Technology, protocols, communication: Safety in South Florida schools since Parkland

Miami Herald | By Sommer Brugal and Jimena Tavel | February 14, 2023

In the months following the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland that left 17 dead and 17 more injured, legislators, school district representatives and parents pushed for immediate and sweeping changes to school safety.

Within weeks, lawmakers agreed that armed security should be on every campus. Later, then-Gov. Rick Scott signed a bill into law that raised the minimum age from 18 to 21 for buying a long gun, such as an AR-15-style rifle, established a red flag law, which allowed law enforcement officers to remove weapons from anyone who was deemed a threat, and increased funding for security at schools.

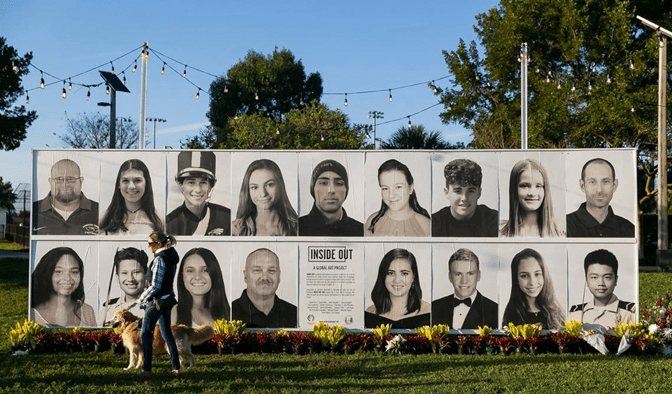

In 2020, the Legislature passed “Alyssa’s Alert,” a law requiring all public schools, including charters, to be equipped with mobile panic alert systems directly linked to law enforcement. The law, implemented in the 2021-22 school year, was named after Alyssa Alhadeff, the 14-year-old daughter of Broward School Board Chair Lori Alhadeff, one of the 17 students and educators killed in what was Florida’s deadliest school shooting.

And in the years since, South Florida school districts have enacted policies and procedures — some required by law, others put forward by their own accord — to harden, or secure, schools to hopefully prevent something similar from ever happening again.

Ahead of the fifth anniversary Tuesday of the Valentine’s Day massacre — the first observance since the confessed shooter, Nikolas Cruz, was sentenced to life in prison in November — the Herald spoke with Broward County Public Schools and Miami-Dade County Public Schools to understand those efforts and what changes are still ongoing.

In total, Miami-Dade schools has spent more than $152 million on school safety initiatives and improvements including single points of entry at all K-12 schools, routine training for staff and security, increased resources to address the mental health needs and new reporting applications and tools used to report suspicious activity.

In Broward County, it’s upwards of $70 million.

“Florida’s really a model for the rest of the country on school safety. We’re doing a lot of things that no other state is doing,” said Max Schachter, whose 14-year-old son, Alex, who loved playing trombone in the school’s band, died in the shootings.

“Schools are safer because of what we’ve done but with that said it’s going to be five years since the tragedy and you have to constantly work to prevent complacency even in Florida, even in Broward County,” noted Schachter, who created an organization to advocate for more security, Safe Schools for Alex.

NEW COMMAND CENTERS, SAFETY MECHANISMS, RESPONSES

In Miami-Dade, the district established a command center comprised of sworn and civilian officers who monitor the more than 18,000 cameras placed throughout public school campuses, according to a district spokesperson.

The center, located at the school district’s police department headquarters, oversees bus traffic, several anonymous tip reporting systems, the visitor management system and a military-grade ballistic detection system. Moreover, the district established the incident containment team, comprised of a group of officers trained to immediately respond should an event occur.

The district has also installed fencing around schools, bought additional radio equipment and mandated classroom doors be locked throughout the school day.

In Broward, the district established a safety, security and emergency preparedness division to centralize school security personnel and add new roles, including a chief safety and security officer, a director of safety operations, a director of support services and nearly 60 people who oversee daily administration and on-site management.

Within that division, the district also created an around-the-clock district security operations center that monitors surveillance cameras, manages emergency responses and detects early warning signs of a potential threat.

In January 2022, the school board approved the use of handheld metal detectors at schools and in March, former Superintendent Vickie Cartwright said schools and classrooms would be checked at random three to four times a week. (Cartwright resigned on Feb. 7, receiving a severance of nearly $268,000. Following the agreement, the school board also named Earlean Smiley, a longtime district administrator and former principal, as interim superintendent.)

Another change included the installation of auto-locking door locks in all secondary school classrooms.

Above all, the best change, according to Pinellas County Sheriff Bob Gualtieri, has been in terms of culture.

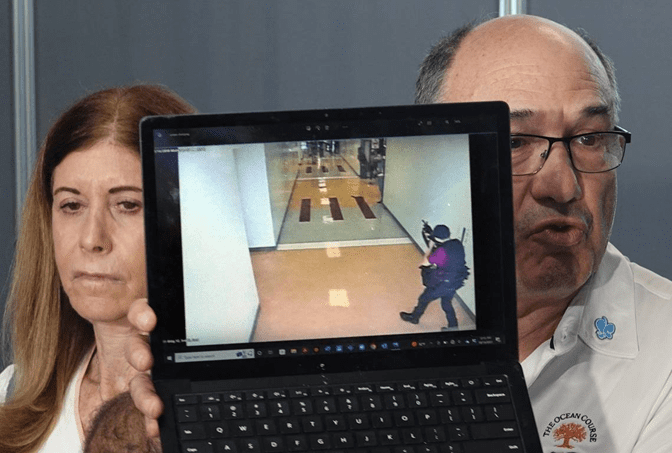

Gualtieri, the chairman of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission, has been working on school safety since 2018, pushing through eight-hour meetings and publishing reports of hundreds of pages on the topic.

“The most significant thing in the last five years is a mindset change that has taken school safety from being a non-thought — in some cases an afterthought — to the forefront,” he said. “There’s definitely been huge improvement in the recognition that the No. 1 priority in schools is not academics — it’s to make sure everybody responsible for school safety meets the expectations of the parents that when they’re sending their kids to school, they will get them back alive.”

MORE SECURITY PERSONNEL IN SCHOOLS

In Broward, officials hired more than 650 additional security staff, resulting in more than 1,300 school-focused security staff across the district, officials said. The district works with Broward Sheriff’s Office, as it does not have an in-house police department.

In Miami-Dade schools, 300 resource officers were hired following the 2018 property tax referendum, which helped fund school safety and teacher pay. To date, the district’s police department — the largest school-based police department in the country — has nearly 470 officers, according to the district.

Notably, Miami-Dade chose to place a sworn police officer in every school, officials said. The state mandate requires either a safety officer or school resource officer.

Nevertheless, both districts in December 2019 were slammed in an interim Florida grand jury report for manipulating discipline data in the School Environmental Safety Incident Reporting System, known as SESIR. In August, the full 122-page report was released, accusing five Broward County school board members of mishandling millions of dollars meant for school safety as well as neglecting their duty.

Miami-Dade, along with four other counties, including Broward, was issued a letter from the Florida Department of Education claiming it and other large districts in the state had failed to follow the state’s school safety requirements.

BETTER COMMUNICATION WITH LAW ENFORCEMENT PARTNERS, COMMUNITY

On Feb. 10, Miami-Dade County School District officials and community stakeholders, including the fire and police departments, met for the third time, according to District Police Chief Ian Silva.

The reason, he said, was to finalize a unified response that would be used in the event of a mass casualty.

In Broward, school safety officials incorporated what they refer to as a “multi-layered approach” to safety and security that involves not only school district officials and security officers, but community leaders, parents and law enforcement partners. The approach allows everyone to report what they see and enable district officials to respond.

Perhaps more importantly, though, was the district’s transition to “plain language protocols,” meaning it moved away from its longstanding use of color codes to describe and relay information regarding security events on campuses.

The problem, Toni Barnes, director of School Security Support Services in Broward County said, was that school codes used by district officials weren’t the same codes used by the hospital system or even law enforcement partners. Moving away from the color system aimed to avoid confusion and use the same standard response language. Now, instead of indicating a code red, which may indicate something different elsewhere, district officials use the term lockdown.

Officials not only made the change on campuses, but met with every single municipality in Broward County to transition them to plain language, too, she said.

For Lisa Maxwell, the executive director of the Broward Principals and Assistants Association, the school district still needs to iron out collaboration between the office of Safety, Security and Emergency Preparedness and local principals — an issue she blamed on Cartwright. Maxwell, however, did praise schools adopting after the Parkland shooting new protections like camera and buzzer mechanisms at the front entries, and developed drills and training.

“The problem is, for whatever reason, the now-former superintendent wanted to somehow blend the responsibilities of both the principals and the safety and security department. So it isn’t clear who’s in charge of campus monitors,” she told the Herald last month. “The principals’ position is either all or nothing — either we have all of the control and responsibility, or none of it because what ends up happening is you get dueling commands and supervisors.”

Ideally, she said, principals would only oversee the topic, but not directly work through it.

CONTINUOUS TRAINING

According to Barnes, “safety is everyone’s business.” That’s why the district now requires incident command systems training for school administrators, SAFE team members, safety and security staff, district leadership and the special investigative unit, she said.

“We want to make sure we’re aware of what’s going on” when law enforcement arrives and are following Homeland Security and FEMA protocols, she said.

Staff also undergoes continuous training regarding the district’s crisis communication plan and every school is equipped with the emergency protocol guides.

Similarly, in Miami-Dade, the district conducts annual emergency drills and mass casualty functional exercises at school sites and in many cases in collaboration with municipal first responders. Fire, hostage and active shooter drills are conducted monthly.

WHAT’S STILL NEEDED

Debbie Hixon, whose husband Chris died in the Parkland shooting while trying to disarm the shooter, applauded the school district’s efforts to mandate measures like single points of entry, metal wands and gated fences, but believes there’s still work to be done. She launched her career as a member of the Broward School Board after the tragedy and currently serves as its vice chair. Chris was the athletic director at the school.

“There are a lot of things that are in policy but aren’t being followed by everyone with the same fidelity, so I think that needs to be more consistent,” she said. Moreover, she’d like to see a stronger cultural shift in school districts across the country. “The culture has changed, but still needs to get better in terms of understanding we always have to be vigilant and diligent about safety.”

For his part, Gualtieri said the school districts need to track data with more accuracy and more collaboration. To that end, he wants to launch a centralized database for all Florida schools to track threat assessments. That way, if students move from Jacksonville to the Florida Keys, their records will follow them. If they’ve already shown concerning behavior and need help, all officials will know.

Gualtieri said he also wants to see a transition of power from the MSD Commission to the state’s Department of Education. In the wake of the tragedy, state lawmakers appointed the commission to investigate and recommend ways to strengthen the system. Gualtieri said in the long term, that responsibility needs to be institutionalized more directly inside the department.

Both Miami-Dade and Broward county school district officials agree that more work needs to be done.

In Miami-Dade, that looks like implementing more training opportunities for new and current employees, which could include participating in the department’s annual functional drills, Silva said. Other improvements include boosting the campus camera systems, such as increasing the number of cameras, improving the radio systems and adding wifi access in school areas. However, officials said more state funding is needed to supplement those additions.

In Broward schools, Barnes cited upgrades to technology and the district’s strong partnership with law enforcement that will support new projects in the future.

“We’re constantly training, researching [and] analyzing the best practices for safety and security, and this is going to be an everlasting change,” Barnes said. “Yes, we’re going to have projects in the coming years because we always want to be on the cutting edge of doing what we need to do to make sure all of our students are safe.”