State, not school boards, will get final say on banned books

Orlando Sentinel | By Jeffrey S. Solochek | July 11, 2023

TAMPA — Hernando County elementary school students no longer have access to the book “Marvin Redpost: Is He a Girl?”

The school board banned it in June, with two of the five members voicing concerns that it could expose children to the topic of gender identity. But the tie-breaking vote from board chairperson Gus Guadagnino is what has parent Kim Mulrooney most upset.

Guadagnino told Suncoast News, a subsidiary of the Times Publishing Company, that he thought the book was “stupid” and he’d rather see children reading something more substantial. That’s not a legally valid reason for removing materials, said Mulrooney, who sat on the Pine Grove Elementary advisory panel that unanimously backed the book after a resident challenged it.

Mulrooney wants to appeal, but the district says the board vote is final. Soon, though, that should change.

This past spring, lawmakers added a provision to the law governing book objections that would allow parents to request a state magistrate review if they disagree with a school board’s action on a challenge. After hearing information from all sides, the magistrate would recommend a resolution to the State Board of Education, which would make a final decision.

School districts would be responsible for the cost of the review.

“I am going to find out how I can do this,” Mulrooney told the Tampa Bay Times. “There’s no reason this book should be pulled.”

The 1993 title from author Louis Sachar “offers a sidesplitting take on the differences between girls and boys,” according to a review on Amazon. Mulrooney said its main character is not transgender and does not wish to be a girl, although he worries he could turn into a girl if he kisses his elbow — something a classmate told him could happen.

She said the story offers positive messages about boys and girls getting along and does not address gender in any sexual manner.

Pulling the book because it’s “stupid” also does not align with Hernando board policy, Mulrooney argued.

District policy says the board may review and remove challenged material “if it contains content that is pornographic or prohibited under (statute), is not suited to student needs and their ability to comprehend the material presented, or is inappropriate for the grade level and age group for which the material is used.”

The Florida Department of Education currently is collecting public input on a proposed rule to carry out the magistrate process. It has not released draft language for the public to see.

During debate on the bill — which also directs schools to remove any books within five days of receiving a complaint about sexual content — lawmakers advanced the idea of the magistrate as a way for communities to have another way to get their voice heard.

They noted that the avenue would be open to anyone, whether they are fighting to get a book returned to the shelves or get it taken away.

Stephana Ferrell, co-founder of Florida Freedom to Read Project, raised concerns that the model could have unintended consequences.

Because the cost of a magistrate review would be borne by districts, she said, some districts might seek to avoid the expense by taking books out of libraries and classrooms — or not buying potentially controversial ones — before any objections can be made. The law says that parents may seek a magistrate when challenging a board’s action on an objection to specific material.

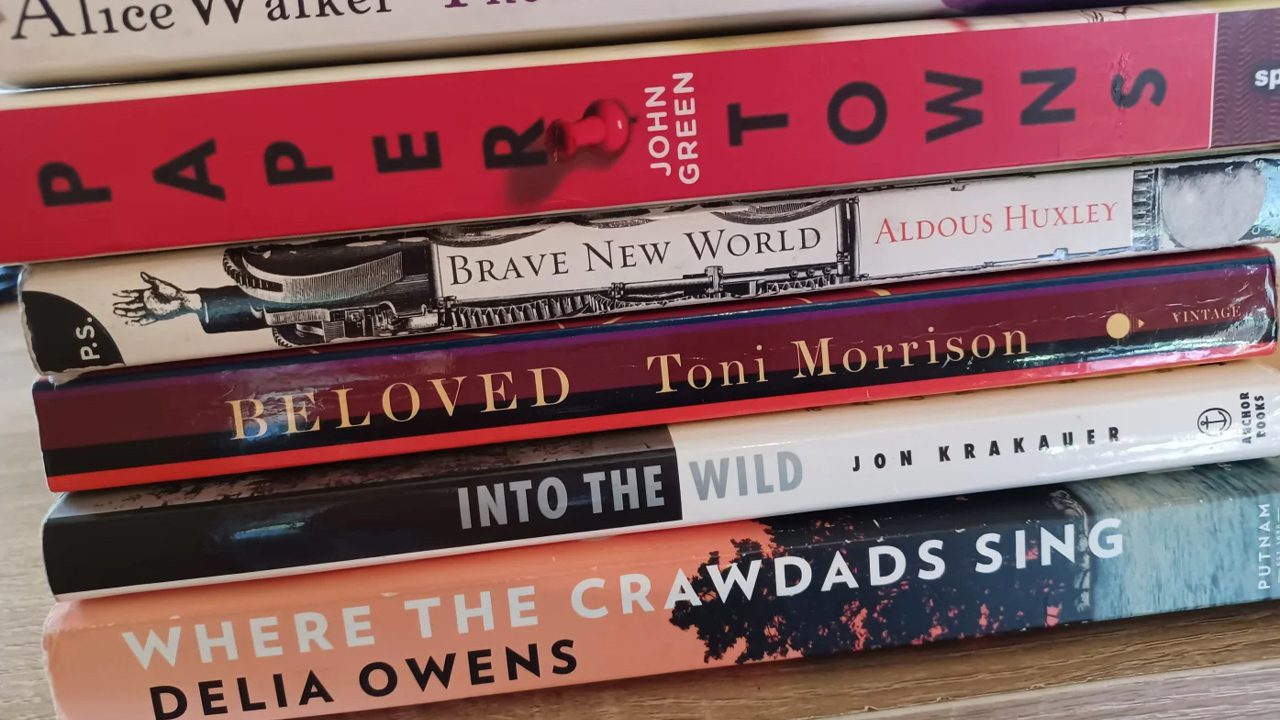

Some districts already have precluded public involvement in high-profile book disputes by skirting the official challenge process. In Pinellas County, for instance, all decisions about Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” were conducted privately by staff after the parent with concerns about the book never made a formal challenge.

Ferrell suggested the balance of power would remain in the hands of those seeking to remove books, not keep them.

State Rep. Anna Eskamani, D-Orlando, further questioned whether the magistrate process could be objective, “given who’s in charge of the department.” The State Board of Education has seven appointees by Gov. Ron DeSantis, and education commissioner Manny Diaz recently told a Moms for Liberty convention that public education is too “woke.”

Karen Jordan, a spokesperson for the Hernando County district, said the administration and board have no plan to revisit “Marvin Redpost: Is He a Girl?” or to open the door for reconsideration.

She said similar questions had been raised when the board banned other books, such as “The Sun and Her Flowers” by Rupi Kaur on May 30.

Once the state completes its rules for the magistrate, Jordan said, the district will follow that process and abide by any decisions made.

“Clearly we want to be respectful of what the State Board of Education says,” she said.