School Test Scores Start to Rise With Return of In-Person Classes

Still struggling are youngest students, who learned to read during Covid-19 pandemic, national study shows

The Wall Street Journal | By Sara Randazzo | March 23, 2022

The return to in-person classes this school year has helped students begin to learn again at a normal pace, a new national study shows, though many are still facing setbacks from months of pandemic-disrupted education.

The results show that children are making strides to overcome the challenges of the past two years, though the study echoes others in reporting that progress is weaker among students who haven’t yet learned to read and have only known a pandemic education.

“Were there signs of stabilization? Yeah, there really were,” said Gene Kerns, chief academic officer at Renaissance Learning Inc., which analyzed benchmarking test results from 4.4 million students from kindergarten to 12th grade in reading and 2.9 million students in math.

The overall downside is that performance hasn’t rebounded to pre-pandemic levels, he added. “There are not signs of a recovery if you define that as getting back to where we were performing before all this,” he said.

Districts across the U.S. use Renaissance’s Star test to assess student performance throughout the year. The study, out this week, compared results from fall and winter to see how the second full school year of the pandemic is affecting student learning. The results come from schools across all 50 states and the District of Columbia that used the computer-based tests in both school years.

Overall, students are performing worse so far in the 2021-22 school year compared with the prior year, in both reading and math. Fall-to-winter growth, however, improved this school year, and the gulf in scores from last year to this year shrank by winter.

Monroe County School District, which serves the Florida Keys and uses the Star tests, fully returned to in-person learning this school year after being partially remote during 2020-21. Virtual instruction in the Keys, spread across 100 miles, made it harder for many students to absorb their math lessons, said Amy Stanton, the district’s coordinator of mathematics.

Now, with students back in the classroom and getting regular feedback from teachers and classmates, Ms. Stanton said, “Once the understanding hits, it’s like a domino: ‘I get it, I get it, I get it.’” The district has tried to inject fun back into the classroom, using hands-on games beyond pure memorization of concepts to help math concepts stick.

Monroe County Superintendent Theresa Axford said that teachers were somewhat alarmed in the fall to see where kids were starting academically and emotionally, but that there has been steady progress since then. “Not every child is at the same level of proficiency, but every child can grow,” Ms. Axford said. “When you see that, you feel like you’re doing your job.”

Renaissance tracks progress through a metric called student-growth percentile, which is similar to the percentile measurements tracking a child’s weight and height, with 50 marking the typical person. From fall to winter, the median U.S. student-growth percentile in reading was 48 and in math it was 50, both 3 points higher than the growth recorded last school year. To get fully back to pre-pandemic levels, the metric needs to surpass 50 consistently, Renaissance said.

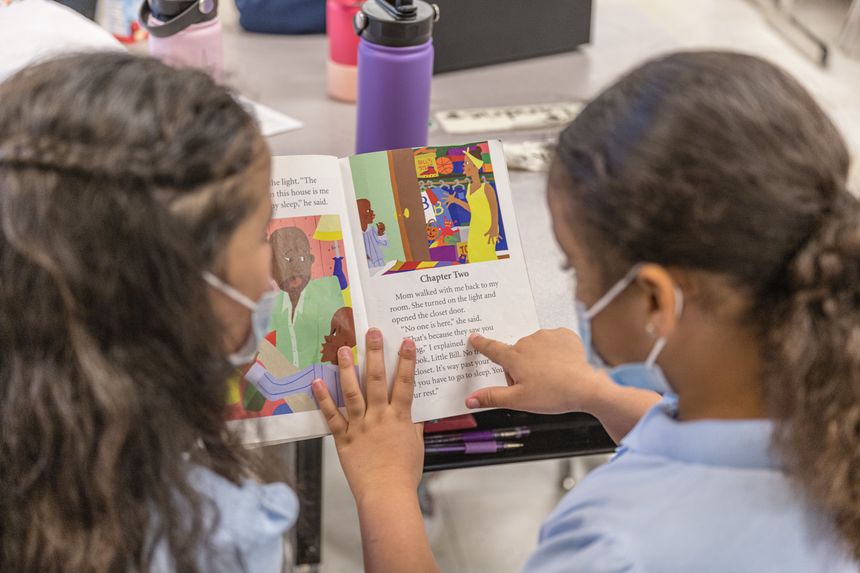

In the early days of the pandemic, math advancement took the biggest hit, which some attributed to parents being less comfortable helping with the subject during remote learning. Now, students who aren’t yet reading independently are struggling the most, with a median student-growth percentile of 35, indicating very low growth.

Making sure that the youngest students gain the reading skills they need by fourth grade, when reading begins to underpin most other subjects, is a concern shared by many educators nationwide.

Of students who attended programs at the Institute of Reading Development, a literacy organization, about 49% of those entering first grade this school year were reading below expectations, compared with 28% before the pandemic. It is a level that Josh Kizner, the institute’s vice president for partnerships, said hasn’t been seen in several generations.

Rena Gibbs, the coordinator of curriculum and instruction at the 3,500-student Cypress School District in Southern California, said: “They’re just not coming with those sounds and letters and scholarly habits we’re used to.” First-grade teachers have had to go back to the basics of making sure students know certain letter sounds, such as the “c” in cat, instead of jumping straight into introducing short words at the beginning of the year, Ms. Gibbs said.

“We feel a huge pressure,” Ms. Gibbs said. “We know if they don’t have those early literacy skills by the end of third grade, it does not bode well for their future.”

Mr. Kerns, from Renaissance, said that recovering from the disrupted learning will play out differently for each student, but that educators should look for growth above all else. “We can’t undo a pandemic,” he said.

Some administrators, including Dave Gibbons, director of curriculum at the 1,850-student Schuyler Community Schools in Nebraska, said pre-pandemic achievement levels can be reached again. He said coming out of the pandemic, he would like to teach fewer concepts at a deeper level, which he said could lead to “growth beyond where we’d been in the past.”