What a Florida man’s school shooting database can tell us about gun violence on campuses

Florida Today | By Finch Walker | May 26, 2022

While gun violence in schools has been an issue since at least the 1970s, it was only within the past few years that information about shootings was compiled in a database.

David Riedman, 37, of Titusville, a graduate of the Naval Postgraduate School and current PhD student at University of Central Florida, created the K-12 School Shooting Database following the Parkland shooting, where users can view information about every incident involving a gun at a school in the United States since 1970.

Developing the database

In 2018, Riedman was involved in the Homeland Security Advanced Thinking Program at the Naval Postgraduate School, which he described as a “think tank around emerging homeland security issues.”

While he was there, 19-year-old Nikolas Cruz killed 17 people and injured another 17 at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland Feb. 14, 2018. His trial is underway in Fort Lauderdale in Broward Circuit Court.

Following that mass shooting, Riedman’s goal was to find better strategies for conducting threat assessments and to find out what red flags may have been missed.

He and his colleague, Desmond O’Neill, found there was a lack of data compiled in one place on school shootings. They began the tedious process of collecting data on their own and putting it in a Google spreadsheet for their own research.

They soon realized the value in what they’d created.

“After a couple of months, we realized that we had created a unique resource that didn’t exist,” Riedman said.

The spreadsheet sparked the idea to make a database, but it wasn’t an easy process.

The two spent months extensively searching newspaper archives to collect data on school shootings back to 1970. Their research didn’t just encompass mass shootings, but covered any time a gun was fired on school property.

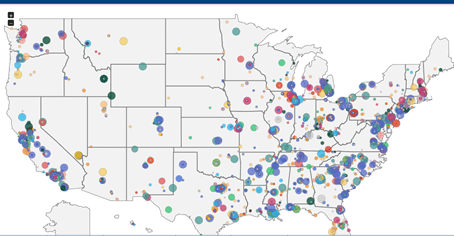

Now, the K-12 Shooting Database is available on the Center for Homeland Defense and Security’s website as a tool for information on every school shooting across the country, including the number of fatalities and injuries in a shooting, the age of the shooter, what time a shooting occurred and a brief summary of the shooting.

Data Map – K-12 School Shooting Database

What the data shows

The information on the database has been referenced by numerous studies and groups.

It’s been cited by about 60 peer-reviewed publications, the Government Accountability Office, Congressional Research Service and the presidential commission established after the Parkland shooting in its report to Congress on school safety.

Reidman said he’s noticed a few specific points as he’s spent years immersed in the data.

Planned attacks at schools are not new and have been happening for decades, Riedman said. There have been eight other “significant attacks” against elementary schools other than the Sandy Hook school shooting in Connecticut in December 2012.

“They’ve occurred back to the 1970s,” he said. “This is not a problem that is new. It’s not a problem that relates to the internet or social media or violent video games or violent movies … it’s a much deeper, generational issue.”

Mass shootings, which involve at least four fatalities, get a lot of attention. Other serious shootings often do not if there aren’t many fatalities, despite the number of injuries suffered during the incident, Riedman said.

An attack similar to the one that occurred Tuesday in Uvalde, Texas — in which an 18-year-old gunman killed 19 children and two teachers —. almost took place several weeks ago in Washington, D.C., Riedman said.

A sniper positioned himself on the sixth floor of an apartment building across from Edmund Burke School with six automatic rifles and 1,000 rounds of ammunition. He fired 230 shots, wounding four people, before taking his own life.

“He was a terrible shot,” Riedman said. “But that had the potential to be an incident that had dozens killed.”

Riedman said his data shows incidents like the one in Washington, D.C., happen all the time, where serious attacks are “narrowly averted.”

Because these attacks are avoided, they don’t gain the attention that major shootings do.

“If we could see the types of gun violence that’s occurring in schools, kind of week in and week out, there might be more attention and commitment to making meaningful steps to solve this problem,” he said.

“If we could see those warning signs, understand those incidents, and kind of galvanize our national attention toward some kind of preventative measures, we wouldn’t have to be here again today.”

Riedman said his data shows there’s systemic gun violence on campuses that has gotten “significantly worse” since the pandemic. It involves disputes among students who are armed without the intent to attack. However, the disputes escalate, and a shooting occurs.

Unlike planned attacks, these shootings were not happening over approximately 50 years of data, Riedman said.

“That type of systemic gun violence is an entirely new challenge that schools really need to deal with,” he said.

At this point, it’s too early to tell why a spike in systemic gun violence has occurred following the pandemic, Riedman said.

Taking preventative measures

Every time a shooting happens at a school, Riedman manually enters it into the database.

So far, there have been 137 school shootings in 2022. Of those, 135 were non-active shooters, meaning they were isolated fights or disputes.

“It’s just tragic that the same thing plays out over and over,” Riedman said.

Riedman said he hopes preventative measures can be put in place, such as making sure people in crisis get the help they need and mental health problems don’t fester for years untreated.

“It’s not somebody that just snaps one day and decides to commit a mass shooting,” he said. “Mass shooters are people that have months and years of trauma, violence, depression, suicide, self-harm, and their behavior escalates as they continue to degrade, and then an attack occurs,” he said.