Universal School Vouchers: How much and who’s paying?

Charlotte County Florida Weekly | By Laura Tichy | April 6, 2023

The price tag for school vouchers draws a variety of estimates, and in Arizona, where similar law was enacted, the governor says the program could bankrupt the state.

While HB 1, Florida’s universal school vouchers bill, made its short legislative journey from being passed by the House on March 17 to its equivalent bill being passed by the Senate on March 23 to Gov. DeSantis signing it into law in a ceremony at a private Catholic school in Miami on March 27, questions hung in the air about the how much it would cost.

Estimates varied wildly, from the House’s estimate of $209.6 million to the Senate’s Education Appropriations Committee acknowledgement that the cost was indeterminate.

Outside analyses varied from a $2.8 billion general appropriations budgetary impact made by the Florida Education Association to the $4.06 billion estimated by the Florida Policy Institute to account for the full impact to taxpayers and schools.

Why do these costs estimates vary so much?

Part of the variance is based upon differences of opinion as to how many parents of newly eligible students will choose to apply for the money. Part is based upon defining exactly whom will have to foot the bill for the program, which provides the opportunity to present the accounting in different ways. And beyond the questions of how much and to whom it will cost, the law prompts new questions about whom the vouchers will truly benefit and what safeguards will be placed to ensure parents actually spend the money for the intended purpose — children’s legitimate educational expenses.

“What they’re doing behind closed doors on trying to figure out where this money is going to come from, they need to take it from unallocated state resources,” said former Florida Education Commissioner Betty Castor. Now a member of the Florida Leadership Council, Ms. Castor served in the cabinets of both Republican Gov. Robert Martinez and Democrat Gov. Lawton Chiles in the 1980s and ’90s.

“We have a lot of money in the state of Florida, so if this is such a number one priority, they ought to go and take it from new money, not from the money that is going to our strapped public schools,” Ms. Castor said. “They can’t even pay their teachers. We’re still at the lowest of the low states — it’s just mind boggling. The Florida Policy Institute — and I certainly agree with it — has recommended that they hold school districts harmless. That would essentially mean that they not take money away from the school districts based on all of these questionable assumptions and not knowing what the impact could be with this. I would call it just a dramatic change in the way we fund education.”

To understand the newly expanded program, it’s necessary to understand the main types of voucher scholarships and their equivalents, as well as their funding sources, as they exist during this current 2022-2023 school year. Florida currently offers the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship (FTC), the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Educational Options (FES-EO) and the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA), with the last one delivered to parents as an education savings account (ESA) on the premise that it makes it easier for parents to pay for therapies their children with disabilities need in order to learn.

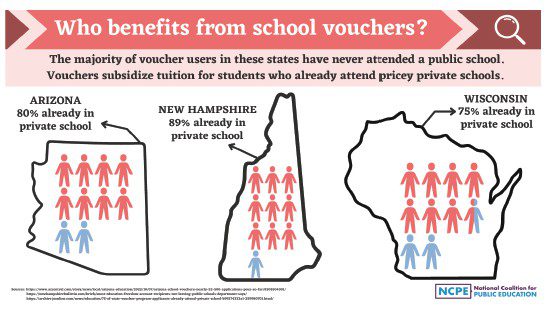

Studies in other states found that the majority of voucher users were already enrolled in private schools. SOURCE: NATIONAL COALITION FOR PUBLIC EDUCATION

The state’s Department of Education assigns management of the scholarships to nonprofit concessionaires called scholarship funding organizations (SFO). Florida contracts with two, with the larger being Step Up for Students.

The FTC is a program where corporations may make voluntary contributions to an SFO in return for dollar-for-dollar tax credits. The contributions are awarded as $7,400 scholarships paid to private schools to benefit low-income students (defined as below 400% of federal poverty level) or foster children. The program serves 97,870 students currently. The contribution credits potentially impact average taxpayers because the corporations would have otherwise paid the money as taxes that enter the state budget. The reliability of the funding year-to-year can be affected by economic impacts to the corporations.

The FES-EO program is funded from the Florida Education Finance Program (FEFP), which is the state’s portion of funding towards local public school districts’ budgets. It offers similar scholarship funding and has qualifications similar to the FTC, with the addition that children of military or law enforcement or siblings of children receiving the Unique Abilities scholarship also qualify. The FES-EO once required that a child had originally been enrolled in a public school, which meant there was funding allotted for that pupil, but that requirement was removed in recent years. The program currently serves 88,114 students.

About 80% of Florida’s students already qualified for these scholarships in 2022-2023. However, in the House PreK- 12 Appropriations Subcommittee meeting on Feb. 23, committee vice-chair Rep. Kaylee Tuck said that both the FTC and the FES-EO were significantly underutilized by eligible students this school year. The FTC has a $400 million surplus, and the FES-EO has space for an additional 55,000 students. So, why expand eligibility if the current programs are already underenrolled?

“Some of the early (legislative) sessions where they were presenting, there’s no demand for these vouchers amongst the people who make $100,000 or less,” said Dr. Sue Woltanski. A retired pediatrician, Dr. Woltanski has blogged for a decade about education advocacy as Accountabaloney.com, and she has served on the board of the Monroe County School District since 2018. She spoke to Florida Weekly representing her own viewpoints as an education advocate, not those of her school board.

This year’s $7,400 scholarships, and even the $8,700 projected for next year with the new legislation, fall short of the $9,873 that website Private School Review shows as the average tuition for Florida private schools. That difference is difficult for families to scrape up if the reason their children are able to eat twice a day is because of free and reduced-price school meals, one of the overlooked wraparound services that public schools provide.

Also, a student first must be accepted to a private school; unlike public schools, the private ones don’t have to accept everyone (as is also the case with charter schools). While private and charter schools often have the cachet of providing a higher-quality education, some researchers question if this perception of higher quality may be due, in part, to these schools simply having the opportunity to cherry-pick the higher performing pupils.

Additionally, since FTC and FES-EO currently are true scholarship vouchers — with the payments sent directly to the private schools — and many of the elite private schools currently do not accept them, this may also contribute to the current under-enrollment in the programs.

“People (whose children) are currently in public school are not knocking on the door trying to get money for vouchers, for the most part,” Dr. Woltanski said. “There’s no waiting list, and it’s really unusual for them (legislators) to admit they have no waiting list because that has always been the thing that drove the expansions before. The reason they’re doing this is to give money to people who are already in private school.”

No longer vouchers under the new law

An important distinction to understand is that the funds are no longer provided as vouchers under the new law. Along with removing the income cap and other restrictions from both FTC and FES-EO, the money will be deposited into ESAs, like how the funds for the Unique Abilities scholarships have been handled, managed by an SFO.

This means that if a private school doesn’t accept the money for tuition or if parents have no difficulty affording tuition, the parents can spend the money on other education-related expenses. It also frees the money for use for homeschoolers since it is no longer paid directly to a private school.

While proponents say this provides maximum educational choice through customization, critics say the system provides potential for inefficiencies, waste or fraud.

Dr. Woltanski wrote on her blog that Unique Abilities scholarship parents have complained that the eCommerce section of Step Up for Students’ current website makes it easier to purchase video game systems with the scholarship money than to obtain specialized therapies for their children’s disabilities, and soon, the website will have to accommodate potentially hundreds of thousands of new users.

Once the nonprofit begins administering the new accounts, FPI predicts there will be so many children using the ESAs that they will create a new school “district” larger than the enrollment in Hillsborough County Public Schools, nearly 219,000 students. Step Up for Students would be the de facto unelected school board.

So, just how many parents of newly qualified students might apply? Although it sounds like a simple question, differing speculations are part of why the cost estimates have varied so widely.

Florida currently has about 292,000 students without vouchers enrolled in private schools. Additionally, the state has about 114,000 homeschooled children. Together, these amount to 406,000 potential new applicants. And then there are a number of students currently attending public schools who might switch next year now that qualifications such as the income cap have been removed.

The House’s estimate of $209.6 million started with only the nonvoucher students attending schools that currently take vouchers, not accounting for the potential that some of the schools previously refusing to accept vouchers might begin to do so now that their existing students have become eligible. Then, the legislators assumed that only 50% of those newly eligible parents with children in the current voucher-accepting schools would apply, so the House estimated that the state need only budget for 24,535 additional students.

Their assumption ignores that with the transformation to ESAs, the money could be spent on educational items and services other than tuition. It also ignores the potential, with public funding now available, that private schools might decide to raise tuition, which could prompt more parents to apply.

The FEA’s $2.8 billion estimate assumed that the state should prepare for the potential of all of the newly eligible private and homeschool students to apply.

The Florida Policy Institute’s calculation of $4.06 billion is more complex because it includes $1.1 billion for students currently receiving FES-EO and -UA scholarships, which the legislature ignored because it already exists in the budget; estimates $890 million for about another 104,500 of Florida’s 2.9 million public school students who are statistically likely to transfer once the income cap is lifted; and estimates $1.1 billion for newly eligible private school students and another $971 million for homeschool students, both calculated on the assumption that 75% of those eligible will apply.

The FPI didn’t choose a 75% application rate at random; Arizona preceded Florida by a few months as the first state to expand to universal ESA eligibility, with the program having started in October 2022. Prior to expansion, the program had only 11,800 students. Legislators assumed few parents would apply and only budgeted $30 million at an average award of $7,000 to cover the ESA expansion for the entire year.

But so many parents applied that the program had already overrun its budget by $200 million by January 2023. As of March 27, 50,718 students now have ESAs, and more are in the process of applying at a rate that will approach 75% of Arizona’s newly eligible private and homeschooled students by the end of the fiscal year.

The Arizona Joint Legislative Budget Committee stated, “Our best guess is that universal enrollment will be 52,500 in fiscal year 2024 at a cost of $376 million.” Katie Hobbs, Arizona’s new governor, said in her State of the State address that the scholarship expansion threatens to bankrupt the state, and she has called for the Legislature to roll back eligibility to the pre-2022 requirements.

“The Legislature completely failed to appropriate for this because they didn’t think it would be as widely used as it’s being utilized right now,” said Beth Lewis, director of Save Our Schools Arizona. “The reason for that is because the vast majority of kids are already in wealthy private schools and homeschooling situations, so there was no money allocated to those children to start with, and the Legislature failed to appropriate any new funding for these kids. And I don’t know how this will play out in Florida, but we’ve got all of these homeschoolers who are grabbing the money, and they’re spending these millions of dollars to build playgrounds in every single backyard instead of building up a playground for the local public school. They’re just wiping taxpayer dollars out all over the place. It is the least efficient use of public money I’ve ever seen.

“You can’t fund multiple separate systems and expect to get a higher return on your dollar. For anybody who is concerned about the cost to the state, if your state is funding an entire public system, an entire private system, an entire charter system and potentially an entire homeschool system, your taxes will go up. That is a certainty.”

How it will be funded

The reason Florida legislators didn’t have to finalize the funding for the universal vouchers bill prior to passing it is because such budgetary matters get hashed out separately in the general appropriations bills.

HB 5101, the House appropriations bill for education, was announced on March 22. The bill proposes changing how the Florida Education Finance Program, or FEFP, formula is calculated, which is the state’s portion of funding toward the school districts’ budgets. The FEFP includes a base allotment per student that comprises over 60% of the money, and then it includes protected money earmarked for certain programs mandated by statute, such as transportation, called categoricals.

HB 5101 proposes to collapse many of the categoricals into the base student allotment, including the allocations for instructional materials, mental health, reading, safe schools, teacher salary increases and classroom supply assistance. A press release issued March 22 by the House Office of Public Information touted this change as beneficial to schools by allowing school districts greater flexibility to tweak funding to their local needs by freeing up $1.8 billion in categoricals funding plus adding $805.7 million in new funding (for a total of $2.1 billion). In a meeting of the House PreK-12 Appropriations Subcommittee on Jan. 4, the discussion was about revising the FEFP formula to fund school choice scholarships, to include a PowerPoint slide that stated that “Categoricals are the biggest challenge to funding ‘choice’ in the FEFP.”

As the subcommittee chair’s staff didn’t respond to Florida Weekly’s multiple requests for an interview, we have only Rep. Josie Tomkow’s comments from the meeting video recording to report — which shows the seeds for funding were planted three months ago: “While the overall structure and components of the FEFP have not significantly changed in the past 50 years, what has changed is our state’s expansion of school choice,” she said, “and in particular, nonpublic school choice funded in the FEFP. For our state to continue to advance the policy of education based on parental choice, the FEFP may need to be revamped to align with this policy. In potentially revamping the FEFP, the categoricals funded in the FEFP may also need to be reviewed.”

The FEFP was developed in the 1970s as a way to equalize education between the counties that have a significant tax base and the counties that are unable to collect as much in taxes to fund their school districts, with earmarked funding as categoricals added over the years as mandated statutes were passed.

As an example of how this works, Dr. Woltanski said her school district in the Florida Keys has the unusual combination of having only 9,000 students enrolled but having a high tax base because of the property values on the islands. As a result, only 10% of the school district’s budget comes from the state FEFP. After the FES students were mandated two years ago to be funded through the local districts’ FEFP funds, the voucher scholarships for the 253 FES students in her district this school year took up 43% of the state FEFP funds that the Monroe County School District received.

Dr. Woltanski said that between a Catholic school expansion taking place in Key West and homeschoolers, her district could add an additional 500 FES students. That could fully absorb the state FEFP portion of the district’s budget. And then what happens if the FEFP money isn’t enough to pay for all of the students?

In its education budgets, the House has budgeted $1.87 billion for FES scholarships with an additional $109 million set aside in case more students than expected apply. The Senate has budgeted $2.2 billion for FES scholarships with a $350 million runover set aside. But a more significant difference is that the House includes the scholarships in the FEFP budget whereas the Senate places the scholarships on their own budget line separate from the money budgeted for the school districts. This both reduces possible impacts upon the school district budgets by keeping the scholarship funding separate as well as provides more transparency for tracking the scholarships than when they are folded into the districts’ budgets.

Politicians favor catchy slogans such as “fund children, not schools” and “funding follows the child,” but education advocates point out that for children who have never attended public schools, they have no pre-existing funding from the public school district to simply follow them to their next educational endeavor. Politicians also imply that well-off private school and homeschool families deserve public scholarship vouchers because they receive nothing of value for their tax dollars supporting public schools since they choose nonpublic schooling for their children. Curiously, no politician seems to have followed that rhetoric to its logical conclusion of proposing a $8,700 property tax rebate to people who have no children to school either publicly or privately, such as Florida’s millions of retired homeowners.

“They have been ginning up this idea that (private school parents) pay taxes but get nothing for it,” Dr. Woltanski said. “It’s like, no, you get public school (from paying your taxes) so that kids aren’t stupid so that — when you get old — the nurse calculating your IV drip knows math.”