Teachers rethink grading as many students struggle during the pandemic

They want to show “grace,” but also not mislead parents or children about academic progress.

Tampa Bay Times | by Jeffrey S. Solochek | December 17, 2020

Nick Amheiser doesn’t consider himself a pushover.

A history teacher at Meadowlawn Middle School in St. Petersburg, he doesn’t give his studentsextra credit and doesn’t pad grades.

“I’m not nice,” Amheiser said. “They get what they get.”

At the same time, he said, failing his class isn’t easy. He offers students opportunities to show what they know.

Yet as Amheiser reviewed his first semester grade book, he couldn’t miss the signs. Nearly 90 percent of students attending remotely were failing, while in-person students didn’t have nearly as many F’s.

“It’s mostly because they’re not doing anything,” he said of his online learners.

That pattern has become common as the pandemic continues to disrupt one of the most basic functions in any classroom — grading. How do teachers assess students they’ve seen only on a screen? What grade do you give when they don’t complete assignments, yet you know they’ve had difficulties with computer access?

In the spring, when all students were forced into online learning, one answer was the “grace before grades” approach. It offered leniencyduring a historically difficult time, an acknowledgment that the distractions of distance learning are real.

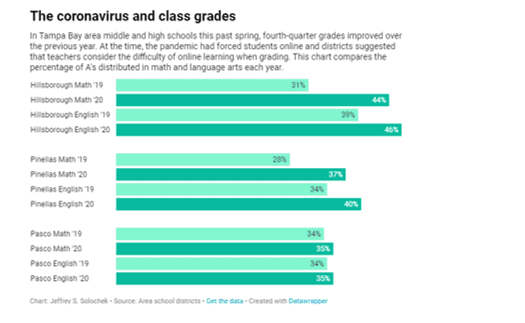

The result, according to school district records, was a marked increase in A’s when comparing the fourth quarter of the 2019-20 school year — at the start of the pandemic — with the same quarter a year earlier.

In Hillsborough County, 46 percent of high school students received A’s for the spring quarter in their English/language arts classes, compared to 38 percent the previous year. The increase was twice as much in math classes.

InPinellas County, six traditional high schools reported double-digit increases in A’s — from a 10 percentage-point rise at Seminole High to a 16-point surge at Osceola Fundamental High.

Students’ F grades also increased in the spring in the two districts, though mostly incrementally and primarily for those teens who gave their teachers nothing to grade.

Schools aim to balance grace, grades on report cards

As the pandemic wore on, concerns spiked that report cards were not reflecting the “COVID slide” that so many educators and others anticipated.

State officials told districts to monitor children’s progress throughout the fall. Theyexpected data would help determine whether in-person and live-remotemodels were working. As the grades came in, the struggles — particularly among virtual students — became clear.

“What we did see in middle and high schools was students who were at home were two times as likely to have a D or F,” said Kevin Hendrick, Pinellas associate superintendent for teaching and learning.

One thing stood out to Hendrick, though. In terms of understanding materials, the remote students across the district were not necessarily doing worse.

Like Amheiser, he found the difference came in attendance and work completion, both in the spring and in the fall.

To prepare for the spring 2021 semester, Florida Department of Education leaders instructed school districts to tell families in writing where students stood academically, and to encourage those who have fallen behind to return to face-to-face classes.

As the fall semester draws to a close, the situation with grades has become more tense, as schools seek to balance the goal of grace with the demand for progress.

That tension has prompted a conversation about what grades mean and how they should be calculated — during the pandemic and beyond. A key question is whether students should receive grades based on their knowledge at the end of a term or on materials completed while still learning the subject.

Douglas Reeves, founder of Boston-based Creative Leadership, saidFlorida led the nation three decades ago in transitioning to a standards-based education system. The move meant students should be evaluated against expected outcomes and not against an average of their performance over the year.

“That bears directly on today,” said Reeves, a leading proponent of changing grading models.

He said students might be earning F’s based on assignments submitted — or in many cases not submitted — but it’s “very clear” they should be assessed based on where they are at the end of the course.

“There are students who are way, way behind,” Reeves said.“They lost not just three months but as much as a year.”

Giving them an F solves nothing, he said, pointing to studies indicating that students with sagging gradesare more likely to abandon hope of success in high school. They also find themselves at risk of losing access to college scholarships, he said.

“Give them an IP (in-progress grade). Say, ‘If you come back, we can catch up. Then I’ll give you the grade which you deserve,’” Reeves said. “If we don’t do that, I’m afraid what we’re going to have is a dropout time bomb.”

‘Are you mastering the standards?’

Such concerns are real for localeducators. They want to find ways to get students more engaged, an issue that resonates in normal times, too.

In order to know who needs more attention, though, they say they musttrack progress, in addition to attendance and other related matters. That can mean assigning grades.

But teachers have some leeway, said Terry Connor, chief academic officer for Hillsborough County schools.

Districts don’t tell educators how to grade, he said, beyond insisting that the marks indicate a student’s level of proficiency.

“Teachers have to figure out ways of helping students be successful,” Connor said.

Chamberlain High School English teacher Seth Federman has embraced that message.

Many students in the least conducive environments for learning find themselves most challenged by school during the pandemic, Federman said. It’s imperative to be mindful of their situations and not punish them for it, he said.

“My biggest goal is, are you mastering the standards?” said Federman, who served on the state’s recent language arts standards revision panel.

Federman contended that it’s become obsolete to grade students based on whether they deliver papers by a certain time, as that approach focuses more on compliance than learning. But, like Amheiser, the Meadowlawn Middle teacher, he said he needs to see at least some work that tells him how much the student knows.

“There are times I have to work with students to see what they need to show … to meet the standards,” he said.

The focus, shared by many, on completed assignments has raised questions about whether teachers are making student performance look better than it really is.

A recent study found that, while overall student performance is down from a typical year, achievement in reading has not dropped as badly as anticipated during the pandemic. The study, based on in-class assessments from hundreds of schools across the nation, was conducted by NWEA (formerly the Northwest Evaluation Association), a nonprofit organization that develops educational tests.

Karyn Lewis, a researcher with the nonprofit, noted that the results relied on students who were there, meaning those most vulnerable were less likely to be tested. Lower-income students and children of color have not returned to classrooms in the numbers that more affluent students have.

Federman and others said they have not inflated student grades this year. They’ve just issued them with more care.

“Let’s be real,” Federman said. “The stress of the pandemic does not make learning feasible. It’s hard. I can’t say grace over grades. I can’t say grades over grace. I measure mastery, and I give every kid a chance to show me mastery.”

Colleen Parker, a computer teacher at St. Petersburg High, said she’s had that same perspective for 25 years.

“I don’t give grades. People earn grades,” Parker said. “I look at learning as the most important thing.”

Every semester, some students don’t get their work done, she observed. It happens whether they’re at home or in a classroom.

“I always have kids who aren’t doing anything, even when I’m in front of them,” said Valerie Chuchman, who’s teaching chemistry classes to remote students attending Hillsborough’s Riverview High.

She puts zeroes in her online grade book to remind students where they stand if they don’t get their work done. But rarely do the zeroes remain, Chuchman said.

“It seems like as soon as I nudge them, they respond,” she said.

Chuchman saidshe has toldsome parents that the remote classes aren’t working for their kids. They haven’t learned time management skills and aren’t advancing.

That usually happens if push comes to shove, though.

“I don’t think you can put a deadline on learning,” Chuchman said.

Student engagement in classes is key

In recent days, letters have gone home to thousands of parents statewide saying their children are not doing well in online classes and encouraging them to go back to school. The reaction isn’t always positive.

Robin Milligan, a Pasco County teacher and mom, got one such letter for her high school-aged son, who is staying home because of a medical condition.

She bristled at the notion of returning him to in-person classes or letting him take required tests face-to-face, saying it would jeopardize his health. She also took issue with the idea of the state’s requirement that she sign a document saying she would keep him at home despite the school’s advice. She likened it to a waiver.

More than that, Milligan challenged the thought that her son’s grades are all on him.

She said he is smart and capable of passing his classes, but the school needs to take responsibility for such things as teachers who open online interactions only long enough to assign work, without offering instruction.

“You can’t tell me to sign a waiver if you’re not doing your part,” she said, calling on schools and the state to reconsider grade requirements this year. “Why can’t we have a gap year? Why can’t we just take care of kids?”

Connor, Hillsborough County’s chief academic officer, pointed out that options remain for students who are failing. They can try to earn their credits through makeup courses and grade enhancement programs.

He praised teachers for doing an “outstanding job” of working with students. The key moving forward, he said, is for teachers to get better at engaging students in learning — not a new concept, but more obvious now than ever.

That piece could include getting rid of graded busywork and focusing more on where students are at the end of the course.

“Our best days as a teacher (are) when a student struggles … and then breaks through,” said Reeves, the grading change advocate. “Why would we want to punish the struggle in September, when what you ought to do is reward the breakthrough in December?”

Photo: Teachers have found many students taking classes from home are struggling to pass. It’s led to a discussion about how best to issue grades, both during the pandemic and after it ends. [ MARTHA ASENCIO RHINE | Times ]