Harsh Florida law sees more Black kids tried as adults than white kids

Miami Herald | By Shirsho Dasgupta, Clara-Sophia Daly and Devon Milley | June 27, 2024

As a teenager, Naqwan Watson dreamed that playing football would allow him to escape his rough neighborhood in Miami Gardens. It had propelled his hero Chad Johnson from a tough upbringing in Liberty City to a Pro Bowl career with the Cincinnati Bengals.

But Watson’s hopes came to an end one afternoon in 2009.

Watson, then 16, and a friend forced their way into a Plantation home armed with a gun, fought with one of the residents and made off with a video camera and cellphone worth $575. It would cost him 20 years of his life.

Watson is one of thousands of children in Florida who have been tried as adults in the last three decades under a state law — “direct file” — that gives prosecutors unfettered discretion to remove children from the juvenile system and try them under the harsher penalties adult offenders face.

In 2011, the U.S. Department of Justice concluded that Florida’s “expansive” law played a major factor in making the state a “clear outlier” nationally in the rate of children tried as adults. At the time, roughly one in 10 children in the juvenile system were tried as adults.

While fewer kids today are moved to the adult system than at the time of the DOJ’s findings, the decline in these cases has not benefited all accused juvenile offenders equally, a Miami Herald investigation found.

Black kids like Watson make up a disproportionate — and growing — share of the children whose cases have been moved to adult court, according to the most recent 15 years of data available. The share of children transferred to the adult system who were Black has steadily ticked up from around 58% in 2008 to roughly 65% in 2022, the Herald found.

Adjusting for the type and number of charges children faced, the Herald found that Black kids were roughly two times more likely to be transferred to adult court than white kids.

Miami-Dade and Broward counties had the highest share of minority children charged as adults over the last 15 years.

Florida’s juvenile system, plagued with instances of excessive force, sexual misconduct, psychological abuse and inadequate medical care, is hardly a cakewalk. But it is still geared toward rehabilitation rather than punishment, legal experts told the Herald.

After conviction in adult court, minors typically have to deal with harsh prison conditions and the consequences of having a felony record for the rest of their lives. They are released into society as adults after spending crucial developmental years behind bars with limited access to education and training on the basics of how to live as independent individuals. They struggle to find jobs and housing, often end up committing offenses again – and the cycle continues.

Because children and teens are still developing reasoning skills, they are inherently less responsible for their behavior than adults, several psychologists said. Serving time in an adult prison, with its more punitive approach, can also harm their development and have a lasting impact on their ability to reenter society.

Between 2008 and 2022, Florida charged around 20,500 kids in adult court. Around half were charged with only nonviolent offenses. Three out of four of the children came from minority communities. Many are still serving their sentences.

“For young people who are in the process of development and haven’t fully learned social skills … this is an experience that damages their maturation,” said Craig Haney, a psychology professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who has spent more than four decades studying the psychological effects of incarceration.

“It’s a terrible idea to put a juvenile in an adult institution.”

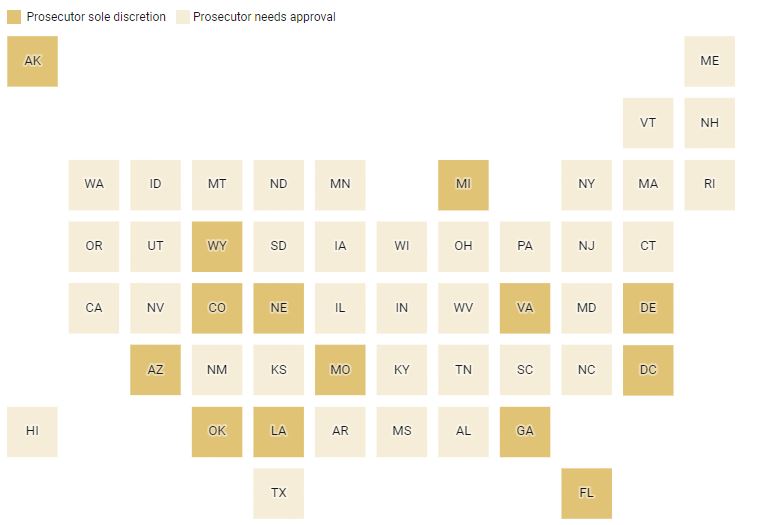

States which let prosecutors try kids as adults

13 states and D.C. allow prosecutors to charge kids as adults without a judge’s approval

Jack Campbell, state attorney of the Second Judicial Circuit based in Tallahassee, acknowledged the racial and economic disparities in terms of which children are moved to the adult system but defended the value of the law, which he said was an “important tool” for prosecutors.

“Some crimes and some criminals cannot be adequately handled by the juvenile system,” he said.

For juvenile cases, a minor’s record is expunged after they age out of the system. That’s not the case for adult charges, which come up in background checks even if a person has not been convicted, making it hard for accused offenders to find work, build a career or find housing.

Florida enacted its “direct file” legislation 30 years ago and has persisted with the practice even while several other states have moved away from it, juvenile crime rates have fallen and numerous studies have shown that imprisonment increases the chances of delinquent children — most of whom come from poor backgrounds — becoming repeat offenders.

When adjusting for the type of offense, Black children over the last 15 years were:

- Nearly 20% more likely to be tried as adults than white kids for property damage

- Fifty percent more likely to be sent to adult court four assault and battery than white kids

- Three times more likely be tried in adult court for drug offenses than white children

The Herald’s analysis did not account for prior arrests or detention that did not lead to formal charges since juvenile records are confidential and expunged after children turn 18.

To understand the impact of the laws, the Herald spoke with dozens of Florida inmates currently serving time after being transferred to the adult system, kids and families going through the legal process now, and adults released from detention after being tried as adults when they were still minors, as well as roughly 50 legal experts specializing in criminal law.

Over the course of a year, Herald reporters analyzed data on juvenile cases prosecutors transferred to the adult system, filed around 70 records requests, reviewed hundreds of pages of arrest reports and legal filings, attended court hearings and watched hours of footage of court proceedings.

“It’s tragic — what it means is that young African Americans are being subjected to these damaging experiences at high rates, and some of them are likely to be permanently damaged,” Haney, the psychology professor, said of the Herald’s findings.

“It’s a manifestation of widespread implicit racial bias that plagues not just the American public but decision-makers and the legal system as well.”

FROM POVERTY TO PRISON

Watson, the first-generation American son of a Bahamian mother and Jamaican father, found refuge from his tough Miami Gardens neighborhood through football, baseball and track and field.

But like many children who wind up in the juvenile justice system, he encountered traumatic events at a young age.

When he was only 8, federal agents wearing ballistic vests and carrying “high-powered rifles” kicked in his grandmother’s door at 4 a.m., held Watson, his grandmother, mother and siblings at gunpoint, and demanded to know the whereabouts of his uncle, who was facing drug charges.

That experience colored his views of law enforcement, he said.

His father was sentenced to federal prison on drug charges before Watson turned 10 and was deported back to Jamaica for not having proper immigration paperwork after being released. Watson’s older brother also went to prison on drug offenses, leaving no positive male role models for Watson as a child, he said.

Watson’s first brushes with the law were for minor juvenile offenses. He was once charged with theft for stealing a friend’s dirt bike — an allegation he denies — and sent to juvenile custody on another occasion for getting into a fight. He was never referred to prolonged detention, he said.

That would soon change.

As Watson tells it, it was not his idea to break into the Plantation home one afternoon in July 2009. Watson, then 16, said he wanted to support his friend.

“He said he got no money,” Watson said. “I felt obligated.”

The man who answered the door initially fought with them, before Watson pointed a gun at him, according to the arrest report. None of the occupants were physically harmed in the robbery, but Watson and his friend made off with a video camera and cellphone worth a total of $575.

Broward prosecutors moved Watson and his friend to adult court and charged them with home invasion and grand theft.

Watson entered a no contest plea in 2010, meaning he did not admit guilt but also did not dispute the charges, which has the same immediate effect as pleading guilty.

He was only 17 when he entered Florida’s prison system and will be 34 when he is scheduled to be released.

“If somebody does something, they should be penalized — I understand that,” Watson said. “But give them reasonable penalties.”

WHERE FLORIDA STANDS

While differences in state laws and data collection methods make it hard to compare Florida to other states by the numbers, the parameters of Florida’s law make it among the harshest in the country.

Depending on the offense, children as young as 14 can be tried as adults in Florida — among the lowest minimum ages in the country, a Herald review found. It is also one of only three states and the District of Columbia that don’t allow children to be sent back to the juvenile system by an adult court once they have been transferred via this law — even by a judge.

In states without these laws, prosecutors must seek approval by a judge before charging a child as an adult.

A kid charged as an adult in Florida is treated as one for all charges pending trial and all subsequent offenses — once an adult, always an adult.

The only power the laws give judges is over the child’s sentencing. Judges can be lenient and impose “juvenile sanctions,” meaning the minor will have an adult felony record but will serve their sentence in a juvenile facility instead of an adult prison. Judges can also designate a child as a “youthful offender” and put them on probation or send them to a military-style boot camp with other convicted young adults for a maximum of six years.

But judges typically did not go for these options in the cases reviewed by the Herald.

Children and families who spoke with the Herald, many of whom come from poor backgrounds, said they were frequently overwhelmed by the complex legal process, and sometimes didn’t even realize that their cases were being tried in adult court.

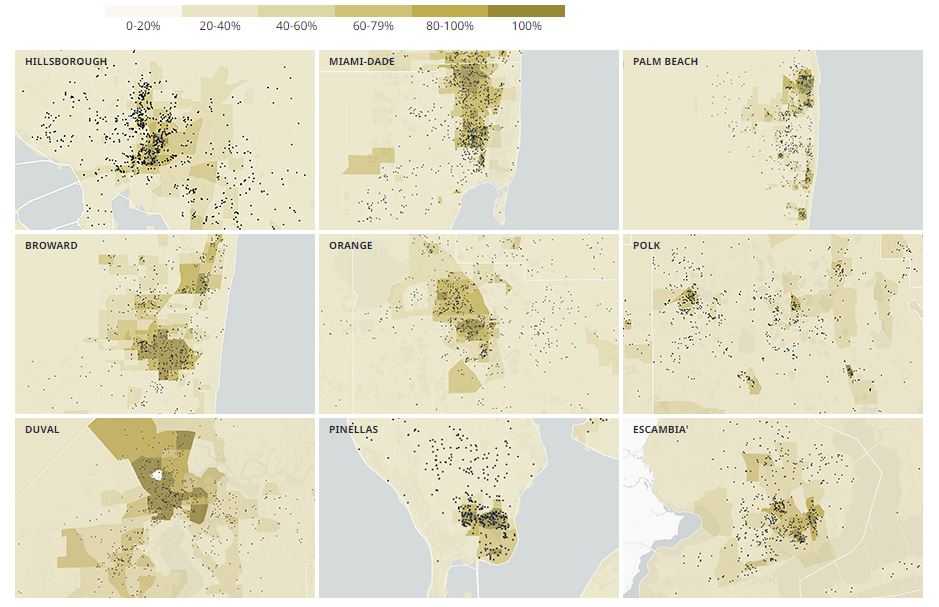

The number of kids tried as adults has decreased in the judicial circuits that represent Miami-Dade and Broward counties. But a disproportionate number of the children who have faced adult charges in these counties come from communities of color, making Miami-Dade and Broward the two judicial circuits in the state with the highest share of minority children tried as adults.

Although roughly 84% of the kids residing in Miami-Dade belong to minority groups, around 98% of the approximately 1,850 kids prosecuted as adults in the county from 2008 to 2022 were from communities of color. In Broward County, where around 70% of the resident kids are minorities, roughly nine out of every 10 kids tried in the adult system there in the same period were from minority communities.

Where kids tried as adults were arrested Most of the arrests were in majority-Black neighborhoods

Each dot represents the location where a child tried as an adult was arrested Black percentage of juvenile population by census tract

Source: Florida Department of Juvenile Justice, U.S. Census Bureau • Map: Susan Merriam

The state attorneys’ offices in Broward and Miami-Dade counties said they consider factors like the nature of the charges, a child’s record of prior offenses and whether a child is about to turn 18 when deciding whether to try a child as an adult.

The Broward state attorney’s office said in a statement that since 2021 the office has required a “panel of prosecutors” to review each potential case before making a decision. The number of children Broward’s prosecutors have tried as adults has steadily decreased in recent years, but racial disparities have persisted. All 10 of the children tried as adults in 2022, the most recent year available, were Black.

The office did not answer specific questions about racial disparities in which children are tried as adults.

Ed Griffith, a spokesperson for the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office, said that the office has greatly reduced the number of children it moves to the adult system and introduced a civil citation program for juvenile offenders.

“We make every effort to keep a case in the juvenile court system,” he said.

He dismissed the Herald’s findings about racial disparities as “misinformed” and attributed the high share of minority kids tried as adults to the demographics makeup of those who are arrested in the county.

“If there are no white males charged … with murder or manslaughter, no white males will be direct filed … with that charge,” he said.

The Herald’s analysis found that Black children arrested in Miami-Dade were around 50% more likely to be tried in the adult system than white kids, even when adjusting for the type of offense.

Melba Pearson, a former Miami-Dade prosecutor, said that fixing these racial disparities requires more than just a change in the individual decisions of prosecutors and judges, but requires solutions to broader societal issues such as lack of opportunity and resources in many heavily minority communities.

“If you see people falling in the river, you have to go upstream to figure out what’s happening, right?” she said.

‘DISTURBING TO ONE’S SOUL’

De’Neair Stanley can still remember the smell of baked chicken, beans and lemon cake coming from his mother’s kitchen. He remembers going on fishing trips to Lake Jesup in Seminole County in central Florida with his grandfather. A fan of hip-hop and rap, he would often record his own songs at his uncle’s studio when he was in his early teens.

But Stanley, now 30, is a long way from those carefree days.

The smells of “cigarettes and urine” dominate the prison block he now calls home. Solid brick walls reinforced by steel rods with no air conditioning offer little protection from the outside elements, be they bone-chilling winter nights or the blazing heat of summer days. There’s nothing fresh, or appetizing, about the processed food he eats. Depression and anxiety haunt him.

Early into his time at Jackson Correctional Institution in the Panhandle, Stanley witnessed one inmate slice the face of another while they waited in line for lunch, he said. Blood spurted out.

That night, Stanley, then still a teen, wondered whether he would even come out alive.

Stanley grew up in a poor, majority-Black neighborhood in Orlando, and by his own telling was often “reprimanded by teachers for being disruptive.” He started smoking weed in eighth grade and at times skipped school at Maynard Evans High sC. After being released, he started spending time with older friends.

These new relationships would change his life.

On June 10, 2012, Stanley and two of his new friends drove down to Sunrise in Broward County in a rented Dodge Charger. Around noon, they robbed a convenience store at gunpoint, taking $300 and a Monster Energy drink. No one was hurt.

Sunrise police officers tracked them down and arrested them later that day.

Shanitha Grissom, Stanley’s mother, still remembers getting the call about his arrest at 2 in the morning: “At that moment, I felt like my whole world was crashing down on me.”

Shanitha Grissom holds a photo of her with her son De’Neair Stanley, made during a recent visit at his prison, Wednesday, June 12, 2024 in Winter Park, Fla. (Phelan M. Ebenhack for the Miami Herald) Phelan M. Ebenhack

During his interrogation, Stanley, then 17, told a detective that he was “in fear of being killed for speaking out against those involved in the armed robbery” and asked the officer “not to use his name” in any documentation, per his arrest report.

Broward County prosecutors transferred him to the adult system on armed robbery charges roughly a month later.

Stanley told the Herald that the robbery had been the brainchild of one of his two friends, who was in his early 30s at the time and said he needed money. That friend stayed in the car, while Stanley and the third friend, in his early 20s, entered the store.

Both threatened the store clerk with guns, but Stanley was the only one to face consequences for the robbery. Prosecutors noted there was “insufficient evidence” to prove the involvement of Stanley’s friend who had stayed in the car and declined to charge him, case notes obtained from the state attorney’s office show. The other pleaded mental incompetence, leading to his case being dismissed.

Stanley was held in a Broward County jail during the trial and two years later, in February 2014, entered a no contest plea. The minimum sentence for Stanley’s charges was 10 years, but he was sentenced double that, with an additional 10 years of probation.

Stanley asked the judge for leniency and to be classified a “youthful offender” because he had no prior criminal record. The judge denied both.

Stanley still vividly remembers his transition from civilian to inmate. He stood in line for hours during prison intake before it was his turn to undress, squat and spread his buttocks for a security check.

“They strip you of all dignity and humanity,” Stanley told the Herald. “It’s disturbing to one’s soul.”

His days now follow a grim routine. He’s up at 4:30 each morning for breakfast and works from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. collecting trash from nearby parks and forests. Every month he works buys him a 10-day reduction to his sentence. He is closer to home now, in Sumter, which is an hour from Orlando but still has eight years to go before his release.

“To our loved ones we’re somebody. A son, brother, father, nephew, uncle, and friend. To them we still hold value,” Stanley wrote in an online blog last year. “To the system we’re the scum of the earth.”

TOUGH LOVE

Florida’s law traces its roots to a crime surge in the late 1980s and early 1990s that led to the theory of the “super-predator.”

The term, coined by John DiIulio Jr., then a Princeton University professor, described a new breed of “morally poor” urban teen criminals, born to parents with addiction issues, who would go on to murder, rape, rob and deal drugs. He predicted that half of these “super-predators” would be Black.

The idea gripped the nation.

Endless versions of political TV ads with candidates touting their tough-on-crime credentials played in living rooms across the country. Lawmakers increased punitive measures and expanded the range of charges under which kids could be tried as adults.

The crime wave hit home in Florida.

Nine foreign tourists were killed over 11 months in 1992 and 1993, including two who were shot by kids in their mid-teens, threatening the state’s place as a sun-kissed tourism Mecca.

Headlines screamed “Sun ‘N’ Guns: Florida crime surge rocks Canadians,” “Fear of Florida the latest phobia: State officials are as worried as the tourists,” “State of terror: Florida killing spoils Disney World dream for a million holiday Brit.”

Florida legislators passed the Juvenile Justice Reform Act in 1994 in response, creating the Department of Juvenile Justice and moving away from the state’s previous rehabilitative model under the Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services. It also expanded prosecutors’ power to try kids as adults based on their discretion rather than a judge’s decision.

The state had had similar laws since the late 1970s, but they had been restricted to kids with extensive records of violent felonies. Under the new law, prosecutors could try any child aged 14 or 15 as adults for murder, some sexual crimes, robberies, and certain types of burglaries and thefts. They could also transfer 16- or 17-year-olds to the adult system on any charge if they deemed that “public interest requires that adult sanctions be considered.”

But the feared super-predators never came.

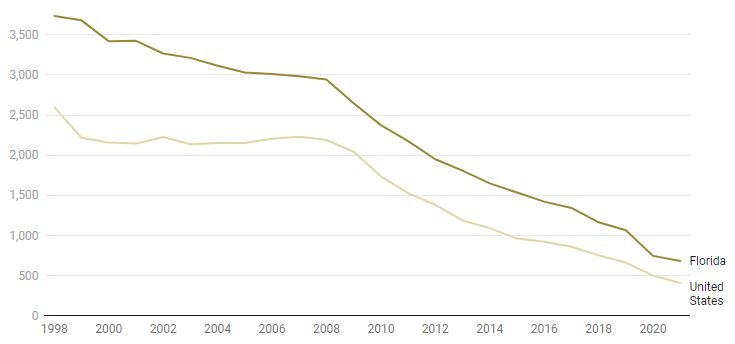

By the time the laws started being enforced, juvenile arrest rates — a key indicator of crimes committed by minors — started falling, and they have continued to fall in the subsequent decades, both in Florida and other states without harsh penalties for delinquent kids.

Florida officers arrested juveniles at a rate of 3,700 kids for every 100,000 children in the state in 1998, according to data from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. In 2021, the most recent year for which arrest figures are publicly available, that rate stood at roughly 700 per 100,000 children.

Juvenile arrest rates have fallen nationally over the last two decades

But Florida’s juvenile arrest rate is higher than national numbers

The figures show the rate of children arrested (per 100,000 kids) Chart: Madeline Everett Source: Florida Department of Law Enforcement, U.S. Department of Justice

Numerous criminologists the Herald spoke with said that the decline in juvenile arrests is not because of Florida’s harsh penalties. Kids are rarely aware of the law, they said, and juvenile crime has declined even in states with less punitive laws.

“If the fact that we are transferring kids and punishing them harshly was truly working as a deterrent, then you wouldn’t expect to see the same trends in states that did not pass or expand transfer laws — but that’s not what we’re seeing,” said Todd Warner, a psychology professor at the University of Miami who has extensively worked on juvenile justice policies.

Experts say the falling juvenile crime rates are more likely due to policy factors like increased support for rehabilitation and diversion programs. Sociological factors, like decreasing alcohol consumption by children and the easy availability of video games and the internet, which keep kids in more supervised settings, have also likely contributed, said Kelsey Cundiff, a criminology professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis who specializes in adolescent delinquency.

As juvenile arrest rates plunged, states like California, Colorado and Vermont, all of which had laws similar to Florida’s statutes, moved away from the punitive approach of trying kids as adults.

Reform advocates have pushed to repeal Florida’s law multiple times. They have also pushed to change the law to give children a hearing before a judge to determine whether they are charged as adults, rather than the current rules which give prosecutors sole discretion over whether to try juvenile offenders in adult court.

But those attempts have failed, most recently in 2019, and Florida has persisted with its harsh penalties. For children like Watson and Stanley, the impact has been life-changing.

UNCERTAIN FUTURES

It’s the only way he’s found to make a living since being released from prison in 2020.

Milien, the son of Haitian immigrants, grew up in a working-class North Miami Beach neighborhood. His house was just a stone’s throw from the local police station, and officers would often harass him and his friends when he was growing up, both Milien and his mother, Marie, told the Herald.

Miami-Dade prosecutors tried Milien, then a 15-year-old student at North Miami Beach Senior High School, in adult court on home invasion charges for breaking into two neighborhood homes in 2010.

“I was still young, it didn’t really hit me,” Milien said. Marie, a Haitian-Creole speaker with passing English, did not even realize that her son had been tried as an adult before the Herald spoke with her.

Milien served two years in prison. He was arrested again in 2016, during his four-year probation term, for shoplifting from a local Walmart and resisting security and was sent back to prison.

He applied to numerous jobs after his release four years ago, including at Amazon and UPS, he said. But none would hire him because of his felony record.

“I’m in the real world now, and it’s like, damn, I can’t really do nothing with this burden on my back,” said Milien.

Convicted felons like him face nearly 1,900 restrictions and other consequences under state and federal law even after regaining freedom, according to the Herald’s review of regulations collated by the National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction, a Justice Department-funded project.

Having a conviction can make it hard to obtain a professional license, make it tough to win child custody rights, limit access to public benefits and housing, and put some state scholarships off limits. Banks, property owners and other private companies often have their own additional restrictions on employing, renting housing to or providing services to those with criminal records.

An aerial view of the Broward Sheriff’s Office and the Broward County Judicial Complex on Friday, May 24, 2024, in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Matias J. Ocner mocner@miamiherald.com

De’Neair Stanley, who was arrested in the Broward convenience store robbery, has completed his GED during his time in prison and hopes that when he is released he can return to music and be a motivational speaker to encourage kids not to get “misled and misguided.”

But anxiety about the future persists for Stanley, who has spent his entire adult life behind bars and wonders if he will be able to survive as an adult in a world that has changed dramatically while he’s been stuck inside staring at the same brick walls.

“I’ve never paid a bill, I’ve never really been on my own. … I’ve never filed taxes,” he said.

“What’s the world going to be like by the time I come home?”