What Makes for an Effective Secretary of Education?

Thick skin, respect for data are among the qualities needed for success

Education Next | by Frederick Hess | November 23, 2020

In D.C. education circles, President-elect Biden’s electoral victory has spawned a hot new guessing game: Who will be the next secretary of education? I’ll tell you upfront, I have no idea. And, this year in particular, I can assure you that the Biden transition team doesn’t much care what I think.

I will offer one insight, for what it’s worth. It’s pretty clear that any Biden nominee is going to require the backing of the NEA and AFT. Meanwhile, assuming Republicans claim at least one of the two Georgia Senate seats (and that’s the way to bet), any nominee is also going to require some GOP support. Although bipartisan support for a secretary of education-designee was once a norm, Democrats voted unanimously against Betsy DeVos in 2017—setting a new precedent. The upshot is that the eventual nominee will have to fit a relatively narrow political window (which could yield some surprising developments).

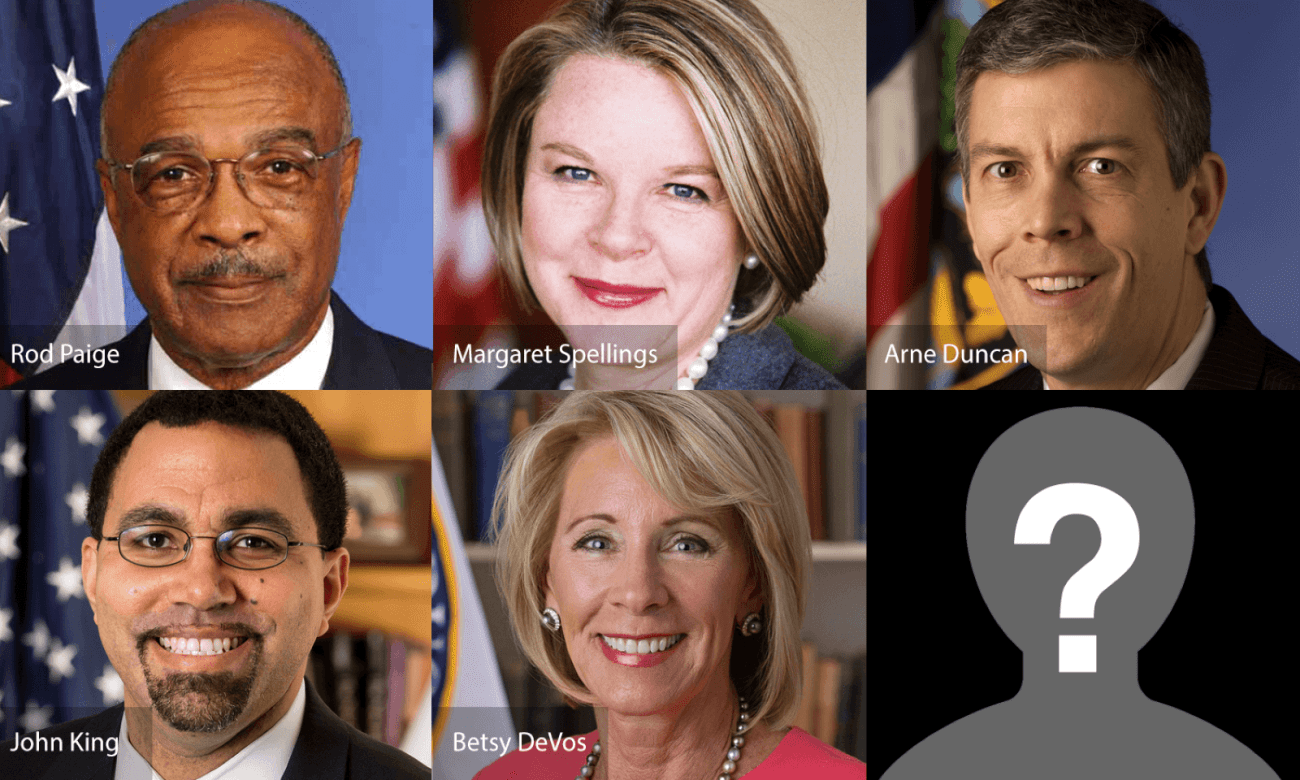

But, rather than talk politics or prognostication, I want to focus on something else here. As I noted over at Forbes the other day, I’ve enjoyed a front-row seat for the tenures of the past five secretaries of education—from Rod Paige to DeVos. I’ve had the opportunity to observe their strengths, limitations, and experiences, and I’ve concluded there are a half-dozen traits that President-elect Biden should seek in his choice:

A willingness to put students first. Of course, everybody says they’ll put students first (talk about a layup). But the reality is that Washington is swarming with organizations that represent influential institutions, systems, and employees. There can be great pressure to focus on the care and feeding of these groups. For better or worse, and even when it annoys allies or powerful interests, the secretary needs to be the one steadfastly bringing the focus back to the students in our nation’s schools and colleges. This is essential, particularly at a time when Covid has left so many students and families feeling like their needs are being treated as an afterthought.

A broad knowledge of education. The Department of Education’s brief covers pretty much the whole of American education, ranging from special education to college affordability to monitoring educational performance. While Washington plays a much larger financial role in higher education than in K-12 schooling, the secretary’s public role has more often emphasized K-12. A secretary with a broader familiarity with the broad expanse of education has a leg up in setting priorities, asking the right questions, and anticipating challenges.

An understanding of the federal role. Some awareness of the breadth of education can be invaluable. But it’s also vital to appreciate that Washington doesn’t run America’s schools or colleges. In our federal system, short of the occasional major legislation, Washington’s role is frequently a matter of modest executive actions, high-profile commissions, and the bully pulpit. By themselves, these things rarely yield dramatic change—such movement requires broad coalitions and state-level leadership. A secretary benefits immensely from understanding this dynamic and knowing how to navigate it.

A respect for data. The Department of Education houses the Institute of Education Sciences and is charged with supporting research and reporting on the nation’s schools and colleges. That means, especially in the time of Covid, that the secretary should be a champion of transparency and rigorous evidence. This can be tougher than it sounds since what some regard as “following the evidence” can strike others as thinly-disguised partisanship. Concerning Covid, for instance, while teachers’ unions have argued that a respect for science requires emphasizing public-health challenges, Republicans have tended to focus on the evidence suggesting that reopening has generally proven safe.

An ability to transcend divides. President-elect Biden has spoken powerfully and laudably in recent days of his desire to be a unifying leader, promising to work “as hard for those who didn’t vote for me as those who did” and calling for “this grim era of demonization . . . to end here and now.” And, generally speaking, a secretary of education also benefits from a willingness to speak inclusively and work across the aisle. This is particularly true given that the disagreements on many educational questions—charter schooling, accountability, or college affordability, for instance—don’t always map neatly onto familiar political divides.

A thick skin. It’s safe to predict that the next secretary of education won’t face the same unrelenting hostility that greeted Betsy DeVos in 2016. (Recall that DeVos was harshly criticized for all manner of offenses, real and imagined, from the day her nomination was announced.) But it’s also a surety that the next secretary will encounter tough-minded criticism. The ability to shake it off, resist the temptation to lash out at critics, and keep moving forward is part of the job.

I can’t claim much insight into who will fill the secretary of education’s office come early 2021, but I am confident that a nominee who embodies these traits will be best equipped for the demands of the role.

Frederick Hess is director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute and an executive editor of Education Next.

This post originally appeared on Rick Hess Straight Up.