As Private School Choice Grows, Critics Push for More Guardrails

Education Week | By Mark Lieberman | January 16, 2024

Critics of programs that allow parents to spend state funds on private school options for their kids want more regulatory scrutiny over where the funds go, what parents do with them, and how participating students fare in the classroom.

In Arkansas, a coalition of education advocacy organizations including the state teachers’ union is pushing to secure a referendum spot on the election ballot this November asking voters to support requirements for all schools that receive state funds to comply with the same standards for academics and accreditation.

Arizona’s governor recently unveiled a proposed legislative package that would require students to attend public school for 100 days before becoming eligible for a state-funded voucher to pay for private school tuition.

And advocates for transparency and accountability are trying to persuade lawmakers in states like Tennessee to prioritize those values as they begin to craft potential new private school choice programs.

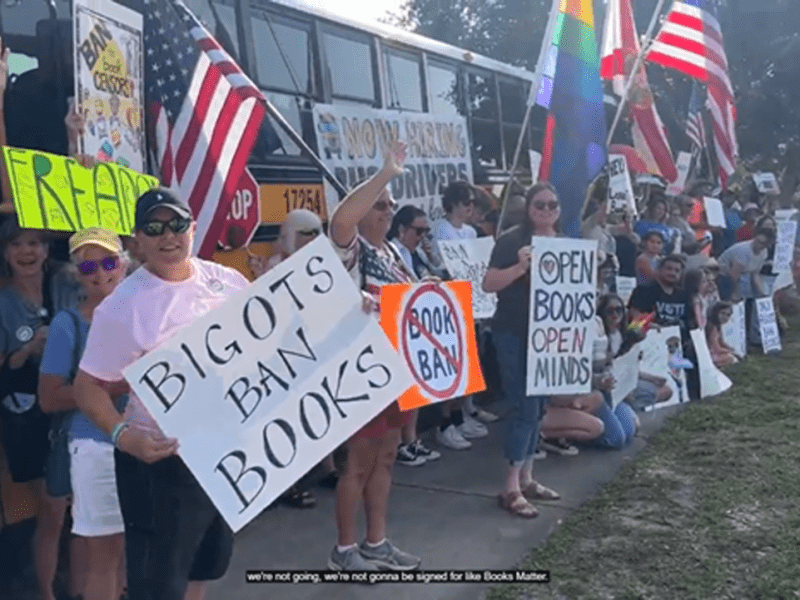

Many public school districts and public education advocates steadfastly oppose vouchers, education savings accounts, and tax-credit scholarships—programs that allow parents to use state funds on private school tuition and other private education expenses, including for homeschooling.

But their concerns haven’t stopped conservative-led states from charging ahead. Nine states allow, or are poised in the coming years to allow, the vast majority of K-12 students to apply for public funds to pay for private school and homeschool expenses. Several of those states, including Ohio and Florida, passed their expanded programs within the last year.

Supporters of private school choice argue that parents will ensure that their child’s education is meeting their needs.

“Parents are the best form of accountability. They have their child’s best interest in mind and will hold schools accountable to that end,” a spokesperson for Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee told the Chattanooga Times Free Press last month. Lee wants to expand the state’s education savings account program, which is currently limited to a handful of counties, to make all students across the state eligible.

But some experts believe parents may not have the tools to serve as the primary accountability backstop for programs that cost hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars.

“There’s a lot of emerging data about the mismatch between how parents think their kids are doing and how they’re actually doing,” said Liz Cohen, policy director for FutureEd, an independent think tank based at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. “To have an independent data point certainly seems like it would be helpful.”

Advocates want more data on how private school choice funds are being spent

The situation in Arkansas illustrates the evolving tactics private school choice opponents are deploying.

Last August, public school advocates in the state failed to secure enough signatures for a ballot referendum that would have asked voters whether or not to repeal the state’s newly passed education savings account program. The LEARNS Act, signed into law in March 2023, will in the coming years make every Arkansas student eligible for a state-provided sum—currently, up to $6,600 this year—to cover private school or homeschooling expenses.

Instead, the policy’s opponents are now aiming to ramp up guardrails around the new program. If voters approve the referendum, schools that receive voucher funds would be forced to adhere to standards for academics and accreditation that match those that apply to public schools. Schools that fail to comply would be ineligible to accept voucher funds.

To get that issue before voters, the groups still have obstacles to overcome. A new state law, currently facing a legal challenge, requires signatures from a larger number of counties than before in order for a measure to qualify for the ballot. The state’s attorney general last week also asked the groups to revise the ballot referendum language for clarity.

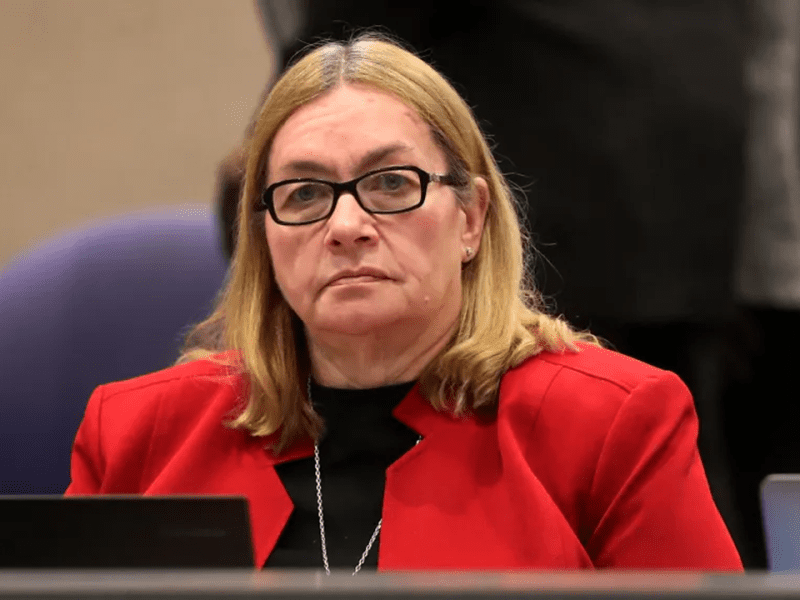

In Arizona, obstacles to accountability come down to a partisan divide. Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs has harshly criticized the state’s universal education savings account offering championed by her Republican predecessor and supported by the Republican majorities in both legislative chambers.

Critics of the program have raised allegations that parents have spent ESA funds on items that don’t serve an educational purpose. But Hobbs has in recent weeks centered her ESA criticisms on cost overruns in the program as the state’s budget deficit is projected to grow to $879 million next year. The cost of ESAs has ballooned beyond projections—more than 73,000 students, or 6 percent of the state’s K-12 population, have already signed up, and thousands more are likely to do so in the coming months.

Hobbs is aiming to trim $244 million in ESA program expenses by requiring students to have attended 100 days of public school before securing state funds for private school choice. A year ago, the state’s department of education reported that more than half of students enrolled in the ESA program hadn’t previously attended public schools, consistent with similar programs across the country. Many of those parents would no longer be eligible for ESA funds from the state if Hobbs’ proposal goes through.

Republican lawmakers in Arizona have already signaled they have no intention to support her proposed policies.

Some of the increased momentum around accountability for private school choice funds vouchers stems from the expansion of options on how families can spend the money through the proliferation of education savings accounts, said Chris Lubienski, a professor of education policy at Indiana University. Vouchers must be spent on private school tuition. Parents can spend ESA funds on anything from tuition and fees to technology and classroom materials, often broadly defined.

“There was kind of a market-based accountability [with vouchers]—parents are going to choose within a marketplace where, if a school is inefficient, if it’s wasting money, consumers will discipline them,” Lubienski said. “Now when we’re giving the money directly to parents to spend on all different types of things, we lose that school- or organization-level accountability. Parents are free to do what they want.”

What should accountability look like?

A proposed new ESA program in Wyoming has drawn competing views from state lawmakers on the level of state regulation necessary. Some want to require vendors that receive state funds to be certified by the state. Others believe a higher priority is preventing the state from intervening in private school curricula, according to reporting from Cowboy State Daily.

Wyoming lawmakers can look to many states that already have accountability measures in place for voucher and ESA programs, as shown in a legislative tracker maintained by FutureEd. But no two sets of state policies look identical.

Some, like Alabama and Indiana, require students who receive funds for those programs to take the same state-mandated exams given to all public school students, or to take exams with comparable levels of rigor. EdChoice, a leading nonprofit organization advocating for private school choice programs, calls requirements for all students to take the exact same test “unnecessary and counterproductive.”

Some require publicly available quarterly reports outlining key statistics on how many students are participating and where they’re coming from.

Some require parents to pay expenses first and then get reimbursed after a review of their receipts. Others give parents pre-loaded debit cards that only permit certain approved transactions to proceed.

Some administer ESA and voucher programs on their own, while others invest in contracts with one of a handful of outside vendors.

And nearly all private school programs include a provision, crafted by conservative proponent groups like the American Legislative Exchange Council, that shields private schools receiving state funds from facing state-mandated changes to their “creed, practices, admission policy, hiring policy or curriculum.” Voucher critics argue such policies increase the likelihood that private schools will discriminate against LGBTQ+ students or students with disabilities.

Researchers who examine private school choice say there’s no one-size-fits-all resolution to these disparities. But they are eager in general for more granular data.

Cohen said she’d like to see a deeper look at whether and how vouchers and ESAs increase student “mobility” from one school to another, which can be harmful to academic progress.

Accountability measures represent only one step in the ongoing debate over the effectiveness of the private school choice model. In Tennessee, where students receiving ESA funds must take state exams, Democratic lawmakers recently grilled the state education chief over the takeaway from emerging academic data showing ESA students performing poorly compared with their public school peers.

“The results aren’t anything to write home about,” Lizette Reynolds, the state’s education commissioner, said during a committee hearing. “But at the end of the day, parents are happy with this new learning environment for their students.”