Teacher Shortages by State and How Officials Are Trying to Fix the Problem

Florida has the highest number of teacher vacancies while Utah has the lowest. Learn where your state falls and how officials are working to combat the teacher shortage.

Campus Safety | By Amy Rock | April 18, 2023

A survey released earlier this year by the National Education Association (NEA) found 55% of educators want to leave teaching earlier than they originally planned. The main reason? Burnout from massive labor shortages.

About 1 in 6 teachers expressed they would likely leave their job pre-pandemic. This increased to 1 in 4 by the 2020-21 school year. While teacher shortages clearly predate the pandemic, particularly for substitute teachers and in hard-to-staff subjects such as math, science, special education, and bilingual education, these shortages have grown in the past two years and expanded to encompass other positions such as bus drivers, school nurses, and food service workers, CS previously reported.

The pandemic kicked off the largest drop in education employment ever. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of people employed in public schools — not just teachers — dropped from almost 8.1 million in March 2020 to 7.3 million in May. Employment has grown back to 7.7 million since then, but schools are still short nearly 360,000 positions, according to The Hechinger Report.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are currently 567,000 fewer educators in America’s public schools today than there were before the pandemic. Nationally, the ratio of hires to job openings in the education sector has reached new lows as the 2021-22 school year started. It currently stands at 0.57 hires for every open position, according to BLS’ Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS).

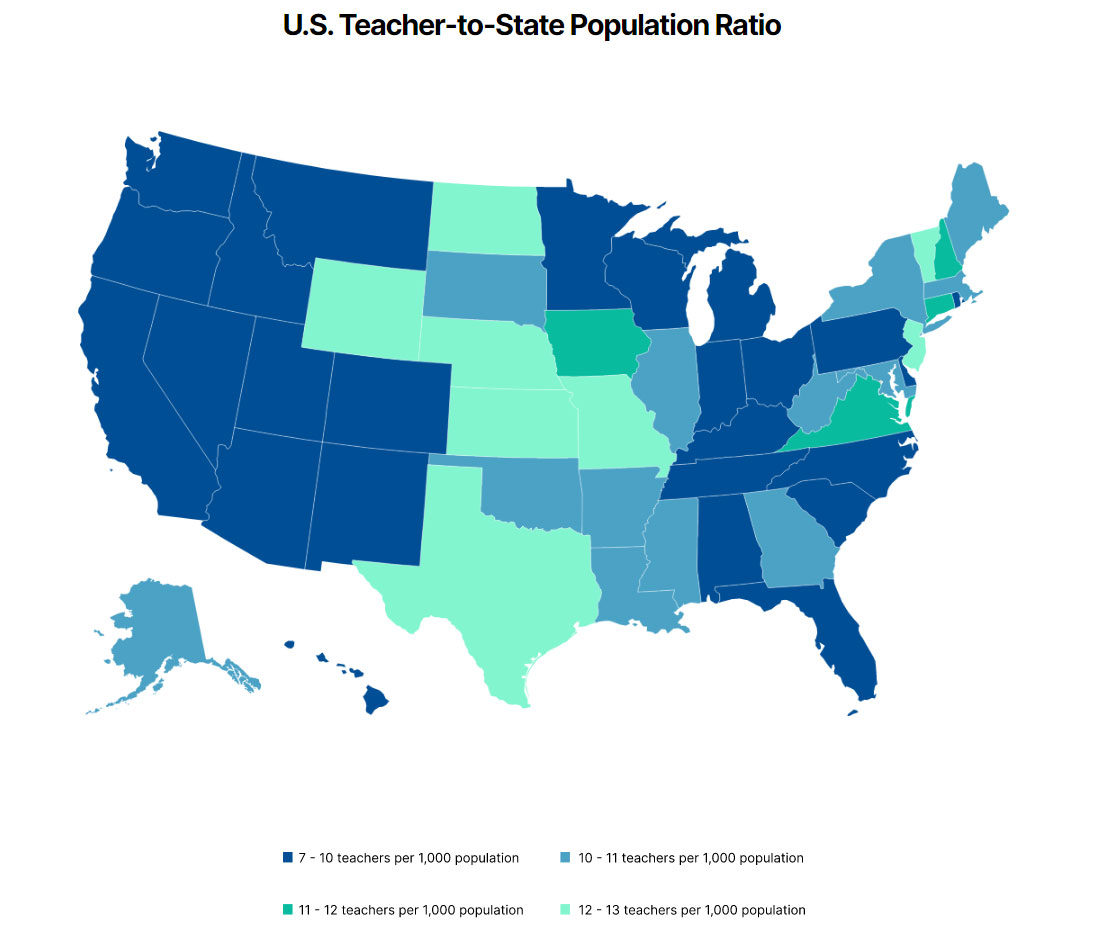

Number of Employed Teachers by State

To see where each state stands in regard to teacher staffing, Scholaroo, a scholarship search platform, compared the number of currently employed teachers in each state to the state population.

Please note these findings don’t take into account what percentage of each state’s population is school-aged or what the enrollment numbers are. For instance, only 18.8% of Vermont’s population is under the age of 18 while 29% of Utah’s population is under 18, according to PRB. Florida, which ranks the lowest in teacher-to-state population ratio, has the second-highest percentage of homeschooled children at 22.5%, says a study conducted by Q for Quinn.

The researchers created four categories. Here’s the breakdown and also the number of states that fall under each category:

- 7-10 teachers per 1,000 population: 25 states

- 10-11 teachers per 1,000 population: 13 states

- 11-12 teachers per 1,000 population: 4 states

- 12-13 teachers per 1,000 population: 8 states

Source: Scholaroo

Below are both the 10 best and the 10 worst states when it comes to teacher-to-state population ratio. The full list and a more detailed breakdown, including an interactive map, can be found here.

10 States with Highest Teacher-to-State Population Ratio

- North Dakota

- Nebraska

- Vermont

- New Jersey

- Wyoming

- Texas

- Missouri

- Kansas

- New Hampshire

- Iowa

Scholaroo also recently conducted another study on student safety, taking into consideration school security measures, bullying prevention programs, and other initiatives designed to ensure students feel safe at school. New Jersey, Vermont, and New Hampshire — all in the above list — ranked in the top 10.

10 States with Lowest Teacher-to-State Population Ratio

- Florida

- Oregon

- California

- Nevada

- Hawaii

- Michigan

- Washington

- Arizona

- Kentucky

- Tennessee

Nevada, California, and Arizona ranked in the bottom 10 states in Scholaroo’s student safety survey.

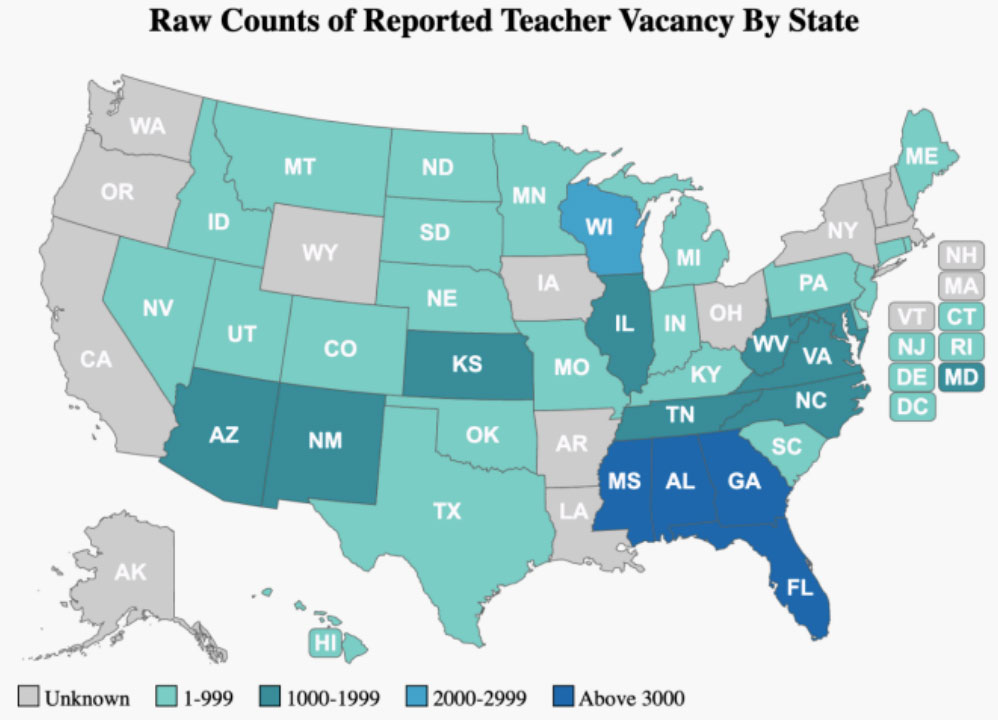

Teacher Shortages by State

Perhaps a more accurate way to assess the current teacher shortage is by looking at teacher job vacancies by state. An Aug. 2022 study released by the Annenberg Institute at Brown University found there are at least 36,000 vacant full-time teaching positions in the United States with the number potentially as high as 52,800 (some states have not provided figures). The breakdown by state can be seen in the graphic below.

Source: Nguyen, Tuan D., Chanh B. Lam, and Paul Bruno. (2022). Is there a national teacher shortage? A systematic examination of reports of teacher shortages in the United States. (EdWorkingPaper: 22-631).

The highest number of open teaching positions are concentrated in the south and lower Atlantic where around 22,000 positions are vacant — almost three times higher than in the Midwest. Georgia had the highest number of vacancies (3,112) for the 2019-2020 school year. More recently, during the 2021-2022 school year, Florida had the most vacancies with 3,911 positions unfulfilled. That same school year, Mississippi and Alabama had over 3,000 vacancies. Sixteen states reported under 1,000 vacancies during the 2021-2022 school year. The states with the fewest vacant teacher positions were Utah (37), Missouri (38), and Nebraska (42).

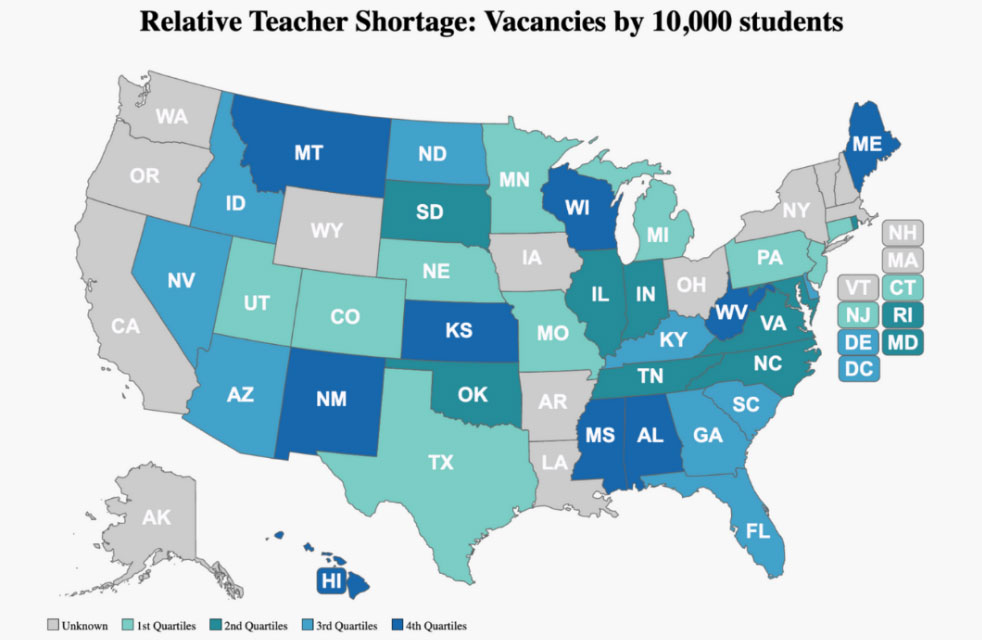

The researchers also broke down vacancies by 10,000 students, noting, “When student population is taken into consideration, the distribution changes substantially, and there is less of a geographical concentration of vacancy.” For instance, in the graphic below, there is no longer a cluster of high vacancy states in the southeast. However, Mississippi and Alabama are still among the states with the highest number of teachers needed for every 10,000 students.

Source: Nguyen, Tuan D., Chanh B. Lam, and Paul Bruno. (2022). Is there a national teacher shortage? A systematic examination of reports of teacher shortages in the United States. (EdWorkingPaper: 22-631).

Increased Mental Health Issues, School Violence Continue to Impact the Teacher Shortage

In addition to teachers, there are also significant shortages of mental health professionals in schools. The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) recommends at least one counselor for every 250 students. The national average is currently around 444 students per counselor. Compounding this shortage, child mental health concerns and school violence have skyrocketed since the pandemic.

A survey of 15,000 educators found a growing trend of students verbally and physically harassing teachers, as well as parents engaging in online harassment and unprovoked retaliatory behaviors against teachers. One-third of surveyed teachers reported experiencing at least one incident of verbal or threatening violence from students during the pandemic, and over 40% of school administrators reported verbal or threatening violence from parents. All respondents reported significant verbal or threatening victimization from students, parents, colleagues, or administrators.

As for physical violence, school staff (i.e., paraprofessionals, school counselors, instructional aides, and school resource officers) reported the highest rates with 22% reporting at least one incident of physical violence by a student during the pandemic.

While many factors come into play regarding an increase in school violence, most who work in the education industry will agree that the ongoing staffing shortage is unequivocally one of those factors. It is a complete Catch-22 situation. With violence in schools on the rise, more teachers are leaving the profession and many who were once interested in becoming teachers have now changed their career paths due to safety concerns. Each issue fuels the other, and various entities are trying to come up with ways to combat the shortage.

How Is the U.S. Trying to Fix the Teacher Shortage?

Entities big and small — from the federal government to individual schools — are trying out different ways to combat the teacher shortage. In Aug. 2022, the Biden Administration unveiled a three-point plan to address teacher shortages:

- Partner with recruitment firms to find new potential applicants

- Subsidize prospective teachers’ training

- Pay teachers higher salaries

To fulfill the first part, ZipRecruiter has launched a new online job portal for K-12 jobs. Additionally, Indeed facilitated virtual hiring fairs for educators and Handshake hosted a free virtual event in October to help current undergraduate students learn about careers in education.

To subsidize training, the White House recommended policymakers use federal funding to establish more teacher-apprenticeship programs. U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona and now former Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh said registered apprenticeship programs in Iowa and Tennessee could be replicated across the country. Last year, Iowa launched a grant program that helps high school students earn a paraprofessional certificate and an associate degree. It also helps current paraprofessionals earn their bachelor’s degree so they can teach — all while gaining first-hand experience in the classroom. The funding covers candidates’ tuition and fees as well as an hourly pay rate of $12 for high school aids and 50% of the wages that districts already pay paraprofessionals.

Walsh said the Labor Department would prioritize the education sector in future apprenticeship funding, including its next round of more than $100 million in grants.

“There’s no reason we can’t have successful apprenticeships in the United States of America; they do it in Europe all day long,” he said.

To pay teachers more, Cardona and Walsh also urged states and districts to use federal pandemic recovery funds. New data shows that on average, teachers make 33% less than other college-educated workers.

“If we’re serious in addressing the teacher-shortage issue, we must first address the teacher-respect issue,” said Cardona. “And that means first and foremost paying our teachers a livable and competitive wage.”

A recent analysis from FutureEd found nearly a third of the country’s 100 largest school districts have increased teachers’ paychecks through bonuses, raises, and college loan forgiveness by using federal pandemic relief funds. Other recent research found that raising compensation does help retain teachers. A study of Florida shortage initiatives found a state loan forgiveness program and a bonus program aimed at teachers in shortage subjects reduced teacher turnover, and annual bonuses of $2,500 were enough to lower attrition among special education teachers.

Districts Shortening School Weeks, States Easing Teacher Requirements

In Texas, the Jasper Independent School District changed to a four-day school week in 2022 to incentivize more teachers to apply for jobs. Since then, nearly 60 school districts across the state have also made the switch. Districts in Colorado, New Mexico, Idaho, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Texas have also moved to a shorter school week. The move to four-day weeks is most popular in rural areas, where districts can save on utilities and cut the miles put on their school buses. About 90% of districts that have adopted the four-day week are in rural areas. The total number of districts adopting the four-day schedule has increased more than 30%, from 650 in 2020 to 850 now, reports EdSource.org.

Some states and districts are responding to shortages by reducing the qualifications to enter the classroom. In 2021, California started allowing teacher candidates to skip basic skills and subject matter tests if they have taken approved college courses, reports EdSource. New Mexico’s Public Education Department decided to eliminate subject skills tests as a requirement for people earning teaching certifications by 2024, according to The Santa Fe New Mexican. Instead, prospective teachers will be allowed to submit portfolios demonstrating their teaching competency.

Oklahoma eliminated its General Education Test as a certification requirement, and Missouri now only looks at a prospective teacher’s grades earned in select courses required to become a teacher. Alabama lowered the cutoff scores for its teacher certification exams. In the state’s Black Belt, there were no certified math teachers during the 2021-2022 school year in Bullock County’s public middle school.

Arizona now allows people without a college degree to begin teaching so long as they are currently enrolled in college. At the beginning of the current school year, schools in Mesa piloted a team teaching model to combat declining enrollment and teacher shortages. At Westwood High School, four teachers instruct 135 students in one giant classroom.

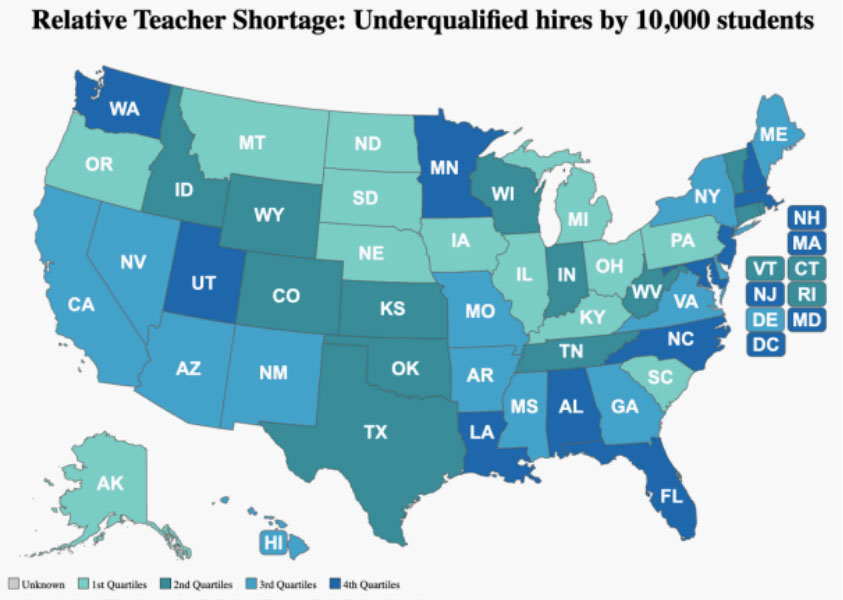

The aforementioned Brown University study also looked at the number of unqualified hires by state, as depicted in the graphic below. The researchers estimate there are 163,000 positions being held by underqualified teachers.

Source: Nguyen, Tuan D., Chanh B. Lam, and Paul Bruno. (2022). Is there a national teacher shortage? A systematic examination of reports of teacher shortages in the United States. (EdWorkingPaper: 22-631).

The highest quartile includes six states in the South, three each for the Northeast and West, and one in the Midwest. Illinois has the lowest number of underqualified teachers at 1.17 positions per 10,000 students while New Hampshire has the highest at 348.79. Notably, New Hampshire has not reported teacher shortage areas to the U.S. Department of Education since the 2019-2020 school year, according to the report.

Colleges and Universities Working to Improve Shortage

Colleges are trying to do their part as well. A March report from the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education showed that the number of people completing a teacher-education program declined by almost a third between the 2008-2009 and 2018-2019 academic years. In response, Washington, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Nevada, and New Mexico now offer teacher programs at community colleges.

In Massachusetts, the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education is offering incentives to colleges and universities by only approving new teacher training programs if they involve fields where there are shortages. The Colorado Department of Higher Education is targeting rural shortages by offering $10,000 stipends to teacher candidates who work in rural communities for a year with half the cost covered by the state and the other half by the candidates’ colleges. According to the nonprofit National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ), in 2020, Hawaii started paying special education teachers $10,000 more than their peers. In just one year, the initiative drew in 300 new special educators, cutting the shortage by half.

The University of South Carolina is partnering with the Charleston Country School District to use federal COVID-relief aid to train teaching assistants and other school staff to teach math and other subjects with significant job vacancies.

Overall, the root causes of the nationwide teacher shortage include low pay, increased scrutiny, and poor working conditions. While some of the strategies outlined above are new and their full impacts have yet to be seen, the only way to know if something works is by trying it out. And it seems like schools are willing to try almost anything at this point.

Curious about how your state is trying to recruit and retain teachers? News Nation Now conducted an impressive state-by-state deep dive. Check it out here.