Critical race theory sparks debate in Hernando schools

Tampa Bay Times | By Jake Sheridan | August 26, 2021

Arlene Glantz’s evidence burst from her accordion folders.

Sitting before a crowd that had been promised proof of “critical race theory” in Hernando schools, she carefully stacked the public records she had requested.

The papers proved the school district is indoctrinating students, she said at an unofficial “town hall” that she’d set up with her husband, School Board candidate Mark Johnson.

“If we don’t speak up, if we don’t stop this craziness now, we’re gonna lose this country,” Glantz told the crowd.

The national controversy over a once little-known academic framework about race is playing out in the 23,000-student Hernando County School District, with the debate at times becoming a proxy for larger culture wars within the community and across the country.

School administrators have repeatedly said critical race theory — which is centered on the impact of legally codified racial discrimination in America — has never been taught in Hernando schools and won’t ever be. Officials in other Florida districts have made the same point, noting that the theory is largely a college-level topic.

Still, its recent emergence as a political issue has made Hernando County a case study in how issues like critical race theory, mask mandates and vaccinations have driven a wedge in many communities over the past year, at times becoming a platform for political candidates.

In June, the State Board of Education, following the lead of Gov. Ron DeSantis, moved to ban critical race theory from Florida schools, even though officials said it already wasn’t included in school curricula.

Some have criticized DeSantis’s efforts as a political attempt to “whitewash” and suppress discussions about race.

The discussion set off a series of spirited public meetings in Hernando County, with worried residents on both sides of the issue — with some feeling their children are being indoctrinated and others fearing the outcry could stifle equity efforts in the district.

Glantz and Johnson have been at the forefront of some of the debate. The couple, who spoke at a contentious School Board meeting earlier this month, alleges critical race theory is entering the school district through a plan to include more students in advanced courses and equity training programs for teachers.

Some Hernando County school district officials say the indignation is in part a political effort to get Johnson elected. Johnson was previously elected to the Hernando County School Board in 2014 but lost reelection in 2018.

“There are people here who want to make an issue out of something that doesn’t exist for their own benefit,” School Board member Jimmy Lodato said.

Trickle down

As over 70 people walked into the family center of Spring Hill’s Northcliffe Church for the town hall, they passed a sign-in table with Mark Johnson campaign stickers and a petition to get him on the ballot.

Johnson spoke first.

He called the “Equity in Education” training program used twice by the school a “Marxist” attempt to “create a rift for revolution” and “a scenario of oppressors versus oppressed.”

“That trickles down into the classroom,” Johnson said.

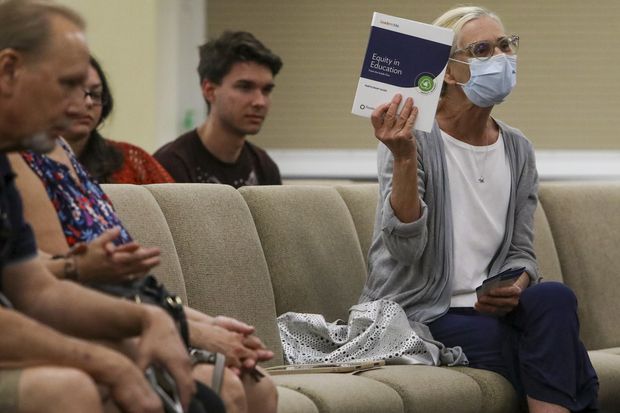

He and Glantz pulled examples from a manual that accompanied the training to present their case. Glantz, who confirmed the trainings took place by requesting records related to them from the school district, took particular issue with the manual’s use of the word “minoritized.” The word referred to students affected by “mistreatment and prejudice resulting from situations outside one’s control,” it said.

She raised the manual as she spoke, decrying its critique that teachers often unfairly hold unequal expectations of students, as well as its advocacy for collaborative, student-led learning.

She also took aim at the “Crucial Conversations” training that sought to teach educators how to have conversations about equity without offending others or becoming defensive. Then she criticized the school district’s effort to address achievement gaps among identity groups by including more students in Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate courses who might typically be considered unqualified.

“For the sake of equity, we are dumbing down the best and the brightest,” she said.

To Glantz, a focus on equity functions as a Trojan horse to get critical race theory into classrooms.

Murmurs of surprise and agreement flowed from most of the apparently all-white crowd as Glantz and Johnson spoke. A mic was passed around and listeners shared outrage and questions.

Susanne Dockery sat in the second row, holding her own evidence — another copy of the “Equity in Education” manual. As Glantz spoke, Dockery flipped through pages, eager to defend the training and argue critical race theory is not taught in Hernando schools.

When she got the mic, she, too, raised up the manual.

“This benefits every student,” said Dockery, who raised four kids in Hernando schools and now has two grandchildren in the system. “You meet them where they stand.”

She argued that the manual wasn’t just about race. Physically and mentally handicapped students, poor students and others deserve equitable treatment too, she said.

Glantz stopped her to respond, drawing applause from the crowd. Then Johnson cut in before moving on to another question. The couple requested donations to defray the $500 cost of running the town hall.

“It was nothing more than a political rally,” Dockery said afterward. “Fear sells. Critical race theory is a dog whistle.”

District officials push back

Hernando County superintendent John Stratton said he thinks some phrasing in the equity training program triggered the critical race theory claims.

“That’s not what equity in education means to those in education,” he said in an interview. “It’s bringing awareness to our staff that although everybody has equal access, not everybody has equal footing.”

The 82-page training manual includes three direct references to race or racism in its main pages, according to a Tampa Bay Times review of the document, including a prompt asking educators to reflect on if they were raised with a sense of racial identity. The manual broadly encourages educators to more deeply consider their students as individuals, noting that not everyone is served equally well by the school system.

The school district is required by the federal and state government to address achievement gaps among “subgroups,” defined by race, income, disabilities and language, Stratton said. Focusing on equity allows schools to make sure all students have equal access to education, he added, but it’s also mandated by law.

He argued that the effort to include more students in advanced courses doesn’t dumb down the courses because all students are still required to pass standardized tests.

Stratton said the district offered the “Equity in Education” training twice, once to a group of guidance counselors and social workers and another time to members of the district’s equity task force. The material shared with teachers isn’t critical race theory, he said, and also wasn’t directly taught to students.

During a recent contentious School Board meeting, at which about a dozen residents spoke to decry the training as critical race theory and a handful of others defended it, Stratton urged those with complaints to volunteer for the school system and see what goes on inside classrooms.

Stratton said no teachers complained to him about the training. Vince La Borante, president of the Hernando Classroom Teachers Association, said the same. Sign-in forms obtained by Glantz via a public records request show 65 teachers attended the training.

“It’s extremely important that you get to know your students, get to know your students’ backgrounds,” said La Borante, who taught for 35 years.

Pam Everett, a student resources advocate and School Board candidate who has also criticized the equity trainings, said more than 45 teachers have complained about the training to her, although she didn’t provide names.

“All the kids are the same. When you’re pointing it out, you’re causing a divide,” Everett said.

Board member Lodato said the equity training program was about lifting up all students, not creating racial divide. The program helps teachers learn how to treat people with kindness and move past preconceptions, he said. He couldn’t find any instances of critical race theory.

“I read the book and I questioned all the teachers. That is not what it is,” Lodato said. “They’re making an issue that doesn’t exist here.”