among students in cities held steady, when you consider the extreme crises that cities were dealing with during the pandemic, is especially significant,” she said.

Officials said while these scores are an important indicator of the pandemic’s effect on elementary schoolers, the data doesn’t offer any insight into how long it could take for students to rebound academically. That won’t be clear, Carr said, until there’s more district, state, and federal data to analyze.

Data gathered from other state and national tests this year show elementary-age students are starting to rebound in reading and math after students saw dips, or made less progress than usual, earlier in the pandemic. But by some measures, middle schoolers are recovering more slowly, or not at all — raising concerns about whether enough is being done to support older students, who have less time to catch up.

Schools have a tall order ahead this year: Academic recovery efforts have been hampered by a host of issues, including a rise in student absenteeism, staffing challenges, and growing student mental health needs. In some schools, educators are also contending with an uptick in behavioral challenges and classroom disruptions.

A trove of federal data slated for release in late October will shine more light on how older students are faring. That will include scores from fourth and eighth grade students across the U.S., in individual states, and in certain cities.

“I am a little worried,” Carr said. “It’s difficult to predict what the recovery will look like. We’ll just have to see.”