Body-slam incident at Liberty High renews debate about roles, training of on-campus cops

Orlando Sentinel | by Cristóbal Reyes | February 22, 2021

A week and a half after Osceola school resource Deputy Ethan Fournier was videoed knocking a 16-year-old student unconscious by slamming her into pavement at Liberty High School, members of the public flocked to a forum hosted by community leaders.

At Solid Rock Community Church in Kissimmee on Feb. 5, a panel of former school principals, an Osceola school board member and a retired Osceola County Sheriff’s Office official faced two common questions: What is the proper role for school resource officers on school campuses? And how are they being trained to perform those duties?

According to expert interviews and contracts between Central Florida school boards and the law enforcement agencies with which they partner, the answers to those questions vary and are often ill-defined. While Florida law mandates some form of armed security be present on campus — with options from police to armed faculty — it mostly leaves the details of that relationship to local school districts.

Changes to the way Osceola County schools are policed could be coming, as an advisory committee led by school board member Julius Meléndez seeks to create new policies to accompany its contracts with the Sheriff’s Office and the Kissimmee and St. Cloud police departments.

“We’re not writing policy in a vacuum,” Meléndez told the Orlando Sentinel in an interview, while declining to talk specifically about the incident at Liberty High. “We have the ability to influence the decision-makers at each respective agency and make sure that it’s implemented and sustained.”

The questions come as activists in Central Florida and elsewhere reignite calls to remove SROs from public schools. They argue that stationing officers on every campus following the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland has led to the criminalization of youth misbehavior, disproportionately affecting Black students and others of color.

While some research has found that to be the case in Florida, it has also identified as a factor the lack of specific guidance for SROs by school boards and differing training practices from county-to-county and agency-to-agency, experts said.

SRO advocates are wary of calls to remove officers from schools, saying high-profile violent incidents like the one at Liberty High aren’t representative of their job. They say SROs develop relationships with students and many are beloved on the campuses they serve.

“One thing we don’t do very well in the policing world is that we don’t take enough credit for all the things we do,” said Timothy Enos, executive director of the Florida Association of School Resource Officers (FASRO) and chief of the Sarasota County Schools Police Department. “There are a lot of great stories out there, but SROs don’t do it to say, ‘Look at me!’ They do it because they want to go the extra mile for the kids.”

How are SROs trained?

Currently, there are no state-mandated requirements to becoming an SRO in Florida, aside from the evaluations and training required to become a sworn officer.

But because they’re part of a specialized policing unit, it usually takes a few years before officers are assigned to work on public school campuses. By then, they are taught in areas related to school policing through FASRO and FDLE — which offer courses on subjects like language barriers and students with special needs — and trained by their agency or the local academy.

Some larger agencies, like the Seminole County Sheriff’s Office, offer specialized training before SROs step foot on campus. That includes required education in student threat assessments, mental health awareness and de-escalation tactics, according to the agency’s contract with Seminole County Schools.

But because smaller agencies around Florida may not have the resources and manpower to provide the in-depth training, FASRO recommends all SROs take classes through the state, which helps to standardize expectations on campuses, Enos said.

“There are things that are specific that would make an officer better at dealing with children based upon those courses, but right now there’s no minimum requirement to be able to be on a campus,” Enos said.

In Osceola and elsewhere, training happens year-round, with constant refreshers for SROs scheduled on days when classes are not in session, said a longtime instructor at the Criminal Justice Academy of Osceola, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they are not authorized to discuss training practices.

But much of the hands-on training, including for use-of-force scenarios, involves role-playing in ideal conditions, the instructor said. An incident on the job can be more volatile and, because there isn’t a separate policy governing force against minors, it often comes down to what the instructor described as “officer/subject factors.”

“When you say, ‘They’re kids,’ there’s really no such thing because of size differences,” the instructor said, alluding to a Jan. 26 incident at Eustis High School where an officer was recorded using a stun gun in the lunchroom after a student struck him repeatedly. “We’re talking about kids, but what if the kid is 160 pounds and coming at you? That’s not the same thing as dealing with a kindergartner.”

Often, the training doesn’t cover racial bias, which leads to Black children being treated as if they are older, said Kristin Henning, a professor at Georgetown Law and director of the university’s Juvenile Justice Clinic & Initiative.

“The bottom line is that we don’t see Black children as children,” Henning said. “Historically, from slavery to the time of the first juvenile courts, Black kids weren’t seen as worthy of rehabilitation. So now it’s just a continuation of that, the dehumanization, the failure of seeing children as children.”

Sheriff Marco López, who wasn’t invited to the forum at Solid Rock Church, told a Spectrum News 13 reporter he is working on establishing new training guidelines for SROs in response to the Liberty High incident. Nirva Rodríguez, the agency’s spokeswoman, told the Sentinel in an email the document would be released when it’s completed.

Mixed policies, mixed outcomes

A May 2020 report by the U.S. Department of Education found that, while 51% of public schools nationwide had an officer on campus at least once a week in the 2017-2018 school year, only about two-thirds of those schools had formal policies outlining their roles and responsibilities.

Central Florida school boards are among those who have contracts with partner agencies stipulating that officers are not school disciplinarians nor are they tasked with menial duties like hall monitoring or lunchroom security.

However, principals often have wide discretion to request law enforcement involvement with campus incidents, which is what Meléndez is looking to rein in.

One possibility: introducing a “list of non-negotiables” that don’t require SRO intervention as a way to more specifically outline when principals can and can’t call on law enforcement.

“I want our staff to be able to handle some of these incidents, but it’s a balancing act because I also want our staff to feel safe,” Meléndez said. “We can’t just say no police at all.”

Meléndez hopes that clearer policies could prevent violent interactions between SROs and students in the future. The next advisory committee meeting, which is expected to feature St. Cloud police Chief Pete Gauntlett, will be held Wednesday at 5:30 p.m. at the school board building.

An ACLU report released in September found that having officers in Florida schools didn’t reduce the frequency of on-campus incidents, but increased the number of incidents being referred to law enforcement.

F. Chris Curran, the University of Florida professor who wrote the report, said his research has also found positives to having cops on campus. A study released this month that he co-authored found students who often interact with SROs reported feeling more trusting of the officer and safer at school.

But those findings are not universal: Students are more likely to feel safe at schools with formal policies outlining the roles of SROs. And the racial makeup of a school also factors into students’ perceptions.

“It’s important when we put police in schools to acknowledge that and think explicitly about how we’re shaping policies and practices in ways that minimize that unintended consequence while trying to get some of the potential benefits,” Curran said.

While some activists are calling for the removal of SROs altogether, others think there is potential for collaboration between law enforcement and mental health professionals to resolve disputes.

An important step that police agencies can take is training officers to more critically recognize implicit bias in adolescents, said Henning, who is currently working on a training module for the DC Metropolitan Police Department to address engaging Black youth and others of color. The recent incidents at Eustis High and Liberty High both involved Black students and white officers.

One aspect of that training, which is in its planning stages, is avoiding stereotyping Black teens when they act nervous around police, a behavior Henning said is often seen as confirmation of guilt.

“It’s a ridiculous conundrum for those kids, and there are all kinds of training manuals that fail to train police officers on those false positives,” Henning said. “They fail to educate police officers that sometimes kids are anxious and nervous because they’re kids, and sometimes kids are anxious and nervous because they’re Black and afraid of being targeted.”

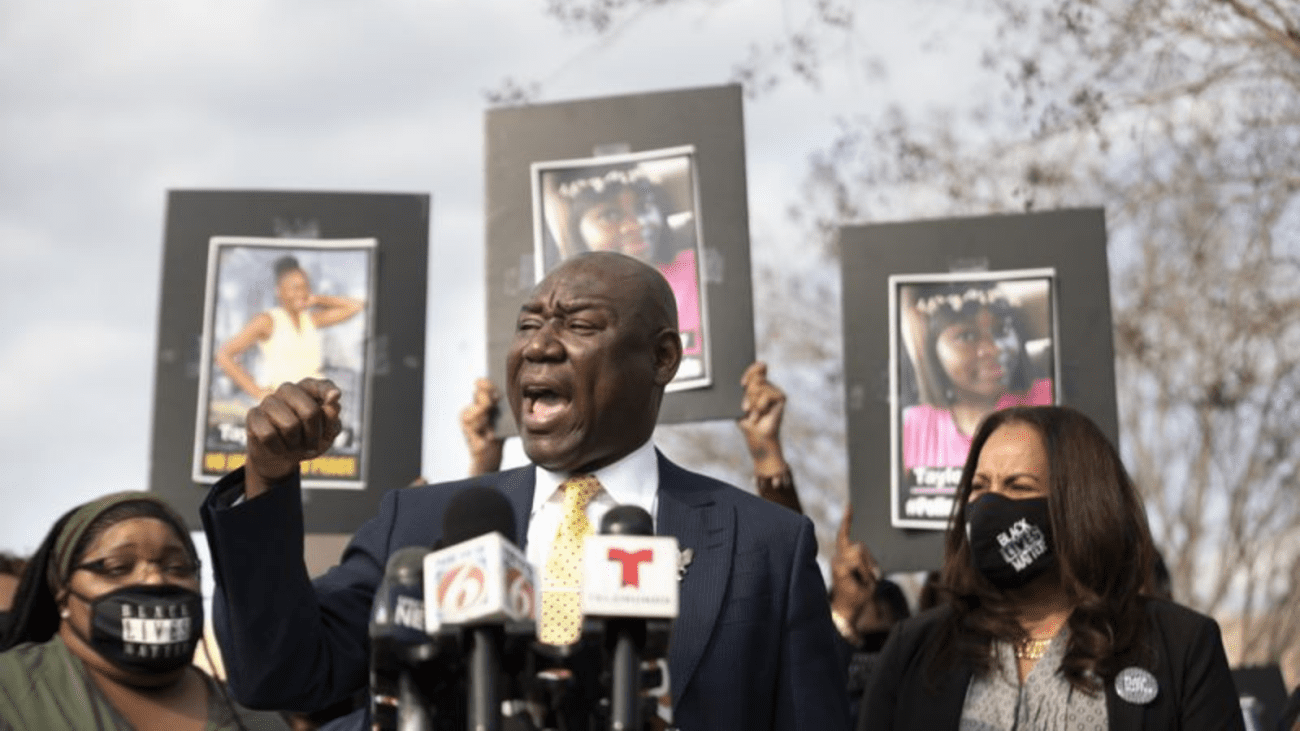

Photo: Renowned civil rights attorney Ben Crum speaks at rally in support of Liberty High School student Taylor Bracey who was slammed to the ground by a school resource deputy earlier this week. Crump is flanked by the victim’s mother, Jamesha Bracey, left, and civil rights lawyer Natalie Jackson, right, The rally was held outside the Osceola County Sheriff’s Office in Kissimmee on Saturday Jan. 30, 2021. (Orlando Sentinel Photo/Willie J. Allen Jr.) (Willie J. Allen Jr./Orlando Sentinel)