4 ways schools use video game design to spark interest in computer science

Districts can hook students with existing enthusiasm, helping them build technical and soft skills while also broadening STEM diversity.

K-12 DIVE | by Lauren Barack | December 9, 2020

In the Lewisville Independent School District in Texas, video game design and programming courses typically get 200 students a year to sign up — but only about 150 can enroll. That interest, and the subsequent waiting list, is a sign of how eager students are for these courses that Technology Exploration and Career Center East Director Adrian Moreno, along with teachers Billy Carter and Kevin O’Gorman, shepherd in the district.

While most of these students may never have designed or coded a video game before, nearly all have held a controller or navigated a game, as 90% of children ages 13 to 17 play video games on a computer, game console or cellphone, according to the Pew Research Center.

That fact isn’t lost on the teachers at Lewisville ISD.

“In the 1960s, everyone wanted to be a filmmaker. In the 1970s, they wanted to study broadcasting, and video gaming is the current hot one,” O’Gorman told Education Dive. “Today, all the kids have grown up with the internet, wireless devices and streaming video. Here, they get their finger on how to create that world and want to make [games] or mess around with them.”

For districts looking to build more science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) connections into curriculum, game design and programming can serve as an immediate gateway by tapping into students’ interests, strengthening their connections to what they’re learning, and even build additional skills to help them in school as well as their professional life.

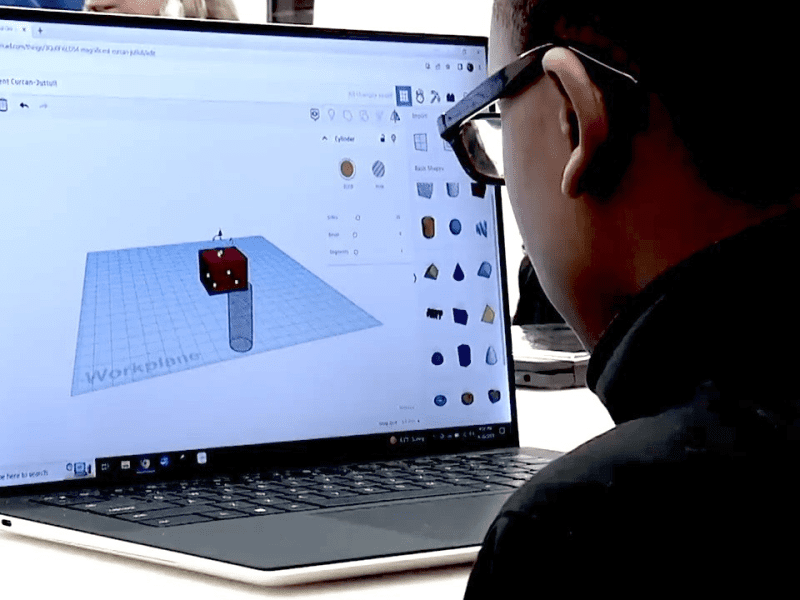

Students build foundational technical skills

In Lewisville ISD, students who get a spot in one of the classes work on top-of-the-line Macs and Alienware PCs — computers that professional game developers use. Classes also mirror, in some ways, how professional game companies work, too. For example, the students are expected to place some of their finished games into the hands of reviewers to get feedback on what works, and what doesn’t.

In Lewisville, reviewers come in a pint-sized form — the district’s kindergarteners.

Students are tasked every year with designing an edutainment game, delivering a lesson in an entertaining way. They can choose the subject and the lesson they want to deliver, but when the kindergarteners get their hands on the games, they’re not just playing for fun, they’re giving feedback, said Carter. That way they can tell the high school students whether the games are too hard or too easy — and if they’ve actually learned something.

“After the kindergarteners leave, we sit and discuss their feedback,” said Carter. “As for the kindergarteners, the principals says the students look forward to it every year.”

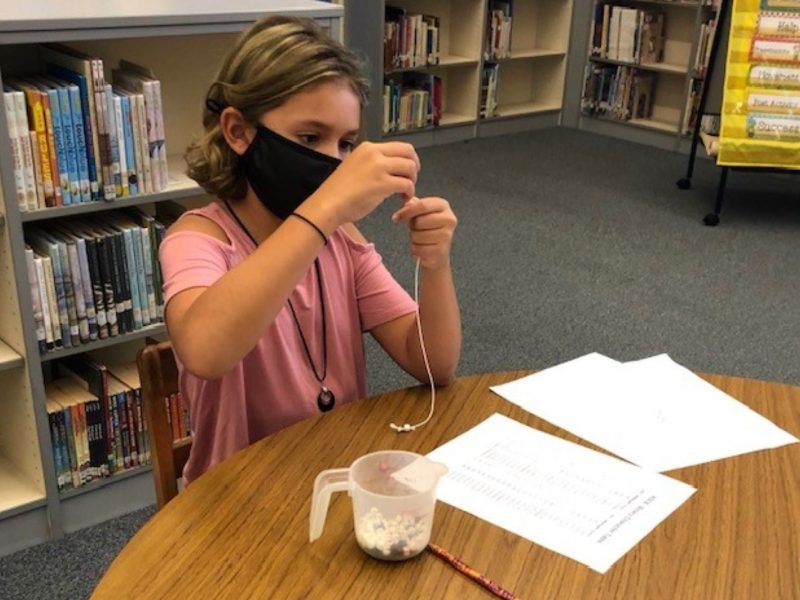

Seeding STEM skills into elementary grades

While Lewisville ISD hands the role of video game reviewers over to its kindergarteners, the classes are for high school students. But video game design and programming can be taught to very young students, as well — a push staffers at New York Hall of Science are making, looking at how to engage elementary school students in building, creating and writing video games.

The science museum, based in Queens, New York, holds summer classes, trains teachers and runs student workshops at schools. Typically, they’ve worked with middle and high school students, but are now “trying to engage younger audiences in these concepts,” said Anthony Negron, NYSCI’s manager of digital programming. The organization shifted to online during the pandemic, doing fewer programs.

Classes for younger students start with Scratch, a simple drag-and-drop programming language developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab. The first project with Scratch is to typically build a maze challenge, said Negron, which not only helps them learn the programming language, but gives them a project or goal rather than a set of rote lessons to complete. That proves to be more engaging, with a wide variety of projects produced in the end.

“We’ve seen kids use Scratch to build out the narrative of a story they’re reading,” he said. “And we’ve seen them use Scratch to build out games to address a community issue.”

Soft skills aren’t omitted

While the teachers in Lewisville are aware not every student will go on to be a video game designer or programmer, they believe the skills they learn can help them succeed in any work environment. These include soft skills like knowing how to write a strong resume or build a presentation, abilities employers state they want to see in young job candidates.

“We have business partners, and we’ve asked them if we are teaching students the right curriculum,” said Carter. “And one of the things they talked about was how important these soft skills were.”

Sharon Lambert, a teacher at Florida’s Dunnellon High School, also helps her game design and programming students develop soft skills. After piloting the courses several years back with free resources from the web, Lambert has seen Marion County Public Schools expand the program to where students can now take multiple courses and learn programming languages including Python, Unity and C-Sharp, in addition to other digital tools including Blender.

“I’m making sure that kids know there’s a lot more to game design than just playing a game,” she said. “And they may not realize that.”

While she wants students to master these professional tools, she also wants them to leave with soft skills so they’re not just fluent in how to code a game, but how to navigate a professional work environment.

“Games and programs are not built by one individual usually,” she said. “It takes a team, and learning how to work on a team is an important skill that students learn. From … communication, time management, integrity, organizational skills and others, soft skills are important to them so they can be able to compete and function successfully in the job market.”

Gateways to broadening computer science diversity

Video games not only tap into students’ interests, they can also help bridge excitement for computer science classes. Yet while most teens have played a video game, most high schools in the nation don’t have computer science in their curricula, said Jake Baskin, executive director of the Computer Science Teachers Association in Chicago, Illinois.

But for those schools looking to use video game design and programming as a gateway to new CS courses, Baskin said they should be clear about what the courses will entail — both to students who want to sign up, and to the educators about what they want to convey.

“It’s important that video game development does not mean free range to play video games as much as you want,” he said. “When video game development is taught in a way that includes vigorous [computer science] education, that’s a wonderful way to ensure students engage in high-quality content.”

Baskin also believes game design and programming courses can give schools and districts an opportunity to think intentionally about equity and inclusion, ensuring they’re welcoming all students, as women and students of colors are historically “dramatically underrepresented in CS courses,” he said.

And where districts have been “thoughtful from the start,” Baskin said, there’s been increased engagement in CS courses and also increases in young women taking AP exams in computer science, as well.

“I think there are opportunities to integrate [computer science] in almost any curricula,” he said. “And for principals who say they don’t have funding, I would ask them to think creatively where they have resources, and where they can be integrated.”