Statue of trailblazing educator and civil rights activist Bethune unveiled in U.S. Capitol

Florida Times-Union | By Eileen Zaffiro-Kean | July 14, 2022

WASHINGTON, D.C. — On a July day in 1875, Mary McLeod Bethune came into the world in a small log cabin on a South Carolina rice and cotton farm. Slavery and the Civil War had just ended 10 years earlier. Her parents were former slaves, and she was their 15th child.

Nothing about her beginnings formed a launching pad for achievement and greatness, yet Bethune soared. And now her tenacious, unrelenting quest to help others has taken her somewhere probably unimaginable to her and her parents when she was growing up in a tiny rural town 140 years ago.

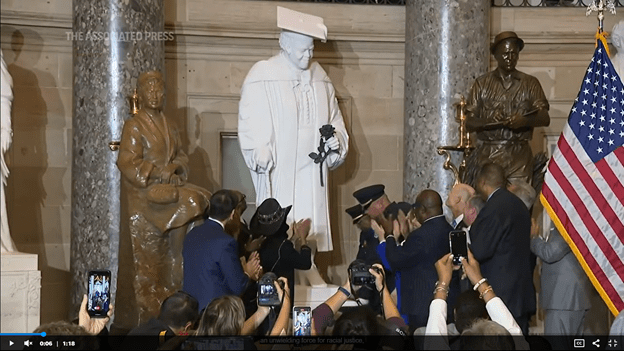

On Wednesday morning, an 11-foot-tall marble statue depicting Bethune was unveiled inside the U.S. Capitol building’s National Statuary Hall, which is built in the shape of an ancient amphitheater and has colossal columns formed out of variegated Breccia marble quarried along the Potomac River.

In the huge 229-year-old building where U.S. presidents, senators and House representative have walked, debated and legislated since the late 1700s, the gleaming white work of art will stand for generations to honor the trailblazing civil rights pioneer, stateswoman and educator.

Sitting just a few feet away from the towering creation Wednesday were several of Bethune’s descendants, including her great grandniece, Jereleen Hollimon-Miller, who is the mayor of Bethune’s hometown of Mayesville, S.C.

Also in Statuary Hall to honor the 20th century champion for Black Americans were some of the most powerful elected leaders in the country: U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, House Majority Whip James Clyburn, U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL), U.S. Rep. Val Demings (D-FL), U.S. Rep. Michael Waltz (R-FL), U.S. Rep. Kathy Castor (D-FL) and U.S. Rep. Frederica Wilson (D-FL).

Pelosi, who noted that she’s had a bust of Bethune in her office for decades, said Bethune “devoted her life to opening doors of opportunity for more Americans.”

She said the statue will now “ensure that young people, all young people, but especially young black women, girls … and young boys as well” will come to the Capitol and see a reflection of our “nation’s beautiful diversity, beautiful success and greater possibilities for them in their future.”

“How poetic and how wonderful it is that she was able to do so much,” Pelosi said. “It is a glorious day in the capital of the United States.”

Bethune ‘made what seemed impossible, possible’

“I can’t think of someone more deserving than Mary McLeod Bethune,” Waltz said in an interview before Wednesday’s unveiling ceremony. “She’s a legend.”

Waltz said he was “thrilled to be a small part of” the event to celebrate the placement of the new Bethune sculpture, which now stands beside the statue of Rosa Parks, an activist in the civil rights movement best known for her pivotal role in the Montgomery bus boycott.

U.S. Senate Chaplain Barry C. Black, who delivered the invocation at Wednesday morning’s ceremony, said Bethune “was a drum major for truth, justice and righteousness.”

Demings said Bethune “made what seemed impossible, possible” and she “was determined to make an opportunity for every child.”

“Through faith she dared to be brilliant and let her light shine, so anyone who looked could see and dare to have their own dreams,” Demings said.

Castor said Bethune was being honored “at a time of competing ideologies to heal and unite.”

Also at the unveiling was U.S. Sen. Rick Scott, (R-FL), who during his years as Florida’s governor signed a bill to commission the statue of Bethune to represent Florida in the U.S. Capitol. Scott was Florida’s governor from 2011-2019. It was in 2016 that the Florida legislature passed statue replacement legislation, and in 2018 Bethune was chosen for one of the two spots to represent Florida in Statuary Hall.

Dozens of Daytona Beach-area residents were also in the nation’s capital Wednesday to celebrate the new statue and honor the civil and human rights leader who became a force in Washington, D.C., was an advisor to five U.S. presidents and fought for women’s right to vote. Bethune also started a small school for girls in Daytona Beach that evolved into Bethune-Cookman University, and she took on Daytona Beach leaders in the early 1900s to secure the most basic rights for that city’s Black residents.

Those who made the trip to the capital this week include Bethune-Cookman Interim President Lawrence M. Drake II, Bethune-Cookman board trustees and alumni from across the country, and the Florida leaders who over the last six years secured the government approvals and raised nearly $1 million to make the statue possible.

“Our hearts are rejoicing today,” Drake said. “She left a lasting mark on the country and world.”

Also in Statuary Hall Wednesday were Nancy Lohman, president of the Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune Statuary Fund Board, and several additional members of that racially and politically diverse board that was so key in making the statue project possible.

“(Bethune’s) worldview provided her with a unique vision where humanity is able to breathe freely, harness their strengths and lead full lives,” Lohman said as she spoke to the more than 100 people gathered in Statuary Hall. “She continues to inspire people of all backgrounds to build a better world, and she guides us with her timeless instruction in her last will and testament – a thirst for education, a desire to live harmoniously with one another and responsibility for our young people.”

‘The culmination of a magnificent journey’

Also in attendance were Johnny McCray, president of the Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune National Alumni Association, and the Bethune-Cookman University Concert Chorale, whose members stood on the balcony overlooking the round Statuary Hall room. With their angelic tones floating through the hall, they sang “If I can help somebody along the way, then my living shall not be in vain.”

Daytona Beach Mayor Derrick Henry also made the cut for visitors allowed inside for the unveiling ceremony inside the Capitol.

“It is the culmination of a magnificent journey from the cotton fields to Statuary Hall,” Henry said after the ceremony. “As a member of the (statue project) board and mayor of Daytona Beach, this is my proudest moment for our city.”

Those who weren’t chosen for one of the coveted slots to watch the unveiling in person were able to watch the event live on WESH-Channel 2, on WESH’s website, via a link for a livestream feed, and at watch parties in Washington, D.C., and on the Bethune-Cookman campus.

Also at the hour-long ceremony was Nilda Comas, the master sculptor who thoroughly studied Bethune’s life and painstakingly created the statue of her inside an historic artists’ studio in a 1,000-year-old hamlet on the northern coast of Tuscany. Comas’ boyfriend, daughter, two brothers and sister-in-law were all there to celebrate the achievement of the artist who lives in both Florida and Italy.

Comas, the first Hispanic sculptor selected to create a statue for the National Statuary Hall state collection, also crafted a bronze statue of Bethune that will be unveiled on Daytona Beach’s Riverfront Esplanade the morning of Aug. 18. Comas earned a Master of Fine Arts degree from the New York Academy, and she studied at the Accademia di Belli Arte in Carrara, Italy.

“Florida has chosen the perfect sculptor to reside in history with Dr. Bethune, and Dr. Bethune’s statue represents the best of who we are as Floridians and as Americans,” Lohman said.

Lohman also noted in her remarks that during a 1948 National Council of Negro Women event Bethune said, “In the final years of my life, I dare to work for the dream of a memorial for all women because the time has come for it, and it is a cause worth every sacrifice.”

“That time has now come,” Lohman said. “It is today. And it is in this pristine marble masterpiece in her likeness.”

A new milestone in National Statuary Hall

The Bethune statue is the first representing a Black person, male or female, in the state collection inside Statuary Hall. There are four other Black people represented in other parts of the Capitol: Martin Luther King Jr., Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth and Rosa Parks.

Statuary Hall will be the permanent home of the artfully chiseled creation, which was carved out of a 13-foot-long block of white marble that could be the last ever culled from the Tuscan quarry Michelangelo used for his masterpiece statue of David more than 500 years ago.

Every part of the statue tells a story about Bethune. The walking stick she holds in her right hand is modeled after a gift Bethune received from President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The black rose in her left hand is a reminder of how she referred to her students as black roses. The stacked books at her feet are each sculpted with a tenet of her Last Will and Testament, which was full of her core values.

Statuary Hall is a chamber just off the Capitol’s rotunda. The hall was the original meeting place of the U.S. House of Representatives, and since 1864 it’s been devoted to sculptures of prominent Americans.

Each state is represented in the Capitol by two statues. For many decades, Florida had been represented by works depicting John Gorrie and Edmund Kirby Smith.

Gorrie is the father of ice-making and air-conditioning technology. There’s a museum dedicated to him in Apalachicola, and an impressive monument to him was erected in 1899 by the Southern Ice Exchange.

Smith was born in St. Augustine in 1824 to a Connecticut family. He left Florida for military prep school when he was about 12 years old and never looked back.

He became a Confederate general, and he commanded forces in the area around Mississippi and Arkansas, a theater cut off from the rest of the Confederacy after the Union captured Vicksburg in 1863.

The Gorrie statue will remain in the Capitol building, but Bethune’s sculpture will replace the nearly 100-year-old bronze sculpture of Smith. The Smith statue was removed last year and placed in temporary storage at the Museum of Florida History in Tallahassee.

Wednesday was a day to celebrate for the dozens and dozens of people who traveled to Washington, D.C., to mark the historic day. While many of them weren’t able to attend the limited-seated unveiling, there were plenty of other events to mark the occasion.

For some, the celebrating started Sunday, the day Bethune was born in 1875. On Sunday morning, there was a worship service and birthday party for Bethune at Asbury United Methodist Church in Washington, D.C. Late Sunday afternoon, there was a three-hour Bethune birthday party at Lincoln Park in the city’s metro area complete with jazz, birthday cake and punch.

On Tuesday morning, there was a bus tour showing the places Bethune frequented on her many trips to Washington, D.C. And Tuesday night there was a black tie reception for major statue project donors at the Florida House, which is located a block east of the Capitol.

More than 500 donors contributed to the project since 2018. Five individuals and corporations gave $50,000 or more, and another 45 gave at least $5,000.

Brown & Brown, Inc., insurance company was one of the $50,000 and greater donors, and company CEO J. Powell Brown was among those at Wednesday morning’s statue unveiling.

The black tie reception at the Florida House, a Victorian-style row house built in 1891 that has been Florida’s state embassy since 1973, included remarks from Castor and Waltz, an opera performance and interpretive drama presentations.

The Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune National Alumni Association planned to hold a reception Wednesday evening on the campus of the Howard University School of Law. A tour of the Washington, D.C., townhome Bethune owned and lived in from 1943 to 1955 was also planned.

Mary McLeod Bethune’s backstory

Bethune was toiling in the cotton fields by the time she was 5 years old, but she was able to go to the one-room school a few miles away. She became the first person in her family to learn to read and write.

It was a small opportunity, but she parlayed her rural South education into a prolific career and life. She also graduated from the Scotia Seminary, a boarding school in North Carolina, and attended Dwight Moody’s Institute for Home and Foreign Missions in Chicago.

When she started a school for girls in Daytona Beach in 1904, she rented a small house for $11 per month. She made benches and desks from discarded crates, pencils from burned wood and ink from elderberry juice.

The Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls site bordered Daytona Beach’s trash dump, so Bethune raised money selling sweet potato pies, ice cream and fried fish to crews at the dump.

That school eventually grew into Bethune-Cookman University, which has helped generations of Black students pursue an education beyond high school.

Bethune’s endeavors increasingly took her to Washington, D.C., and a fateful meeting there led to her friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt and new possibilities for the causes she championed.

More opportunities opened up for Bethune as she became an advisor to U.S. presidents including Franklin D. Roosevelt. She was appointed to numerous commissions including Calvin Coolidge’s Child Welfare Conference, Herbert Hoover’s National Commission on Child Welfare, and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Black Cabinet.”

She became the only Black woman to help the U.S. delegation that created the United Nations charter. She also created the National Council of Negro Women, directed the Office of Minority Affairs in the National Youth Administration, and became a general in the Women’s Army for the National Defense. Roosevelt’s appointment of her as director of the National Youth Administration made her the first Black woman to lead a federal agency.

Her disadvantaged start in life only seemed to make her more determined and toughen her for the challenges she ran up against throughout her 79 years. When the Ku Klux Klan came to her school in Daytona Beach riding horses and carrying torches, Bethune stood alone and stared down the men in white robes. She told them she would just build another school if they set fire to her campus.

“Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune is probably one of the most important civil rights leaders,” Patrick Coggins, a multicultural education professor at Florida’s Stetson University, said in an interview last year.

She connected herself to the national movement of women pushing for the right to vote, Coggins said. U.S. presidents dating back to Coolidge in 1923 appointed her to commissions and leadership positions.

“This was not a woman to be taken lightly,” Coggins said. “She was brilliant, organized and able to raise money. She was good at building contacts and coalitions with whites. She found whites who believed in her and her strategy.”

Coggins said she galvanized the religious community to see Jim Crow laws weren’t going to be a good idea in the long run. She managed to avoid being lynched or attacked in other ways probably because the KKK and other racists “misread her depths and potential,” he said.

“I think we’re looking at a saint and a special person,” he said.

Bethune was constantly juggling projects many people might not have been aware of.

She worked with Eleanor Roosevelt to integrate the military during World War II and help the Tuskegee Airmen become the first Black military aviators in the United States’ armed forces.

She and Eleanor Roosevelt also worked together on international human rights endeavors.

“She really laid the blueprint for nonviolence and how you advocate for civil rights, human rights and women’s rights,” Coggins said.