‘I see myself in these students’: 20,000 immigrant children join Miami-Dade schools

WLRN | By Kate Payne | May 24, 2023

For the first time in two decades, the Miami-Dade County public school system is growing, according to district officials.

That’s due in large part to the historic number of students who have moved into the district this year from other countries. Schools that had been under capacity for years are now seeing their classrooms fill up.

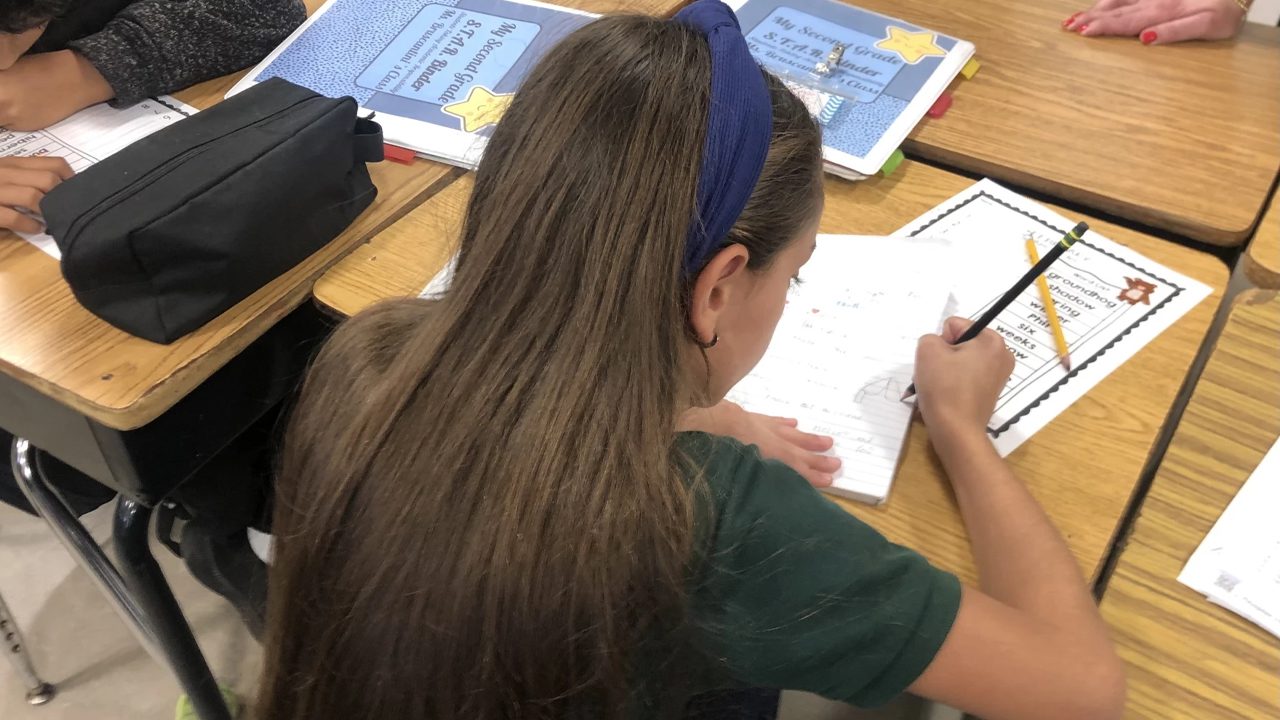

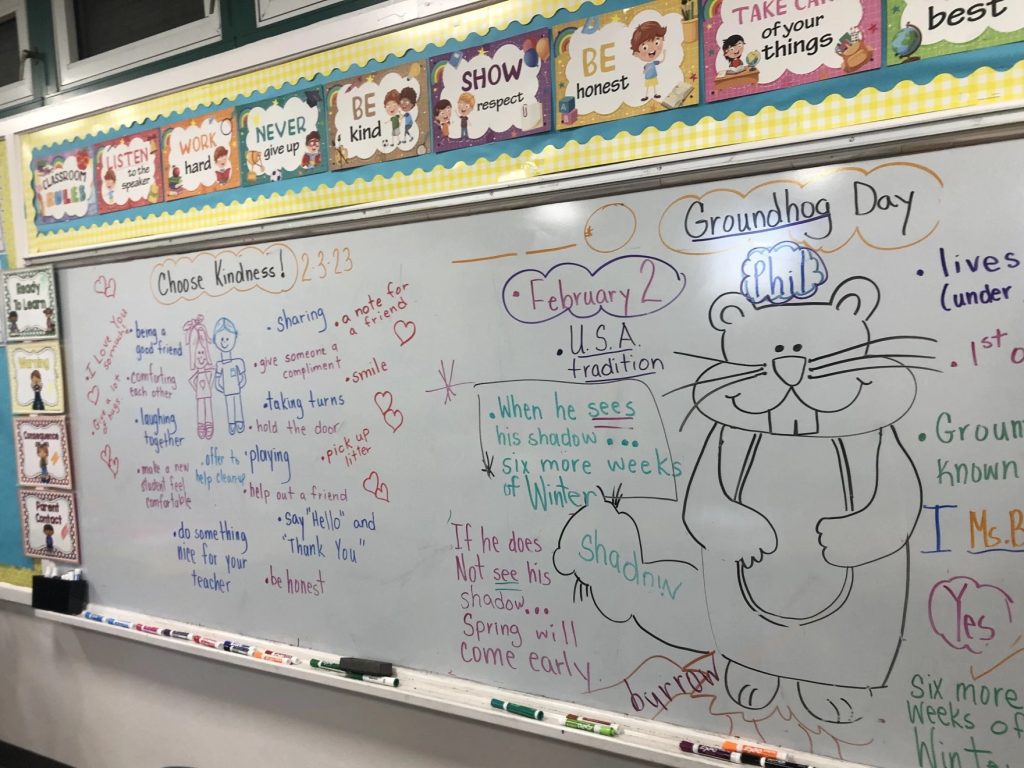

On a recent morning, Emelia Bruscantini’s classroom at Milam K-8 Center was calm and quiet, her students working diligently on math problems — some in English and some in Spanish.

“We just have one new [student] this week,” Bruscantini said. “Just came in Tuesday. Another one that came in last week, she went to the doctor to get her shots today.”

The majority of the district’s new immigrant students are from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela. A new Biden administration program allows people from those four countries to stay legally and work for two years — an effort to incentivize migrants to not make the dangerous trek to cross the U.S.-Mexico border.

Over the course of this school year, 20,000 new immigrant students have enrolled in Miami-Dade County Public Schools, according to district data.

That’s a much bigger influx of new students than the district saw immediately after Hurricane Maria — or after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

“Some of these kids didn’t know their ABCs in second grade,” Bruscantini said. “Remember COVID … some of them in their own countries couldn’t go to school. So we have to kind of go down to their level so that we can add skills to what they know. Because if not, they don’t get the basics.”

Schools address trauma, basic needs

Milam K-8 had been under-enrolled for a decade. This year, enrollment has hovered around 1,000 students — nearly at capacity.

Kate Payne / WLRN /

Principal Anna Hernandez says she’s never seen a spike like this one.

“Honestly … sometimes, I come into the lobby and there’ll be … the families are all over the place. Just waiting,” Hernandez said.

When families file into the front office at Milam, one of the first things they do is talk to a school counselor, like Lorena Liscano.

“We like to meet with the families and we like to get a little bit of a family history and kind of ask where are they living? What resources do they have? What resources do they need? And how can we help them?” Liscano said.

Liscano said many of the new families at Milam don’t have a home of their own. Under federal law, the school district has to support students who qualify as homeless.

“They can now get free breakfast, free lunch. They can get transportation. They can get school supplies, uniforms, clothing, groceries,” she said.

“We’re talking about their trauma. We’re discussing different things that they’ve experienced, trying to help them cope with losses they’ve had, with anxiety that they’re feeling.”

Many of the new students are getting weekly counseling too, Liscano said.

“We’re talking about their trauma,” she said. “We’re discussing different things that they’ve experienced, trying to help them cope with losses they’ve had, with anxiety that they’re feeling.”

Principal Hernandez says the rivers and oceans her students crossed to get to South Florida are still washing over them.

“I was talking to a teacher the other day and she was telling me how one of her students was sitting to take a test. He just didn’t seem like he was engaged at all. And then he started telling her how, when he was coming [to the U.S.], he had to go through a river. And it was almost like up to his face,” Hernandez said. “She was like, ‘You know what, I can understand why he’s not engaged in taking a test right now.’”

Many of the new students simply need more support — at a time when the district was already struggling to hire enough teachers.

Miami-Dade seeks additional funding to support immigrant students

“It certainly puts a stress on our finances,” said Ron Steiger, the school district’s Chief Financial Officer.

Steiger says the district was short changed $10 million dollars for these students. This school year, local officials went to Tallahassee and Washington, D.C. to lobby lawmakers for more support.

Since most of the students don’t speak English as their native language, they should qualify for extra funding from the state. But there were so many, they exceeded the state’s cap on how many English language learners a district can get extra money for. This session the Legislature removed that cap.

“The district is certainly prepared to deal with a lot of growth. We have the seats available,” Steiger said. “Prior to the early 2000s, we had 125 years straight of growth.”

While many of the new students need extra support, Steiger says they’re helping the district chart a new path forward — by increasing enrollment.

“We lost enrollment in our schools every single year for 20 straight years. But this year we didn’t. This year we went up,” Steiger said. “If not for those [immigrant] students we probably would have gone down kids again. So it is absolutely one of the factors that is helping us see growth in our traditional schools again.”

Courtesy: U.S. Coast Guard

For Miami-Dade superintendent, the issue is personal

District officials say they’re ready and willing to welcome this latest generation of immigrant families. For many, the issue is personal.

“I was one of these kids that started at Citrus Grove Elementary with no English whatsoever,” District Superintendent Jose Dotres told reporters.

Dotres was five years old when he came to Miami from Cuba. He went on to teach English to speakers of other languages in the same district where he first learned the language.

“I see myself in these students,” he said. “I see their parents as my parents so many years ago … but proud and confident that they’re entering a school district that knows how to support [them].”