Kids are picking up on post-election anxiety. Here’s how to help.

With the presidential election unsettled, kids (and parents) can use this time to learn coping skills, experts say.

Tampa Bay Times | by Sharon Kennedy Wynne | November 5, 2020

Two in three U.S. adults say this election has been a major source of worry, according to the October “Stress in America” survey conducted by the American Psychological Association. And with so many unknowns after the election, some fear the stress is spreading to the kids.

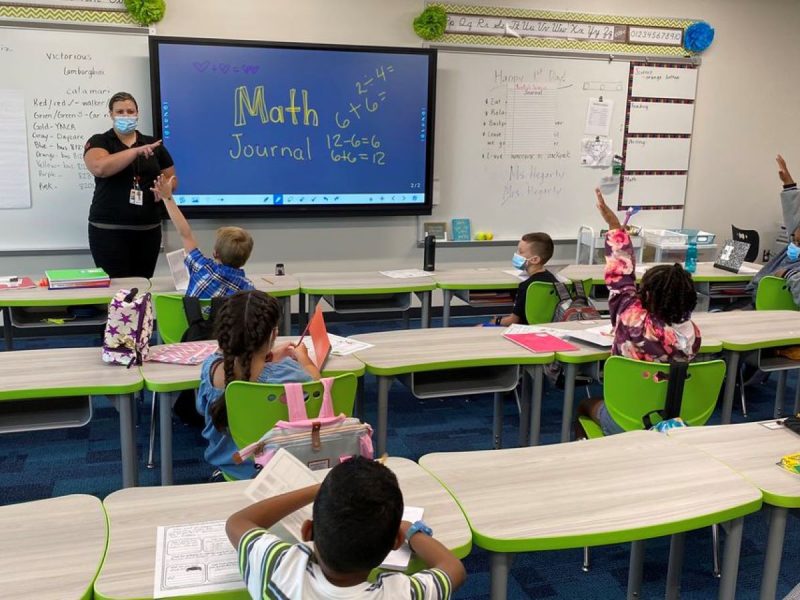

Schools have seen bullying and anxiety rise with the election season as kids took sides. And mental health professionals warn that parents should be on alert for signs of stress, such as irritability, changes in sleep or appetite or a decline in grades.

“Yesterday I was in a constant state of anxiety all day, not knowing and not being in control, it just makes me so nervous,” Tori Foltz, a 17-year-old senior at Seminole High, said of Election Day.

Even the day after, when a presidential victory was yet to be declared, there were moments of tension in the air on campus, she said. In the late afternoon, she overheard Trump-supporting students gasp as they saw red states turn blue on the electoral map.

Foltz worries things are “going to get worse because everyone has so much built-up anger and they have nowhere to put it.” She has seen friendships upturned by the election.

“One of my friends that we have a mutual friend with was posting that ‘If you don’t pick a side you are uneducated,’ and they started arguing and they ended up blocking each other,” Foltz said. “I would never want to ruin a friendship over something like that. We can have different political views and still be friends.”

Hillsborough County School Board member Karen Perez, who is also a clinical social worker, said she has witnessed conflicts pop up that, in her opinion, were when students were “bringing their parents viewpoints to school.” There have been instances of bullying, and she thinks kids are soaking up the anxiety they sense from adults around them.

“Children get their cues from us and how we feel so we don’t want to scare them,” Perez said. But she suggests it can be a life lesson on how we can face disappointment, learn to be gracious in victory or defeat, “and it can change the face of how we get along.”

Dr. Marissa Feldman, a pediatric psychologist in the Johns Hopkins All Children’s Institute for Brain Protection Sciences, works with children and families to teach them coping and behavioral skills.

“Parents might try to shield kids, but they still pick up on it,” Feldman said. “So give them an outlet and safe space to ask questions. It’s always great if you are feeling anxious, to label your own emotions and helps kids understand those feelings are normal and develop a language about what to do about it.”

Then after talking about your feelings, Feldman said, turn off the TV and screens, go for a walk, or do a family activity. For some people, she said, they can feel some semblance of control by taking actions like joining a civic or community event or cause.

That is what Foltz says has helped. So did Kieran Stenson, 17, a senior at Palm Harbor University High, who attends school online these days. Both teens have been involved for the last few years in the MediaWise Teen Fact-Checking Network run by the St. Petersburg-based Poynter Institute, the nonprofit journalism school and research institute that owns the Tampa Bay Times.

They have learned how to discern fact from fiction online and they post fact checks and media literacy tips on Instagram on what they found. The network of close to 30 teens nationwide (about 100 total since the program started in 2018 as part of the Google News Initiative) has drawn more than 33 million views to its content found on Instagram @mediawise and at poynter.org/mediawise.

Stenson credits what he’s learned as a way to make him feel more in control, that he’s not easily fooled by the wave of misinformation that has washed over social media this election season.

Perez said taking some action has been her suggestion, for students and her own grandchildren, on how to turn anxiety “into concrete things we could do now, how we can make the world better.”

“If the candidate you liked didn’t win, how can we make things better so it could turn out different next time?” said Perez, who joined the school board in 2018. “It can be reassuring to our children that they can have a plan for the future and that plan is positive they can make the world a better place the they want to be in.”

But that may not keep any of us, including kids, from endlessly checking Twitter and the news several times a day to find out if we know we have a president yet.

“I’m stressing. I’m stressing. I’m on my phone every 5 seconds checking on the results,” said Ja’Shanna Lyons, 16, a junior at Lakewood High School in St. Petersburg.

She had her journalism class roaring with laughter as she entered the class ranting “Can we get a winner? And they are like, ‘Stop the counting. Stop the counting.’ What? This makes me mad,” she said in a video one of her friends captured.

She turned her back in disgust and marched off as the class erupted in laughter.

Featured image: A poll worker assists Rachael Friedlander, of Washington, to vote with her sons, Shay Burke, 4, left, and Julian Burke, 6, right, at an early voting center at Ida B. Wells Middle School, Thursday, Oct. 29, 2020, in Washington. Mental health professionals warn that parents should be on alert for signs of stress as kids absorb the same anxiety as their parents. One way to combat that, they said, is to include them in civic activities so they feel like they are taking part. [ JACQUELYN MARTIN | AP ]