‘That’s authoritarianism’: Florida argues school libraries are for government messaging

Public school libraries are “a forum for government speech,” not a “forum for free expression,” according to a legal brief.

Tallahassee Democrat | By Douglas Soule | December 4, 2023

Florida’s government is arguing that school districts have a First Amendment right to remove LGBTQ books.

Or any book, for that matter.

It’s a contention that First Amendment experts and advocates call extreme and chilling. But the state maintains the books on school shelves represent protected government speech. Public school libraries are “a forum for government speech,” it says, not a “forum for free expression.”

“Public-school systems, including their libraries, convey the government’s message,” Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody wrote in a legal brief.

That argument is also being made by lawyers for the school boards in Escambia and Lake counties.

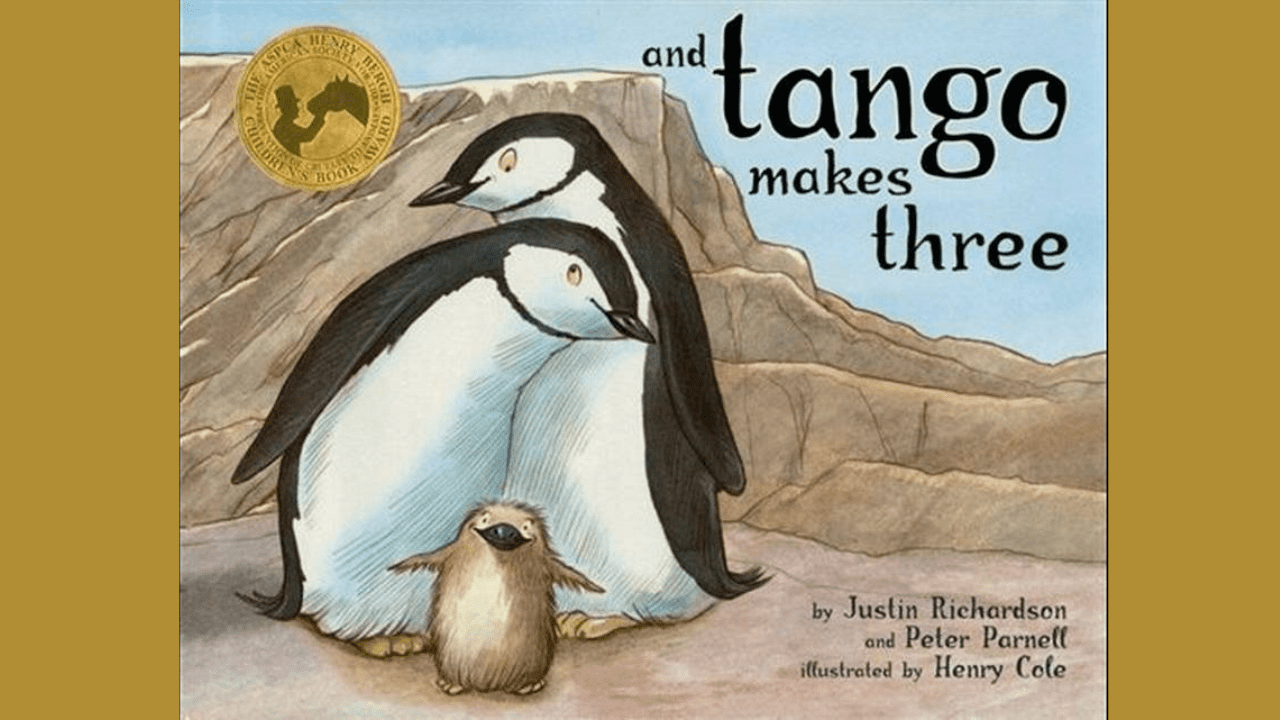

A pair of lawsuits have been filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Florida over the removal of books in both of their school libraries. Notable among those is “And Tango Makes Three,” its authors being plaintiffs.

The children’s book, based on a true story, about two male penguins raising a chick together was removed in both districts. While Lake County’s school board – which is named in one of the two lawsuits – brought the book back, Escambia County – named in both – still has it removed from school libraries.

Nonetheless, the litigation continues against both school boards.

The state was sued in one of the cases, with Education Secretary Manny Diaz Jr. and the members of the State Board of Education listed individually as defendants along with the two counties. Authors Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell are joined by a third grade student as plaintiffs in that case.

Nonetheless, the litigation continues against both school boards.

The state was sued in one of the cases, with Education Secretary Manny Diaz Jr. and the members of the State Board of Education listed individually as defendants along with the two counties. Authors Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell are joined by a third grade student as plaintiffs in that case.

“It would upend 100 years of established First Amendment precedent,” said Peter Bromberg, the associate director of EveryLibrary, a pro-library, anti-book banning organization. “This is such a far departure and would have such a ripple effect.”

Expert calls state’s argument for book removal ‘authoritarianism’

First Amendment experts and advocates interviewed by the USA TODAY NETWORK-Florida all had grave warnings about what court support for the state’s argument could mean.

“There’s considerable irony in that those who seek to limit access to books in school libraries often say they’re fighting for parental rights,” said Ken Paulson, director of the Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University. “If government speech determines what books can be in the library, the government is essentially saying your children can only see the ideas that the government has approved.

“That’s not parental rights,” he added. “That’s authoritarianism.”

Shalini Goel Agarwal, counsel for Protect Democracy, called the state’s position a “sweeping argument.”

Agarwal and her organization are representing the plaintiffs in the case against the Escambia County School Board.

“It seems to us that their position is that a school official has unfettered discretion to decide what is in the library, or what library books are taken out, and they can take them out for any reason at all, even for discriminatory reasons,” she said.

That’s exactly what the lawsuit alleges is happening.

“In every decision to remove a book, the School Board has sided with a challenger expressing openly discriminatory bases for the challenge,” the plaintiffs write. “These restrictions and removals have disproportionately targeted books by or about people of color and/or LGBTQ people.”

School book bans by state as of June 30, 2023, according to PEN America. PEN America

Over the last couple of years, Gov. Ron DeSantis and the Republican-dominated Legislature have passed laws that have led to a barrage of book restrictions and removals in schools. PEN America recently ranked Florida as the nation’s leader in book bans. That term in itself has generated controversy, with many conservatives maintaining “book banning” is a misleading exaggeration.

Still, Florida’s laws have also been met with complaints of vagueness, with school districts interpreting them in dramatically different ways. Some haven’t touched their shelves. Others, like Escambia County, have restricted or removed hundreds.

And the argument that Escambia’s actions are protected government speech, Agarwal says, would have a broader effect than just books.

Using the “government speech doctrine (in this case) would basically eviscerate a lot of other areas where people would expect the First Amendment to apply,” she said.

In her case, a group of 23 constitutional scholars from across the nation filed a brief opposing the state and counties’ government speech assertions.

“[We] write to caution the court against adopting the aggressive, unprecedented interpretation of the government speech doctrine,” they said. “The notion that such libraries exist to carry official messaging is profoundly antithetical to their nature and purpose.”

What does court precedent say?

Those interviewed by the USA TODAY NETWORK-Florida say they think and hope the defendants’ argument will get knocked down.

“It’s fundamental that no government entity can engage in viewpoint discrimination,” said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom. “That’s a basic constitutional guardrail. And those guardrails apply to governments … including school boards. And that’s really what the Supreme Court (has) said.”

In legal filings, the plaintiffs extensively point to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1982 decision in Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico. In that decision, justices ruled that school boards have “significant discretion to determine the content of their school libraries.” But it said that discretion “may not be exercised in a narrowly partisan or political manner.”

The case law doesn’t end there: “Every court that has addressed that issue … has rejected the position that libraries — including school libraries — constitute Constitution-free zones in which government officials can freely discriminate based on viewpoint,” plaintiffs write.

Despite the cited laws, those interviewed also acknowledged that, generally, there are more wild cards in the judiciary nowadays. The overturning of Roe v. Wade is one example of that.

But Paulson said “fundamental constitutional principles” against the argument are clear. He even added that further judicial scrutiny of the Pico case could end up strengthening it. That decision was a plurality opinion, “in which the court is unable to generate a single opinion that is supported by a majority of the (nine) justices,” explained scholars in a National Center for State Courts study.

Ashley Moody: ‘Compiling library materials is government speech’

Moody contends that Pico’s plurality decision has no strength, especially since it predates court findings on government speech. She points to a decision that found the selection of public park monuments was government speech as an example.

“And because compiling library materials is government speech, the First Amendment does not bar the government from curating those materials based on content and viewpoint,” she wrote.

Spokespeople for the governor’s office and the state Department of Education didn’t respond to requests for comment. But Chase Sizemore, press secretary for the state attorney general’s office, said the legal filings “speak for themselves.”

“State and county employees are responsible for deciding what materials ultimately appear on the shelves of Florida’s public-school libraries,” Sizemore wrote in an email. He also said Florida law also gives parents every opportunity for input on those matters.

“The plaintiffs in this case are arguing that third parties — the authors of the books themselves — can demand that their preferred materials be put in school libraries,” Sizemore wrote. “If that were right, it would negate not only the decisions of the responsible officials, but parental input too.”

Book removals not limited to Florida

Arguments defending book removals as protected government speech aren’t only happening in Florida.

“It’s a theory being advanced by those who would like to limit access to certain ideas or beliefs in libraries,” Caldwell-Stone said. “Not only in school libraries but public libraries as well.”

Local officials in Llano County, Texas, for example, are arguing that “content and viewpoint consideration are both inevitable and permissible when weeding books.” They’re appealing a federal court’s decision ordering them to return removed books to shelves.

In Arkansas, librarians filed suit against a law signed by Republican Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders that went after library materials. Rebuffing the state’s government speech arguments, the federal judge in July temporarily blocked key portions of the law mandating and outlining public library book challenge policies and criminalizing providing “harmful” books to minors.

“Defendants are unable to cite any legal precedent to suggest that the state may censor non-obscene materials in a public library because such censorship is a form of government speech,” U.S. District Judge Timothy Brooks wrote.

Caldwell-Stone anticipates lawsuits will emerge elsewhere, too.

“Should schools be preparing individuals to be broadly educated, to be able to make their own decisions about their lives?” she asked. “Or should schools be indoctrination centers for only one viewpoint that may not even represent the viewpoint of the majority?”