Florida now leads the country in book bans, new PEN report says. How did that happen?

Miami Herald | By Amanda Geduld | September 21, 2023

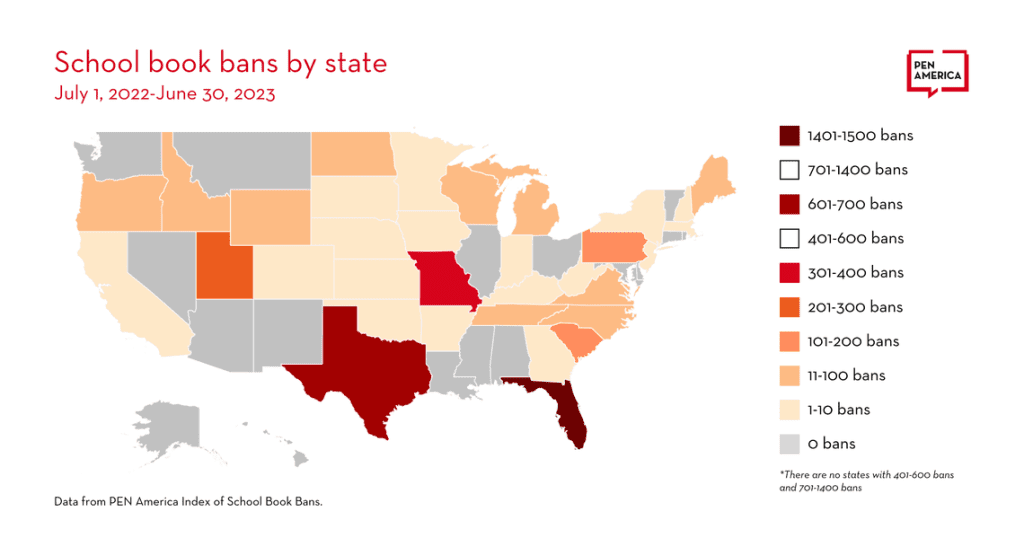

More books were pulled from shelves in Florida public schools compared to any other state during the past school year, a new report released Thursday by PEN America found.

The nonprofit, which advocates for freedom of expression, recorded 3,362 instances of bans in public school classrooms and libraries from July 2022 to June 2023 across the country. Out of these, about 1,400 — or 40% of the national total — took place in Florida.

“Florida is not an aberration,” said Tasslyn Magnusson, a consultant with the Freedom to Read team at PEN America. It’s the direction a number of other states appear to be headed as well, she said.

Magnusson noted that Florida is the perfect example of “everything that’s happening all at once: there’s group influence. There’s legislative influence. There’s people who are worried and scared and unsure of how to move forward in a way that supports kids.”

About 1,400 book bans took place in Florida from July 2022 to June 2023, a new report from PEN America found. These accounted for 40% of national book bans.

Texas registered the second highest number of book bans with 625 books banned, followed by Missouri (333), Utah (281) and Pennsylvania (186).

The nonprofit defines a “book ban” as “any action taken against a book based on its content, and as a result of parent or community challenges, administrative decisions, or in response to direct or threatened action by lawmakers or other governmental officials, that leads to a previously accessible book.”

Most book bans recorded this past year are currently classified as “banned pending investigation,” meaning the book has been removed during review. Kasey Meehan, PEN America’s Freedom to Read program director and lead author of the report, said in a press release that exaggerated and misleading rhetoric continues to ignite fear over the types of books in schools.

“Florida isn’t an anomaly — it’s providing a playbook for other states to follow suit. Students have been using their voices for months in resisting coordinated efforts to suppress teaching and learning about certain stories, identities, and histories; it’s time we follow their lead,” Meehan said.

WHY ARE BOOK BANS ON THE RISE?

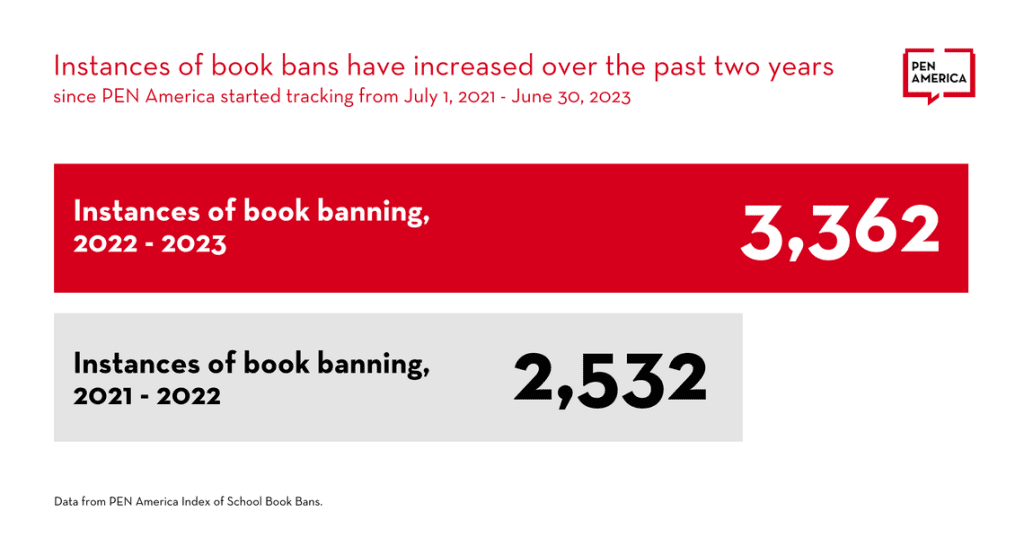

Nationally, book bans shot up by 33% from 2,532 in the 2021-22 school year to 3,362 in the 2022-23 school year, the report titled “Banned in the USA: The Mounting Pressure to Censor” shows.

Instances of book bans have increased over the past two years. In the 2021-22 school year, there were 2,532

instances of book bans. In 2022-23, there were 3,362 instances, PEN reports in a study released Thursday. And while the report points to vaguely worded state legislation and pushes by local and national advocacy groups as some of the reasons for the increased book bans, the 18-page report also highlights how laws and tactics used in Florida in recent years are being replicated elsewhere.

One example in Florida is the expanded “Parental Rights in Education” law, signed into law by Gov. Ron DeSantis last year and dubbed by critics the “Don’t Say Gay” bill as it prohibits discussions of sexuality and gender identity from kindergarten through third grade.

In this year’s session, state lawmakers expanded the restrictions through the eighth grade. The expanded law, which DeSantis signed, also allows a parent or community member to object to instructional material or library books, and requires a school to remove the book or books within five days of a challenge and remain off library shelves until the review is completed.

The process is a “guilty until proven innocent policy” that leads to the removal of more books for more time, said Raegan Miller, director of development at the Florida Freedom to Read Project, a nonprofit that advocates for school libraries being accessible to all students.

Moreover, she said, books are expensive to purchase and public libraries are not accessible to all students — especially young students whose parents are unable to accompany them.

BOOK RESTRICTIONS IN MIAMI-DADE AND BROWARD SCHOOLS

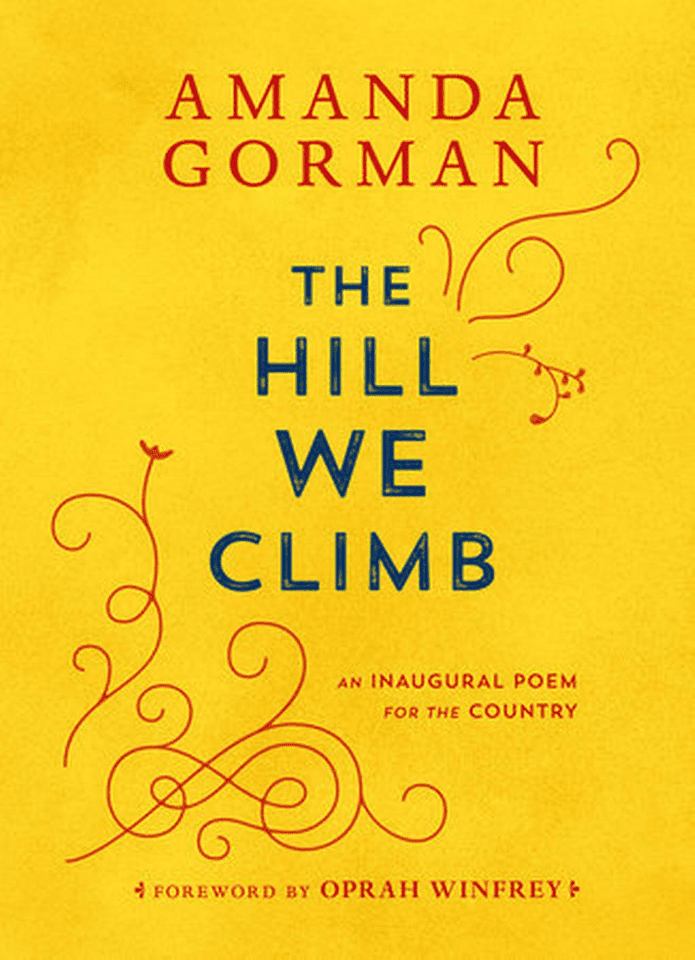

Locally, Miami Dade Public Schools received six challenges in the 2022-23 school year, up from zero last year, as previously reported by the Miami Herald. The school district rejected two challenges, and after one parent complained about a series of titles, three were restricted only to the middle school students at that school, Bob Graham Education Center in Miami Lakes. Among the works restricted: the poem “The Hill We Climb,’’ written and recited by Amanda Gorman during President Joe Biden’s inauguration on Jan. 20, 2021.

Cover of Amanda Gorman’s book containing the inaugural poem “The Hill We Climb” and a foreword by Oprah Winfrey. The Bob Graham Education Center in Miami Lakes, a Miami-Dade public school, put the book on a restricted list during the 2022-23 school year after a parent complained about it. Penguin Random House

The Broward school district received 12 challenges in the 2022-23 school year, up from one last year. The challenges resulted in three books being banned for all students and nine books restricted to specific grade levels.

Desantis, who has championed the bills, has called the “whole book ban thing” a “hoax.”

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis called book banning in Florida a ‘hoax.’ He is shown at a rally in Clay County in Florida in March, where he unveiled a civics program in the state’s public schools. Facebook

During his May 24 presidential campaign launch on Twitter Spaces, he said, “there’s not been a single book banned in the state of Florida. You can go buy or use whatever book you want.”

“What we have done is empowered parents with the ability to review the curriculum, to know what books are being used in school, and then to ensure that those books match state standards and are age and developmentally appropriate,” he added.

BOOK BANNING CAUSES CHILLING EFFECT AMONG EDUCATORS

Most targeted books were written for younger audiences, the PEN America report says.

Almost half include themes or instances of violence and abuse, including sexual assault. About 40% cover topics on health and well-being for students, including mental health, bullying, substance abuse and puberty. About one-third of the books include LGBTQ+ characters or themes, and about one-third discuss race or include characters of color, according to the report

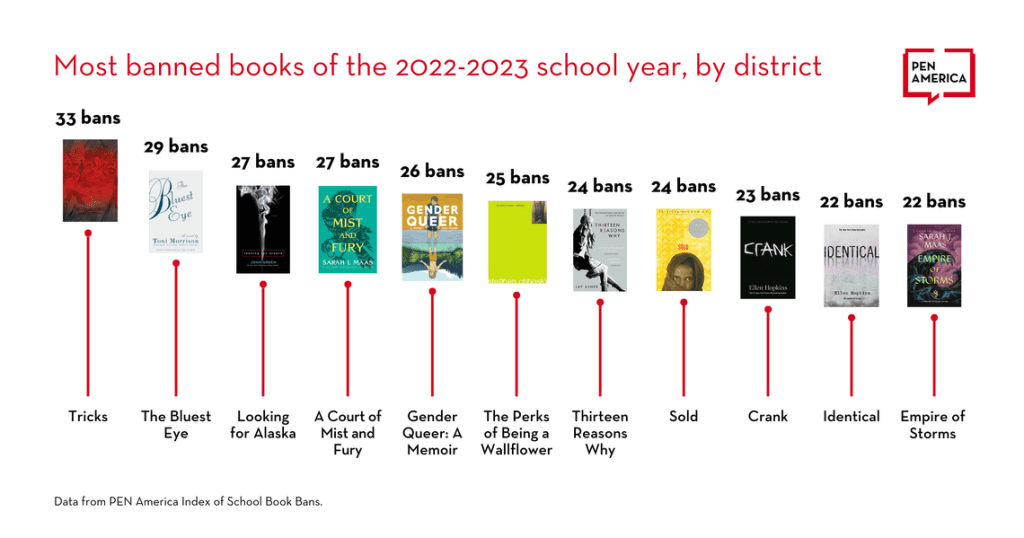

Nationally, ‘Tricks’ by Ellen Hopkins was the most banned book, with 33 bans total.

In the more than 150 school districts that banned a book during the 2022-23 school year, the vast majority — 80% — have a chapter or local affiliate nearby of one of three groups that have been instrumental in book bans: Moms for Liberty, Citizens Defending Freedom, and Parents’ Rights in Education.

The report highlights the role of BookLooks, a website founded by a former Moms for Liberty member, which provides users with ratings of books alongside reviews that often include the most controversial passages.

Supporters say these groups give parents more of a voice in their child’s education and ensure children are not exposed to age-inappropriate materials. Critics argue the site provides people with the tools to challenge a book without ever having read it.

“The unfortunate result from this mounting, multifaceted pressure is that the very stories and voices that have been traditionally underrepresented on school shelves are continuing to be removed at ever-increasing rates,” the report said.

Miller, of the Florida Freedom to Read Project, echoed the findings, arguing the vague language of these laws, including the “Parental Rights in Education” bill, means that they are often applied differently in different districts and as a result, books are often removed without going through the formal challenge process.

“I’m willing to bet that the PEN report doesn’t really even scratch the surface of how many books have been removed,” said Miller. “Because there’s no way for us to capture how many teachers just decided, ‘You know what? I’m not gonna sit here and scan in every book.’”

Still, for Magnusson, the consultant at PEN America, what’s most striking is how tired educators are.

“It takes great resilience for librarians and educators to continue to fight for titles in light of confusion… so they’re going to choose easier titles that won’t challenge kids and won’t expose them to diversity, because it’s so hard.”

Magnusson also emphasized the resilience of parents and students fighting for education and access to books.

“Florida has a huge uphill climb. But there are communities across Florida who are striving to push back to ask for inclusive literature. They just aren’t heard as much.”