Jeff Bezos is riding his own rocket. He dreamed of space as a Miami high school student

Miami Herald | By Jeff Kleinman | July 19, 2021

Jeff Bezos is flying to the edge of space in his own capsule this week. But his interest in exploring new worlds didn’t come suddenly.

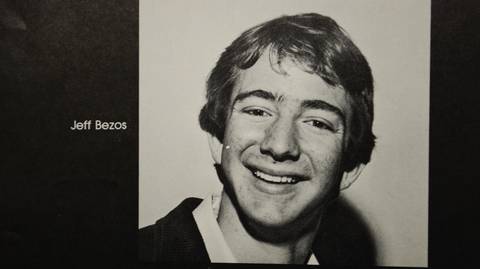

His fascination with space stretches back to his childhood and into his teen years as a student at Miami Palmetto Senior High, where he was the valedictorian in 1982.

What was on the mind of the young Bezos, Amazon founder and Washington Post owner, leading up to his latest adventures as a middle-age billionaire?

Let’s look into the archives of the Miami Herald to find out.

PLANS TO CHANGE THE WORLD

Published Aug. 6, 2013

By Luisa Yanez

When Jeffrey Preston Bezos graduated from Miami Palmetto Senior High in 1982, he had big plans to change the world.

The valedictorian, National Merit Scholar and Silver Knight award winner for science told the Miami Herald he wanted to “build space hotels, amusement parks, yachts and colonies for two or three million people orbiting around the Earth.”

Eventually, his grand plan included getting everybody off the blue planet and turning it into a big park of sorts.

“Even when he was in high school, all the teachers who taught him knew Jeff was something special and that he would be going places,” said Palmetto science teacher Cullen Bullock, a 33-year veteran at the school.

Bezos certainly did change the world, founding Amazon.com, the largest retailer on the World Wide Web, and creating a model for Internet sales.

And on Monday, he made jaws drop again with reports that he had purchased The Washington Post for $250 million. Bezos, one of the world’s wealthiest men with a net worth of more than $22 billion, said he intends to apply his savvy as an e-merchant to one of the premier newspapers in the world, which has been struggling financially.

Even back in his high school days, Bezos talked about amassing a fortune, recalls former girlfriend Ursula Werner.

“Jeff always wanted to make a lot of money,” she said. “It wasn’t about money itself. It was about what he was going to do with the money, about changing the future.”

The couple were featured in a Miami Herald Neighbors story just weeks after their graduation from Palmetto in June 1982. They talked about a special project they had launched – an early sign of Bezos’ imaginative mind.

Bezos and Werner conducted a 10-day course for 10-year-old students to teach them about Jonathan Swift’s book Gulliver’s Travels, about black holes in space, nuclear war and how electric currents work. The Ivy League-bound students – Bezos was headed for Princeton – called it “The Dream Institute.”

At Palmetto High, teachers and fellow students knew Bezos as one of the smartest students in a school full of smart kids with an obsession about space colonies.

Rudolf Werner, Ursula’s father, remembers Bezos’ big talk about space life.

“He said the future of mankind is not on this planet, because we might be struck by something, and we better have a spaceship out there,” Werner told Wired magazine.

To this day, Bezos retains his interest, as well as a business interest, in the space industry. In 2000, he founded a space flight company called Blue Origin and has been active in recovering rockets used during moon exploration missions.

Joshua Weinstein, Bezos’ best friend at Palmetto, told the magazine there was nothing “spacey” about his friend.

“Jeff was always a formidable presence,” Weinstein said.

When Bezos made clear his intention to become class valedictorian, Weinstein said everyone knew they were now working for second place. Bezos graduated first in a class of 689.

Born in Albuquerque, N.M., Bezos had ended up in Miami-Dade thanks to his adoptive father, a Cuban exile.

Mike Bezos, who came to the United States alone as a teenager in 1962 as part of the famed Operation Pedro Pan, had settled in Albuquerque to attend college, and met and married Bezos’ mother, Jackie. Mike Bezos eventually adopted the 4-year-old Jeff, giving him his last name.

“I’ve never met him,” Jeff Bezos said of his biological father in a 2011 interview with Wired. “But the reality, as far as I’m concerned, is that my Dad is my natural father. The only time I ever think about it, genuinely, is when a doctor asks me to fill out a form.”

Mike Bezos joined Exxon as a petroleum engineer and the family moved several times during Jeff’s childhood, from Albuquerque to Houston, then briefly to Pensacola, and then to Miami.

Today, Jeff Bezos’ name is on a plaque outside Palmetto’s school auditorium, honoring notable graduates.

“Most of the students know Amazon’s founder graduated from the school and are very proud of it,” Bullock said.\

DREAMING

Published July 4, 1982

By Sandra Dibble

Give them just two weeks, the two Palmetto High graduates say — just two weeks — and they could “open new pathways of thought” for some fifth-grade pupils.

Ursula Werner and Jeff Bezos, Palmetto classes of 1981 and 1982 respectively, are conducting a 10-day course this summer for 10-year-old students, teaching them about Jonathan Swift’s book (ITALICS:)Gulliver’s Travels, about black holes in outer space, about electric currents and nuclear arms limitations talks, about how to operate a camera.

They call it The Dream Institute.

“We don’t just teach them something,” said Bezos. “We ask them to apply it.”

Between 9 and 12 every weekday morning since June 21, Bezos’ comfortable, carpeted bedroom becomes a classroom for Christina, Mark, Howard, Merrell and James.

If the course and setting are unusual, so are the teachers. Werner and Bezos were valedictorians at Palmetto. Both have won Silver Knight awards, Werner for English, Bezos for science. Next year, Bezos heads for Princeton University to study engineering. Werner, who plans to major in English, has just finished her first year at Duke University.

Werner and Bezos spend their mornings teaching, their afternoons planning for the next day’s class, researching and discussing ideas.

“I learn as much as the kids do,” Werner said.

Wednesday’s class, about communications, included: readings from Gulliver’s Travels and Richard Adams’ Watership Down, three newspaper articles (about bass dying from pollution, about Reagan’s foreign policy and about nuclear proliferation), and a short talk about the Bezos family’s Apple II computer.

James Schockett enters fifth grade next year at Pinecrest Elementary. He is an eager student.

At The Dream Institute, James said, he has learned “little neat things that I really think are neat. We study about black holes in outer space. We study about stars … We learned that one teaspoon of a neutron star would weigh 10 billion tons.”

In class, after a discussion of Gulliver’s Travels, James clamored to make an important point: Since the Lilliputians are so tiny and Gulliver is so large, wouldn’t it take several generations of Lilliputians to decapitate Gulliver?

The Dream Institute is better than school, said James, who likes to swim and thinks he may become a doctor. “In school, you’re getting a grade. Whenever you’re getting a grade for something, you always feel slightly pressured.”

Merrell Maschino, James’ classmate at Pinecrest, lists another advantage: “You can call him Jeff instead of Mr. Bezos. It’s like having a big brother teach you.”

Bezos and Werner charge $150 for the two-week session, taught out of Bezos’ parents’ house at 13720 SW 73rd Ave. They gear the course to fifth-grade students, Werner said, “because we decided that age is pretty creative, but also intelligent enough to understand how things work.”

Teachers often underestimate their students’ abilities, Bezos and Werner say, and they are careful not to do the same.

Said Werner: “You have to shock them into thinking they can do more than they think they can.”

LOOKING TO THE MOON

Published Aug. 1, 1999

By John Dorschner

Jeff Bezos has always dreamed in cosmic terms. Think Earth. Think space.

When he attended Miami Palmetto High, he wanted to be an astronaut. He envisioned building orbiting hotels, amusement parks and colonies for millions of residents so that the Earth could be preserved with vast parks.

These days, as the leader of Amazon.com, his ambitions are still global, and he boasts that he has become the shopping mall for the planet. “We’re the Earth’s biggest selection,” he proclaims.

His grand visions have led to astonishing results. Only four years ago, he sold his first online book. Today, he has 10.7 million customers. At age 35, his Amazon stock is worth nearly $6 billion.

Yet he says he really isn’t that interested in making money. He claims he doesn’t closely watch the stock price and he disdains moving his money-losing company toward quick profitability.

“First and foremost, we want to be the Earth’s most customer-centric company,” he said in a telephone interview. He’s trying to build a business that will be a global friend to consumers for decades to come.

That philosophy translates into soaring revenues – and soaring losses. Each quarter, he gets further away from turning a profit. He says it’s more important to look at the bigger, historical perspective. “We want to have stories to tell our grandchildren.”

Such talk has turned off some financial analysts, and the stock, which flew as high as $221 in April, has fallen to its current $100. In a June cover story, Barron’s called Bezos’ firm “Amazon.bomb.”

Bezos shrugs off such criticism, and a friend says getting rich never was high on his priorities. “He’s not a material guy,” says Joshua Weinstein, a buddy at Palmetto High who is now a reporter for a newspaper in Maine.

In fact, as late as last year, when Bezos’ stock was worth $4 billion, he and his wife were still living in a small one-bedroom apartment in Seattle. He just didn’t want to take the time to find something grander. *

Jeffrey Bezos’s mother is Jackie Gise, daughter of an executive with the Atomic Energy Commission. Bezos has never known his biological father. Miguel Bezos adopted him soon after he married Jackie.

At the time, Jackie was a teenage bank clerk. Miguel was a young engineering student at the University of Albuquerque.

Born in Cuba, Miguel was a Pedro Pan child, coming to the States by himself when he was 15. He was sent to Delaware where he lived in a Catholic mission with other children whose parents had wanted them to escape commu-nism.

After college, Miguel – Mike to his American friends – became a petroleum engineer for Exxon – beginning a career that caused the family to move frequently.

“My mom is an expert at packing,” Jeff said. They moved so often, it became routine. “It was never a trauma or anything.”

Each time Mike was transferred, the family tried to choose a new neighborhood with the best schools for Jeff and his two younger siblings. In Houston, he attended a magnet elementary school that was one of the first to teach younger children how to program computers.

After a brief stint in Pensacola, the family moved to South Florida just before Jeff started 9th grade. They chose a house in South Dade near Palmetto High, which long has had among the highest test scores of any public high school in the county.

“Palmetto was a terrific school,” he said. “I had a bunch of great teachers.”

Bill McCreary, a science teacher: “He was an awesome kid, one of the best we ever had. He worked hard and he didn’t have to, he was so bright.”

Weinstein, who lived around the corner from Bezos, said Palmetto’s class of ‘82 was extremely talented, but no match for Bezos: “He was, and is, a very driven guy. When he decided he wanted to be valedictorian, everyone else decided to try to be No. 2.”

One subject that he was not enthused about was Spanish. “I took Spanish all my high school years, and it hasn’t stuck with me very well,” Bezos said.

Spanish wasn’t regularly spoken in the Bezos home, and Weinstein said, “When his abuela [grandmother] visited, I’d translate for Jeff.”

He was something of a nerd, and he drove a dumpy Falcon station wagon into a school parking lot filled with fancy Camaros, but he had an infectious laugh and was far from anti-social. “After the prom,” Weinstein said, “the party was at his house.”

One summer, he worked at a McDonald’s on U.S. 1. “Every Saturday morning, I would scramble several hundred eggs.” He thought that was “a complete blast,” but the next summer, he and a girlfriend, Ursula Werner, created the Dream Institute, an educational summer camp for a half-dozen kids, whose parents paid $600 each to have two brainy students talk about English and science.

He realizes he would never be a physicist.

Bezos ended up as valedictorian and went off to Princeton, dreaming of becoming a great theoretical physicist. But he discovered that the university, where Einstein had once taught, was filled with brilliant physics students.

He realized “I would be a mediocre physicist at best,” and by his junior year he found himself “pulled inexorably toward the computer stuff.”

Graduating with a degree in electrical engineering and computer science, he went to work for a tech firm. Several years later, he moved to a tech-oriented hedge fund, D.E. Shaw. In four years, he rose to senior vice president in charge of exploring new business opportunities.

In 1994, he came up with an idea: Selling books on the Internet. He sensed the Internet was the wave of the future, and though some observers thought TV was killing reading habits, Bezos believed books remained “the most efficient way of moving a large amount of information from one person to another.”

His boss wasn’t enthused.

Bezos was already “making an enormous amount of money,” said his buddy Weinstein, and if he stayed a few more months at Shaw, he would have received a bonus “that would have been as much as a normal person would make in two or three years.”

But Bezos, always the cosmic thinker, wondered what he might think, 60 years hence, sitting in a rocking chair: Would he have been happy thinking that he had stayed in New York for a good chunk of cash – or that he had been in at the start of a sea change that would be as major an event as the dawn of the industrial revolution?

History won out. He quit his job and with his wife, MacKenzie, a writer, flew to his parents’ home in Fort Worth. His folks became his first investors. He didn’t try to oversell them. “I told them they would lose their entire investment – because I still wanted to be able to go home for Thanksgiving.”

And come home he can. Mom and dad’s Amazon stock is currently worth about $900 million. Still, Mike Bezos labors for Exxon. “He’s worked for over 30 years,” said Jeff. “I don’t think he would know what to do with himself if he didn’t work.”

On the way, Bezos taps out a business plan

Borrowing a car from his parents, MacKenzie and Jeff headed west. She drove while he tapped out a business plan on a laptop. They stopped in Silicon Valley to hire several programming types, then headed to Seattle, which he chose because it was close to a major book warehouse and a large work force of computer nerds. His hedge fund connections helped obtain more venture capital.

When they opened for business in the summer of 1995, he offered deep discounts to attract buyers. “Customers are very rational. They want great prices and great service, and at Amazon.com, we have focused on these.”

Initially, many computer users were nervous about giving their credit card numbers over the Internet to an unknown entity, but the news quickly spread, primarily through word of mouth: You could get a book at a discount – and it came quickly.

While traditional booksellers began waking up to the potential of the Internet, Bezos aggressively kept branching out, opening Amazon sites in the United Kingdom and Germany. Amazon now offers music, videos, toys and electronics. It has purchased large stakes in Drugstore.com, Pets.com, HomeGrocer.com (offering home delivery of groceries in Seattle and Portland) and Gear.com, selling sporting goods.

It challenged another Internet giant, eBay, by offering online auctions and then, to go beyond Beanie Babies and yard-sale items, it bought a $45 million stake in Sotheby’s, the venerable London auction house, with plans to do online auctions of high-quality collectibles.

Amazon has a billion-dollar reserve for more acquisitions. It is no longer an electronic Barnes & Noble. It’s becoming a shopping mall. Even at its present reduced levels, Amazon’s market cap – total shares multiplied by stock price – is still $16 billion, almost a billion more than the market cap of the century-old Sears, though the established retailer has more than $35 billion in annual revenues and pays a dividend of 92 cents a share, while Bezos’ firm has $1.4 billion in revenues and has yet to earn a penny.

Though Bezos has an easy-going personality, he has a reputation as a tough competitor who wants to grab as much Internet territory as he can. In May, when Barnesandnoble.com was about to put out an initial public offering, Bezos announced Amazon would start selling best-sellers at 50 percent off list price – a stunning discount, one on which virtually no retailer could make money.

Fortune Magazine noted that a new expression had entered the business lexicon – “getting Amazoned,” meaning getting knocked out by an Internet competitor.

In fact, many competitors – from small bookstores to toy shops – have complained that Amazon could kill off a huge number of businesses, and then might collapse itself without earning a profit.

When asked about the P-word, Bezos sighed, “People ask me this question all the time.” Eventually, he admitted, a company must earn a profit, but he said thinking of profit is “like worrying about gravity. . . . It’s part of the landscape.” But, he added, “it would be a mistake to go for short-term profitability.” Analysts wonder when the profits will come

Right now, he is interested in “building a great customer experience.” He wants visitors to trust his site, to be entertained, to be informed. “We’ve got 10 million customers, but there are still lots of people who haven’t even shopped once on the Internet.”

Two weeks ago, Amazon announced second-quarter results that dismayed some analysts. Sales zoomed to $314 million – up 171 percent from the $116 million in the second quarter of 1998 – but the pro forma net loss for the quarter climbed to $82.8 million, or 51 cents per share, compared to a loss of $17 million – 12 cents share – in the second quarter of 1998.

Barron’s said last week the earnings results reinforced the magazine’s June report that Amazon is in danger of bombing. That cover story stated that, rather than being a modern high-tech company, Amazon was really an old-fashioned middleman, “and [Bezos] will likely be outflanked by companies that sell their wares directly to consumers.”

New technologies will allow consumers to download their books directly from the Internet, Barron’s said, and as Bezos expands, he is building more warehouses and piling up inventory, getting into the “bricks-and-mortar” albatross that his more traditional competitors have been saddled with.

Other skeptics wonder if the Internet retailer will ever be able to achieve decent profit margins. While a customer in his car might visit three stores before buying a TV, a Web surfer might have a hundred sites a mouse-click away, as well as sites that tell customers where the best price can be found.

Indeed, one of Amazon’s top electronic-store sellers last week was the Toshiba SD-3109 DVD player at $399.99, a discount of $100 from standard retail, but if a Web surfer went to Dealtime.com, he found at least nine online stores offering better deals. Lowest price: $319.95.

Still, none of those competitors had anywhere near the name-recognition of Amazon, and there’s been a proven reluctance by the public to send money to an Internet company that customers know nothing about. Amazon proudly points out that people trust it: About 70 percent of its business now comes from repeat customers.

David Cooperstein, an analyst with Forrester Research, thinks Bezos is correct in concentrating on pleasing customers. “Their future is strong. You get their package with the great bubble wrap, and you know someone’s taken care with that product.”

What’s more, said Cooperstein, the interactive Internet allows Amazon to record data about what customers like, so they can cater directly to their interests and send them e-mails about future sales. “That database is their strategic asset.”

Since starting Amazon, Bezos hasn’t had a lot of free time. He works about 60 hours a week, including weekends. As the business has grown, he has sought the help of more seasoned retail managers, including several from Wal-Mart, and a few weeks ago, he hired a Black & Decker executive as president “to expand the executive bandwidth of our team.”

Last fall, he finally cashed in some of his stock, selling 180,000 shares for $22.8 million. He used some of the proceeds to buy a large house in an affluent neighborhood of Microsoft alums.

He still finds time, however, to dream of space. Though he envisions Amazon only as the shopping mall of the planet, he confesses that he sometimes can’t help but look to the moon. “I wish they made deliveries!”