Thousands of Teens Are Being Pushed Into Military’s Junior R.O.T.C.

New York Times | By Mike Baker, Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs and Ilana Marcus | December 11, 2022

In high schools across the country, students are being placed in military classes without electing them on their own. “The only word I can think of is ‘indoctrination,’” one parent said.

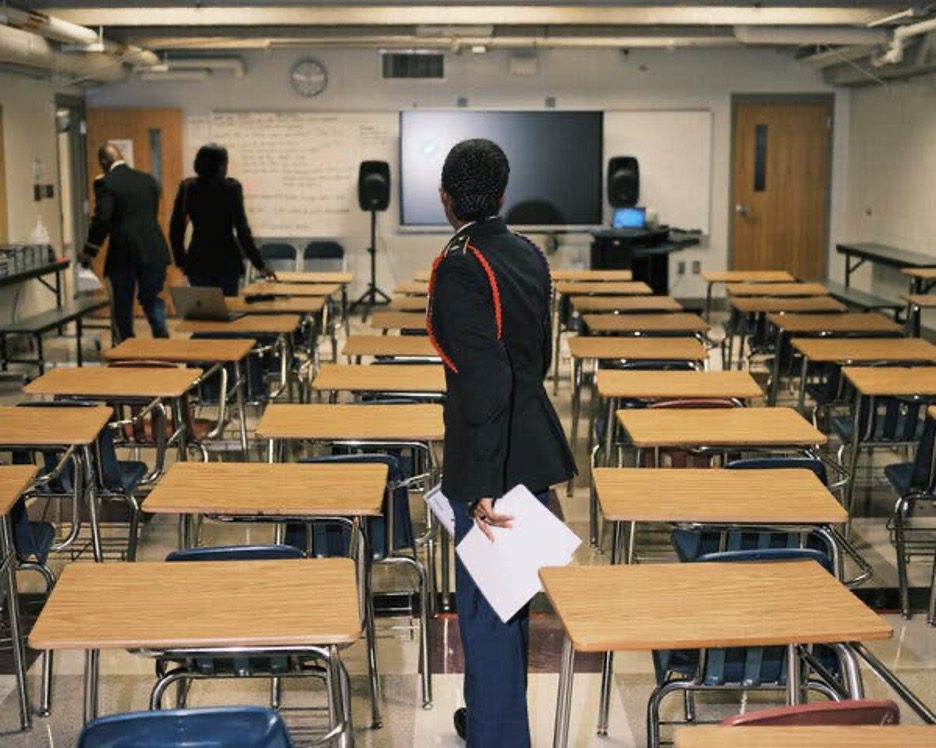

DETROIT — On her first day of high school, Andreya Thomas looked over her schedule and found that she was enrolled in a class with an unfamiliar name: J.R.O.T.C.

She and other freshmen at Pershing High School in Detroit soon learned that they had been placed into the Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, a program funded by the U.S. military designed to teach leadership skills, discipline and civic values — and open students’ eyes to the idea of a military career. In the class, students had to wear military uniforms and obey orders from an instructor who was often yelling, Ms. Thomas said, but when several of them pleaded to be allowed to drop the class, school administrators refused.

“They told us it was mandatory,” Ms. Thomas said.

J.R.O.T.C. programs, taught by military veterans at some 3,500 high schools across the country, are supposed to be elective, and the Pentagon has said that requiring students to take them goes against its guidelines. But The New York Times found that thousands of public school students were being funneled into the classes without ever having chosen them, either as an explicit requirement or by being automatically enrolled.

A review of J.R.O.T.C. enrollment data collected from more than 200 public records requests showed that dozens of schools have made the program mandatory or steered more than 75 percent of students in a single grade into the classes, including schools in Detroit, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Oklahoma City and Mobile, Ala. A vast majority of the schools with those high enrollment numbers were attended by a large proportion of nonwhite students and those from low-income households, The Times found.

The role of J.R.O.T.C. in U.S. high schools has been a point of debate since the program was founded more than a century ago. During the antiwar battles of the 1970s, protests over what was seen as an attempt to recruit high schoolers to serve in Vietnam prompted some school districts to restrict the program. Most schools gradually phased out any enrollment requirements.

But 50 years later, new conflicts are emerging as parents in some cities say their children are being forced to put on military uniforms, obey a chain of command and recite patriotic declarations in classes they never wanted to take.

In Chicago, concerns raised by activists, news coverage and an inspector general’s report led the school district to backtrack this year on automatic J.R.O.T.C. enrollments at several high schools that serve primarily lower-income neighborhoods on the city’s South and West sides. In other places, The Times found, the practice continues, with students and parents sometimes rebuffed when they fight compulsory enrollment.

“If she wanted to do it, I would have no problem with it,” said Julio Mejia, a parent in Fort Myers, Fla., who said his daughter had tried to get out of a required J.R.O.T.C. class in 2019, when she was a freshman, and was initially refused. “She has no interest in a military career. She has no interest in doing any of that stuff. The only word I can think of is ‘indoctrination.’”

J.R.O.T.C. classes, which offer instruction in a wide range of topics, including leadership, civic values, weapons handling and financial literacy, have provided the military with a valuable way to interact with teenagers at a time when it is facing its most serious recruiting challenge since the end of the Vietnam War.

While Pentagon officials have long insisted that J.R.O.T.C. is not a recruiting tool, they have openly discussed expanding the $400 million-a-year program, whose size has already tripled since the 1970s, as a way of drawing more young people into military service. The Army says 44 percent of all soldiers who entered its ranks in recent years came from a school that offered J.R.O.T.C.

High school principals who have embraced the program say it motivates students who are struggling, teaches self-discipline to disruptive students and provides those who may feel isolated with a sense of camaraderie. It has found a welcome home in rural areas where the military has deep roots but also in urban centers where educators want to divert students away from drugs or violence and toward what for many can be a promising career or a college scholarship.

And military officials point to research indicating that J.R.O.T.C. students have better attendance and graduation rates, and fewer discipline problems at school.

But critics have long contended that the program’s militaristic discipline emphasizes obedience over independence and critical thinking. The program’s textbooks, The Times found, at times falsify or downplay the failings of the U.S. government. And the program’s heavy concentration in schools with low-income and nonwhite students, some opponents said, helps propel such students into the military instead of encouraging other routes to college or jobs in the civilian economy.

“It’s hugely problematic,” said Jesús Palafox, who worked with the campaign against automatic enrollment in Chicago. Now 33, he said he had become concerned that the program was “brainwashing” students after a J.R.O.T.C. instructor at his high school approached him and urged him to join the classes and enlist in the military.

“A lot of recruitment for these programs are happening in heavy communities of color,” he said.

Schools also have a financial incentive to push students into the program. The military subsidizes instructors’ salaries while requiring schools to maintain a certain level of enrollment in order to keep the program. In states that have allowed J.R.O.T.C. to be used as an alternative graduation credit, some schools appear to have saved money by using the course as an alternative to hiring more teachers in subjects such as physical education or wellness.

Cmdr. Nicole Schwegman, a spokeswoman for the Pentagon and a former J.R.O.T.C. student herself, said that, while the program helped the armed forces by introducing teenagers to the prospect of military service, it operated under the educational branch of the military, not the recruiting arm, and aimed to help teenagers become more effective students and more responsible adults.

“It’s really about teaching kids about service, teaching them about teamwork,” Commander Schwegman said.

But she expressed concern about The Times’s findings on enrollment policies, saying that the military does not ask high schools to make J.R.O.T.C. mandatory and that schools should not be requiring students to take it.

“Just like we are an all-volunteer military, this should be a volunteer program,” she said.

Across the Country

With their uniforms in pristine condition — not a name tag out of place — a group of cadets rose in their classroom at South Atlanta High School on a recent morning to bellow a creed that vowed their commitment to family, patriotism, truth, leadership and accountability.

“I am the future of the United States of America,” the cadets said in unison.

In a school where every student qualifies for free lunch and the allure of drugs and gangs is a constant concern, South Atlanta’s longtime principal, Patricia Ford, decided several years ago to have all freshmen start in J.R.O.T.C. It was a change inspired by her brother, she said. J.R.O.T.C. had shaped him into a leader and set him on a pathway to a successful career in the U.S. Navy.

The school is less strict about enrollment than others around the country, allowing students to drop the class after they have taken some time to try it. Several cadets said they had initially resisted their placement in the program, wary of the uniforms or the intensity of the instructors, but had grown to love it. One freshman said she attempted to drop the class this year, got yelled at for trying and now says she is glad she stayed.

Several of the cadets spoke about how instructors had helped them mature into better people and pressed them to get better grades in all of their classes. Half of the students gathered on a recent morning indicated that they were considering a future in the military.

Parents, Dr. Ford said, have welcomed the class with little objection.

But in some cases, parents who discovered that their children had been enrolled in military-sponsored training have struggled to pull them out of the classes.

Mr. Mejia, whose daughter was put against her will into a class in Fort Myers, met with a series of school officials while trying to get his daughter out. He said he supported the military — his sister is in the Navy — but was outraged that his daughter was being forced into the program.

The school let his daughter out of the class, he said, only after he complained that an instructor had grabbed her by the shoulders during an exercise, an incident school officials did not dispute when they noted in a response to The Times that they had ultimately allowed the girl to drop the class.

A school district spokesman said that seven high schools in Lee County automatically enrolled students in J.R.O.T.C. but that those who objected could change their schedules.

The program has always been heavily represented in regions like Texas and the Southeast, where the military has deeper roots and military families often proudly span generations. But, even there, data released in response to federal, state and local public records requests showed that some schools had relatively small enrollments in J.R.O.T.C.

Hillsborough County, Fla., for example, has made a major commitment to J.R.O.T.C., with a program at every one of its high schools. But without enrollment mandates, the district averaged about 8 percent of freshmen enrolled last year.

On the other hand, The Times’s review found a number of high schools where at least three-quarters of a grade’s students were enrolled in J.R.O.T.C., including in Baton Rouge, La.; Cape Coral, Fla.; Charlotte, N.C.; Memphis; Port Gibson, Miss.; San Diego; Spring, Texas; and Vincent, Ala.

Many other schools have more than half of all students in some grades enrolled in the program, including some in Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, Dallas, Houston, Miami, St. Louis and Washington, D.C.

In analyzing data released by the Army, The Times found that among schools where at least three-quarters of freshmen were enrolled in J.R.O.T.C., over 80 percent of them had a student body composed primarily of Black or Hispanic students. That was a higher rate than other J.R.O.T.C. schools (over 50 percent of them had such a makeup) and U.S. high schools without J.R.O.T.C. programs (about 30 percent).

For some districts examined by The Times, it was difficult to discern whether a school required J.R.O.T.C. or if some other reason had led a large percentage of its freshmen to enroll in the program.

In Detroit, where Ms. Thomas said she had been forced to take the class, the district said in a statement that administrators did not require students to take J.R.O.T.C. although they “do encourage students in ninth grade to take the course to spark their interest.” But two recent students at Pershing, in addition to Ms. Thomas, said in interviews that they had been required to take the class. District data showed that 90 percent of freshmen were enrolled in J.R.O.T.C. during the 2021-22 school year.

Three other Detroit high schools also enrolled more than 75 percent of their freshmen in the class, according to district data.

School district officials gave various explanations for why they were putting a large proportion of their students into J.R.O.T.C.

In Pike County, Ala., which automatically enrolls all freshmen in J.R.O.T.C., administrators said the program’s focus on character and leadership had helped students improve their study habits and increase their involvement in other school programs.

“All in all, it seems to be a very positive thing that we’ve got right now,” said Jeremy Knox, who leads the district’s career education programs.

In Philadelphia, a district spokeswoman said that one school in the district, Martin Luther King High School, automatically enrolled all freshmen into J.R.O.T.C. to expose them to possible military careers and “to create a culture of teamwork, collaboration and discipline.” Star Spencer High School in Oklahoma City said it placed all freshmen in J.R.O.T.C. at the start of the school year in part because of a shortage of physical education teachers.

The principal of McKinley Technology High School in Washington, D.C., said students were automatically enrolled in the class so that they could learn leadership and discipline, though some did not take the course because of religious beliefs or opposition to the military.

Nearby, at Surrattsville High School in Clinton, Md., about 50 percent of freshmen were in J.R.O.T.C. last year. Katrina Lamont, the principal, said the school had been placing students in the program when they had not chosen other electives or needed to fill out their schedules. But doing so created a problem, she said, when students who had dreadlocks or other longer hairstyles ran up against the program’s strict grooming requirements. She said the school was seeking to be more accommodating this year.

Conflicts in Classrooms

Forcing students into J.R.O.T.C. has at times created problems with discipline and morale.

William White, a retired Army major who taught for years as a J.R.O.T.C. instructor in three states, said he found during his time in Florida that there was a constant emphasis on keeping enrollment elevated, with students required to take the class even when they were so opposed to it that they refused to do the work.

Mr. White recalled two students who had religious objections complaining to him about having to take the class.

“Kids were forced into the program,” he said, adding that he faced blowback after trying to get students removed who did not want to be there.

Marvin Anderson, a retired lieutenant colonel in the Army who is the senior J.R.O.T.C. instructor at Green Oaks Performing Arts Academy, a public high school in Shreveport, La., said students were required to take the program in their freshman year to fulfill a physical education credit, and in their sophomore year to fulfill a health credit. He said the program provided valuable training in leadership, community service and discipline. But that many students do not want to be in the class makes it difficult to maintain those values, he said.

“I have issues with behavior, and issues with grooming requirements and other things,” Colonel Anderson said. He said he struggled constantly to maintain a structured class “for teenagers who don’t want to be in the program.”

The program has also led to pushback from civilian teachers, some of whom have been uncomfortable with military posters and recruiters on campus and the curriculum taught in J.R.O.T.C. classes.

Of the textbooks obtained and examined by The Times, one from the Navy states that a U.S. military victory in Vietnam was hindered by the restrictions political leaders had placed on the tactics the military could use. That hawkish interpretation of the war fails to account for the fundamental problem that many civilian textbooks point out: the lack of popular support among South Vietnamese for their government, which was America’s chief ally in the war.

A Marine Corps textbook describing the “Trail of Tears” during the 1830s fails to mention that thousands of people died when Native Americans were forced from their lands in the southeastern United States.

Sylvia McGauley, a former high school history teacher in Troutdale, Ore., said she was troubled when she found that the J.R.O.T.C. textbooks being used at her school were teaching “militarism, not critical thinking.”

“The version of history that I was hearing from my J.R.O.T.C. kids was quite different from the versions of history that I tried to teach in my classroom,” she said.

Community Debate

Schools that have faced questions over mandatory or automatic enrollments have often responded by backing away from the requirements, as Chicago did last year.

In that case, which came to light after an article from the education news website Chalkbeat, an investigation by the school district’s inspector general found that 100 percent of freshmen had been enrolled in J.R.O.T.C. at four high schools that served primarily low-income students on the city’s South and West sides.

It was “a clear sign the program was not voluntary,” the report said.

At many schools, it said, freshman enrollment in J.R.O.T.C. “often operated like a prechecked box: students were automatically placed in J.R.O.T.C. and they had to get themselves removed from it if they did not want it. Sometimes this was possible; sometimes it was not.”

The district said in response that it was updating its parental consent process and making sure students had a choice between enrolling in J.R.O.T.C. or other, nonmilitary physical education classes.

The Buffalo school district agreed in 2005 to ensure that the program was optional after the New York Civil Liberties Union had raised questions.

In 2008, parents and other residents in San Diego confronted school district officials over concerns about forced enrollment, and won what they believed was a promise by the district to ensure that the program would be strictly optional. They also worked to eliminate J.R.O.T.C. air rifle programs in the schools.

But The Times’s review of data provided by the school district found that there continued to be schools with high J.R.O.T.C. numbers, with 77 percent of freshmen enrolled in the program at Kearny School of Biomedical Science and Technology last year. A district spokeswoman said that the data the district had provided had “some inaccuracies” but over the past several weeks did not provide new enrollment numbers and would not comment further.

“It’s almost like trying to kill a vampire,” said Rick Jahnkow, who has worked for three decades to oppose military recruitment in San Diego’s schools. “You think that you dispensed with it, and it keeps coming back.”

In some cases, students who at first balked at being forced to enroll in the program said they had ended up embracing it.

Azaria Terrell, a schoolmate of Ms. Thomas’s in Detroit, said she had changed her mind as she had begun to bond with her classmates and to heed some of her instructor’s lessons on leadership and honesty. After her required stint during her freshman year, she stayed in the program for three more years — by choice — and earned a position as the unit’s battalion commander.

“I found myself becoming a better person,” said Ms. Terrell, who ended up going to college instead of joining the military.

Ms. Thomas, on the other hand, said she had never learned to like the class and had often skipped it. When she received a failing grade, she was put back in the class for her sophomore year.

Ms. Thomas said she and other students who had been forced into J.R.O.T.C. often heard from recruiters who pitched the idea of signing up for the military in order to get help paying for college. One of Ms. Thomas’s classmates joined the military, and Ms. Thomas filled out initial recruiting paperwork one day, lured by the promises of the recruiters who had visited the school. But she was never serious, she said, and ultimately stuck with her plan to pursue a civilian career in health care.

Ms. Thomas, now a freshman in college, said she no longer responded to the recruiter, though she still heard from him.

“He still texts me to this day,” she said.

Schools With J.R.O.T.C. Enrollment of at Least 75% in Certain Grades

Alabama

Lanett City School District: Lanett High School; Mobile County Public Schools: Blount High School, LeFlore Magnet High School, Rain High School, Vigor High School, Williamson High School; Pike County Schools: Goshen High School, Pike County High School; Shelby County Schools: Vincent Middle High School

California

Los Angeles Unified: Los Angeles Senior High; San Diego Unified School District: Kearny Biomedical Science and Technology

Florida

Lee County Schools: Ida S. Baker High, Lehigh Senior High, Mariner High, Riverdale High; Polk County Schools: Ridge Community High

Georgia

Atlanta: B.E.S.T. Academy

Illinois

Chicago Public Schools: Bowen High School, Clark High School, Fenger High School, Harlan High School, Manley High School, Spry High School

Louisiana

Caddo Parish: Green Oaks, Woodlawn; East Baton Rouge: Belaire High School, Northeast High School

Michigan

Detroit Public Schools: Communication and Media Arts High School, Denby High School, Detroit Collegiate Preparatory High School at Northwestern, Pershing High School

North Carolina

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools: Hawthorne Academy

Oklahoma

Oklahoma City: Star Spencer High School

Pennsylvania

Philadelphia: Martin Luther King High School

Tennessee

Memphis-Shelby County Schools: Hamilton High

Texas

Fort Worth Independent School District: Young Mens Leadership Academy; Spring Independent School District: Spring High School 9th Grade Center