‘They feel ostracized’: Some Polk teachers say parental-rights law creates uncertainty

State: Only applies to K through third grade as of now

The Ledger | By Gary White | August 8, 2022

When Kristina Thorwegen welcomes students into her class Wednesday to start the school year, the sixth-graders might notice a magnet on her door declaring the room a safe space along with an image of a rainbow-hued heart.

Thorwegen, who teaches English language arts at Lake Alfred Polytech Academy, also plans to continue her custom of giving students an introductory questionnaire. In eight years of teaching, Thorwegen said she has learned that students have a variety of learning preferences.

On the questionnaire, Thorwegen asks students if they absorb information best by seeing it or by hearing it. She queries students to find out if they are more conceptual or tactile in their approach to learning.

And Thorwegen also asks students for their preferred names. That might mean a boy named Robert asks to be called Bobby, or — in the case of one student from the previous school year — a student with a traditional female name who wanted to be known by an unusual, gender-free name.

The questionnaire also allows students to tell Thorwegen what pronouns she should use in referring to them. She said she added that question about five years ago after a student asked to be identified in class as “they” and “them.”

Thorwegen, a Davenport resident, is ready to find out if Polk County Public Schools considers her practice at odds with a controversial law officially known as Parental Rights in Education. The law, passed this year by the Florida Legislature as a high priority of Gov. Ron DeSantis, states that public schools may not engage in classroom instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity in kindergarten through third grade “or in a manner that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.”

The law, part of a wave of legislation DeSantis promoted as a crackdown on “woke ideology” and “indoctrination” in schools, generated backlash, with critics bestowing the pejorative name “Don’t Say Gay.”

With teachers back in classrooms for the first time since the law took effect on July 1, Thorwegen and others say they face confusion and uncertainty about just what discussions teachers are now allowed to have with students, especially when youngsters approach them to share questions about their own sexuality or gender identity.

“I have teacher friends that have left the career of teaching because of this law,” said Thorwegen, 40, who identifies as LGBT. “I have some that they are just so upset about it because they feel ostracized themselves.”

One of Thorwegen’s close friends, Anita Carson, quit the profession this summer after more than a decade as a teacher, the last eight years in Polk County. Carson called the Parental Rights law the final straw in a series of perceived slights by the state’s political leaders.

Carson now works as a statewide community organizer for Equality Florida, a nonprofit that advocates for civil rights and protections for LGBTQ residents. She said she has heard from teachers who are unsure of how the Parental Rights law limits conversations with students.

“It’s very purposely vaguely written, which creates chaos and panic and fear around what we’re allowed to do without losing our jobs or losing our licenses or being sued by a parent,” Carson said.

She clarified that potential lawsuits would not necessarily target teachers but could create financial burdens for school districts already struggling over funding needs and facing staff shortages.

Florida Rep. Melony Bell, R-Fort Meade, was one of the bill’s co-sponsors. All legislators representing Polk County voted for the measure.

The Parental Rights in Education law covers more than classroom instruction on sexuality and gender identity. The seven-page legislation also specifies that parents must have access to their children’s education and health records. And it directs schools to inform parents about any changes in students’ “services or monitoring” provided to students based on mental, emotional or physical health needs.

The law also requires schools to notify parents of all health care services offered and to withhold them at a parents’ request. And it compels schools to obtain permission from parents before presenting well-being questionnaires or health screenings to younger students.

But the law has generated discussion and criticism mainly for a section intended to proscribe discussions of sexuality and gender identity. The measure specifies actions parents may take if they raise a concern that “is not resolved by a school district.”

Parents may ask the state’s commissioner of education to appoint a special magistrate to investigate the dispute, with the costs borne by the school district. Or a parent may bring legal action to seek a declaratory judgment. In such cases, a court may award damages to the parent and charge the district for attorney fees and court costs.

Memo lacks specifics

Even before the Legislature adopted the bill, critics questioned exactly how the prohibition against instruction on sexuality and gender would apply to informal classroom discussions.

The Florida Department of Education issued a memorandum to school districts, signed by Senior Chancellor Jacob Oliva, on June 6. The three-page letter mostly offers a summary of the law’s text.

In the memo, Oliva wrote that the DOE would begin “the rule development process” and that it would soon provide information on rule workshops. As of Thursday, Polk County Public Schools had not received any further details, spokesperson Kyle Kennedy said.

In the state memo, Oliva wrote that the provision on classroom instruction applies only to kindergarten through third grade. It will take effect for other grades only after the DOE “develops rules on age-appropriate and developmentally appropriate instruction,” Oliva wrote.

Carson said teachers of older grades might not find that reassuring.

“The problem is it doesn’t matter if the Department of Education says they’re only implementing K through three, the law is on the books,” she said. “The law has already been passed and was implemented starting July 1, with very little to no guidance from DOE or the state Legislature. And the K-through-three piece is still incredibly vague.”

In the absence of more specific direction from the state, some school districts have sought to clarify what the law means for teachers. Reports emerged in June that Orange County Public Schools had instructed teachers to remove LGBT “safe place” displays and photos of same-sex partners from classrooms.

The district released a memo Monday saying the law only covers classroom instruction and does not prohibit teachers from talking about same-sex partners or displaying family photos. The memo said teachers may still wear lanyards that say “ally” or “safe space.”

Orange County is one of four districts facing a lawsuit from parents, students and a nonprofit organization that seeks to block implementation of the law on free-speech grounds.

Polk County Public Schools had not issued any comprehensive guidance to teachers on the new law as of Thursday, Kennedy said.

“We’ve seen statewide — because this is part of what I do for Equality Florida — we’ve seen statewide that every district has sort of taken a different tack,” Carson said. “Some of them are ignoring it entirely and hoping that the DOE comes out with guidance, which I don’t think it’s going to happen.”

Carson said some districts are preemptively writing guidelines for teachers in hopes of averting legal liability. She said she has heard that other districts are holding training, but only for administrators and not for teachers.

The Department of Education did not respond to a question about the uncertainty some teachers say the new law has created.

Stephanie Yocum, President of the Polk Education Association, said that the union has “pretty robust anti-discrimination language” in its three contracts covering teachers and other district employees. She said she thinks the contracts prohibit the school district from telling teachers not to display photos of same-sex partners, adding that she doesn’t expect the district to do that.

Seeking clarification

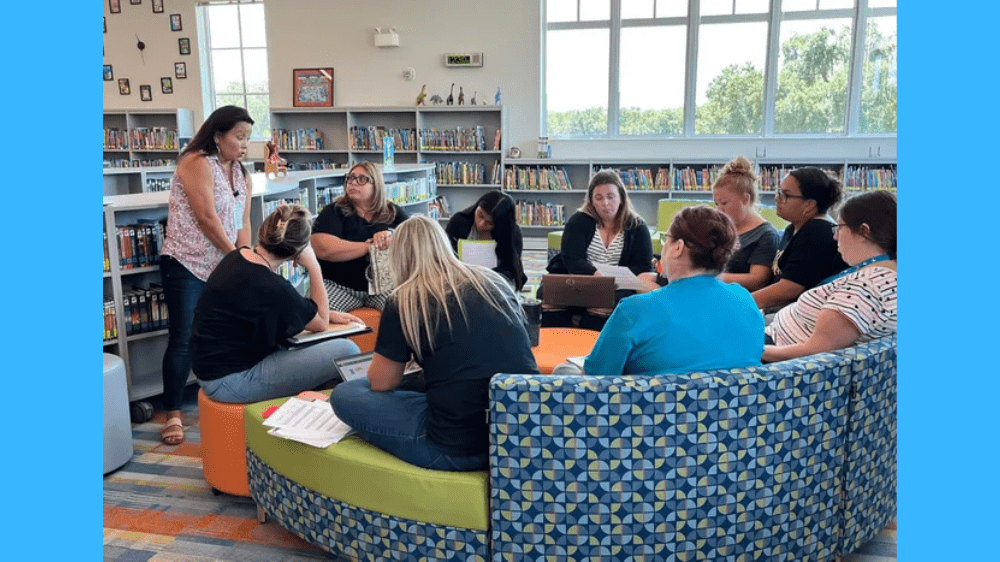

In response to teachers’ concerns, the union recently invited members to participate in a training session conducted by Safe Schools South Florida, a nonprofit organization devoted to fostering secure school environments for LGBTQ students.

The group, founded in 1991, has traditionally focused on South Florida but has recently expanded trainings to include other counties in response to the Parental Rights in Education law, Executive Director Scott Galvin said.

At least 10 teachers from Polk County took part in the video session last week, Carson said.

Galvin made it clear that his organization opposed the new law. The group held rallies, hired an airplane to fly over Miami with a banner saying “Defeat Don’t Say Gay” and arranged for students to travel to Tallahassee and protest at the state Capitol.

The training session consisted mainly of lawyers providing guidance and answering questions about the Parental Rights law. He summed up their general advice:

“If you are approached by a parent, don’t do anything that your principal doesn’t want you to do. Don’t engage; don’t fight. Don’t yell and scream, because you know that the adults who work with LGBT kids are very protected. And we don’t want somebody jeopardizing their job because their emotions are up.”

Thorwegen participated in the training session, which she said included teachers ranging from Miami-Dade County to Escambia County.

“And they were all asking things like, ‘OK, I’m a second-grade teacher, and one of my students is bullying Melinda for having two moms. What do I do?’” she said. “The guy that was running it, he was like, ‘You do what you’ve always done. You don’t allow bullying in your classroom.’”

Galvin said he doesn’t know of any school districts that have told teachers to remove photos of same-sex partners.

“This is where it’s going to get all sorts of sloppy,” he said. “Because none of the school systems put forward a unified statement, individual principals are going to start enforcing things as they see fit. … It’s just going to be a jumbled mess. How many school districts are there across the state — 60-something? So, you know, it could be interpreted 67 different ways. And even within the district, each school could look at it differently.”

Trusted adult figures

Thorwegen estimates that 30% of the students in her classes identify as LGBTQ or non-binary, meaning not entirely male or female. She said some students, even in sixth grade, have complicated gender identities.

She told of a former student whose identity varied by the day. The student came up with a strategy of wearing bracelets labeled with their preferred pronouns for the day, allowing Thorwegen to take note of the bracelet and adjust without any need for discussion.

Thorwegen said she decorates her classroom to leave no doubt that it’s an “LGBTQ-friendly” space. She said she doesn’t hide her identity but doesn’t make a statement about it either.

“It’s not something that I blatantly throw in people’s faces,” she said. “But it is something that if you are astute in any way you will pick up on the vibe of my classroom.”

She said she has never heard a complaint from a parent about her classroom displays. She recalled that once a parent asked if their child could read different lessons than the two Thorwegen had selected, covering the Stonewall uprising and the history of the LGBTQ Pride flag.

In discussing the new law, Thorwegen and Carson both raised concerns about students who are afraid to discuss questions of sexuality or gender with their parents. Carson said some students voluntarily raise those issues with teachers because the adults are trusted figures.

“When kids come to talk to me about sexuality or gender identity, most of the time it’s because they don’t have a supportive parent at home and they don’t have somebody to talk to about what they’re experiencing and their confusion about what’s going on,” Carson said. “And most of the time, my approach is to talk to them about the best way to talk to their parents.”

Carson said she has on occasion arranged to call a parent with a student during her planning period for a joint conversation.

“I would do that as long as the kid was not telling me things like, ‘My mom’s going to throw me out,’ or ‘My mom’s going to beat me,’” Carson said. “Obviously, student safety is huge there. But a lot of times, it’s just anxiety. And they need help, and they need a trusted adult that can help them through the process of being OK with themselves and getting the support they need, both in school and at their home. And I have a really hard time understanding people who see that as negative because it’s a huge part of what we do as teachers is support the kids in whatever they’re going through.”

The new law requires schools to notify parents of any changes in services or monitoring of a student related to the child’s mental, emotional or physical health. Carson said she doesn’t think that would apply to a student’s informal request to be called by a different name, though it would if the name is changed in official school records.

If a teacher recommended counseling for a student with questions about their sexuality or gender, parents would need to be informed. The law allows exceptions from parental notification if the school staff has reason to suspect the disclosure carries significant risk of neglect, abuse or abandonment by a parent.

Bell, one of the original bill’s co-sponsors, emphasized that the law focuses on classroom instruction for students in kindergarten through third grade.

“As a parent and a grandparent now, I think it’s the parents’ responsibility to have that talk with a child, and by law it says if there is any concern, that the teacher has to contact the parent to let them know if there’s any type of, that they’re inquisitive about sexual orientation or anything like that,” Bell said. “There’s some awesome teachers out there; don’t get me wrong. However, I would not want a teacher telling my child that they should transgender over to gay.”

Bell said she could understand a high school student having a private conservation about sexuality or gender with a trusted teacher but said that shouldn’t happen in lower grades.

The legislator, who was re-elected this year without opposition, said she doesn’t expect the law to generate a spate of lawsuits against Polk County Public Schools.

“I think in Polk County we’ve got a wonderful superintendent (Frederick Heid) that’s capable of handling this,” she said. “Now, throughout the state. I’m not sure about their superintendents and what will happen.”

POLK COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD RACES HEATING UP:

- Nonpartisan in name only?:Major parties endorse candidates in Polk School Board races

- District 7:Lisa Miller faces 2 challengers, in bid for 2nd term

- District 6:Newcomers Sara Jones and Justin Sharpless vie for open seat

- District 5:Pastor Terry Clark aims to deny Kay Fields a 6th term

- District 3:Rick Nolte challenges Sarah Fortney’s bid for 2nd term

- Fraud conviction:Campaign manager for 3 conservative Polk School Board candidates served prison time in Texas

- ‘A mistake’:Polk School Board candidate faces Florida Bar probe

- False campaign:Text message campaign falsely claims Polk School Board member is under criminal inquiry

Teachers now afraid?

Kim Motta, a business teacher at Union Academy Middle Magnet School in Bartow, also joined the recent video session with Safe Schools South Florida. Before that, she said, she only knew what she had heard about the Parental Rights law in media reports.

Motta, a teacher for more 20 than years, said that issues of sexuality or gender identity only arise in her classes when raised by students during mandatory anti-bullying sessions.

“Sometimes it comes up in questions,” said Motta, 55. “And now I think people are going to be afraid to say things or answer student questions that may be legitimate, age-appropriate questions because they don’t want to get in trouble.”

Motta, the mother of a teenager, said she agrees that parents should be informed about their children’s lives and educations.

Carson decried the Parental Rights in Education law as part of a campaign by DeSantis and other Florida leaders to demonize public-school teachers for political gain. She noted that teachers were rightly lauded in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, as they handled the abrupt shift to remote learning, a period when she was working 14-hour days and preparing five separate lessons a day.

“It was a massive undertaking, and it was really nice for a while there to have society and people responding positively,” she said. “And then it took a left hand turn to, ‘Teachers are indoctrinating kids,’ and ‘They’re programming them for grooming of sexual exploitation,’ and ‘They’re harming students purposely.’”

Carson said the new law reflects a false notion that teachers and parents are combatants.

“So that’s another part of the sort of vitriol around teaching right now, is there’s this lie that teachers and parents are at war with each other,” she said. “They’re not. If we do not partner with each other, it makes everyone’s job harder. Why would anyone go out of their way to make their job harder?”

Motta said she thinks the Parental Rights law adds to reasons why so many teachers are leaving the profession.

“Honestly, I don’t know that I would encourage people to go into teaching at this point,” she said.