‘People are frightened.’ Florida’s book rules cause a chilling effect in Miami-Dade schools

Miami Herald | By Sommer Brugal | June 8, 2023

iPrep Academy in downtown Miami was established to close the digital and cultural divide and ensure every child had access to technology.

Founded by former Superintendent Alberto Carvalho, one thing that made it distinct was the absence of a physical library; everything was digital. And the model worked.

It wasn’t until the onset of this school year that a group of parents agreed it would be good for students, particularly young children, to have a space to gather and experience books away from another screen. By October, a group of parents, including Elizabeth Casal, had built shelves for the school’s new media center.

They named it Starbooks.

At the time, it was Casal’s understanding that around 500 books would be displayed; more importantly, she understood the books had been ordered. But as the final week of the 2022-23 school year wraps up, the shelves at Starbooks remain empty, she said.

District officials said the books were at the school, just not yet available because the media specialist and iPrep staff need to ensure the books align with the appropriate grade level — elementary, middle or high — before placing the books on the shelves. Moreover, the media specialist was just recently awarded full certification. Officials assured the delay was not another example of book restrictions or regulations stemming from new state laws.

For Casal, though, the empty bookshelves appear to be just that.

“What I’ve seen at our school is that there is an effort to have these books and to lift up diverse voices and have diverse people in the classrooms. I’ve seen that effort,” she told the Herald. “But I also see this force coming from the state that is making it harder for everyone trying to get these things done.

” Starbooks is scheduled to open for the 2023-24 school year.

The apparent misunderstanding — and delay in ensuring the books were available — between the parents and the district points to the ongoing confusion surrounding book restrictions in Florida. It also underscores how, in some instances, the new laws are causing a chilling effect and allow for what some say are the behind-the-scenes decisions being made regarding books.

‘FAR REACHING’ LAWS

Brooke Sussman, a parent of two in the district, including one at iPrep, was confused when she received a consent form for the Scholastic Book Fair last month. The consent form to attend the popup book store inside the school included a provision to hold the district harmless should their child return home with a book they didn’t approve of.

“My first thought was disappointment. Not for my child, but for this community,” Sussman said. For many families, a financial barrier for participation already exists, she said. “With the addition of a permission slip, I think some families will miss it and others will think maybe there is something I should be concerned about and choose not to sign it.”

She understands the fear many educators are experiencing amid new laws and debates around what is or isn’t age-appropriate. But the permission slip, she said, “illuminated how far reaching these movements to have content restricted” have gone.

District staff did not respond to a question regarding why the forms were being required toward the end of the semester. Previous fairs had already occurred this school year without requiring parental consent for participation, parents said. However, the forms were distributed because the list of books sent to each school is not always made available prior to the fair, staff said.

Nevertheless, the consent form “was kind of bringing political rhetoric in [the school] and making it real for the first time,” said Casal.

Teachers, too, are facing new protocols for determining what can or can’t be used in their classrooms — a move some argue is the result of misinformed decisions made by lawmakers.

Ramon Veunes, a teacher at Dr. Rolando Espinosa K-8 Center in Doral, said after the new laws went into place, he was told that any book outside of the district’s curriculum would require a more tedious approval process, regardless if a teacher already had it in class, such as a vocabulary book he’s used for years that he said correlated with state standards.

“We are professionals and we’re the most qualified in determining what to teach our students,” he said. When these laws are passed, teachers’ professional opinions are often not solicited, he said, and in some cases, this can “enable a single parent to affect what an entire school learns or doesn’t learn.”

Veunes said he will abide by the law, but argued it is “cumbersome and makes our job harder, [and] is wrongheaded.”

At George Washington Carver Elementary in Coral Gables, teachers recently were notified they’d have to catalog their classroom libraries to then be made public on the school’s website.

The email, obtained by the Herald, said the move is the result of a law passed last year — HB 1467 — that requires more transparency for the public when selecting instructional materials, including library and reading materials. (Florida teachers unions and other groups sued the state education department, arguing officials overstepped the intent of the new law by including classroom libraries.)

The email said the effort was a “fantastic time” to go through classroom libraries and “weed or remove any damaged or old books, as well as audit for ‘age appropriateness.’”

The district did not respond to questions inquiring whether teachers were given a rubric or a definition to determine what was considered age appropriate.

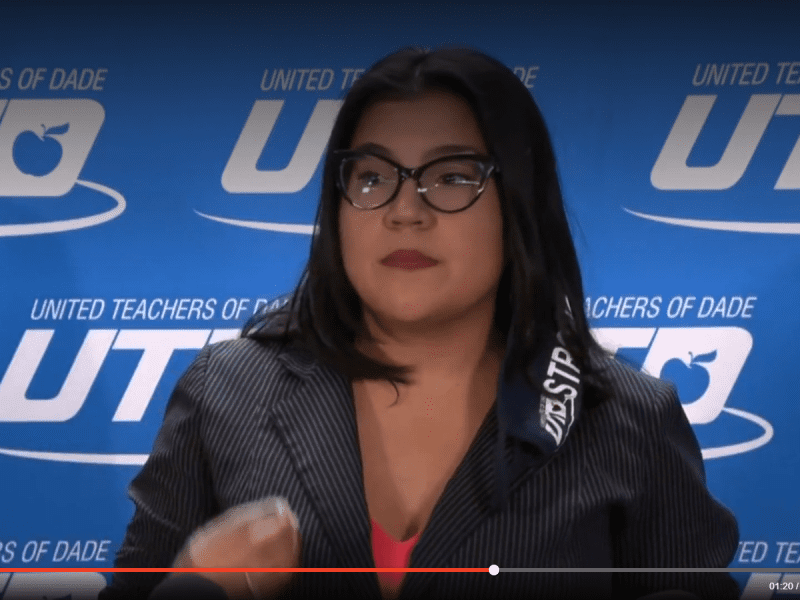

Karla Hernandez-Mats, president of United Teachers of Dade, spoke at an event on June 6, 2023 to raise awareness about censorship and to offer a stark rebuttal to the recent decision to restrict four titles from elementary students in one Miami-Dade County school. Sommer Brugal

Karla Hernandez-Mats, president of United Teachers of Dade, told the Herald she instructed her members not to comply with the request. The process, she said, highlights what she argues is an attack on public education and underscores the confusion many teachers are facing amid vaguely-written laws.

If a teacher is unsure if a title is acceptable, many may opt to remove it from their shelves to avoid any trouble later on, she said.

“That’s the state of education,” Marvin Dunn, historian and professor emeritus at Florida International University, told the Herald late last month. “People are frightened. They aren’t sure and are being overly cautious” about the materials they use, which has a chilling effect on what is being taught, he said.

ONE PARENT’S COMPLAINT

The act of removing a book from school shelves — and the outrage about how it was done — isn’t new for Miami-Dade Public Schools.

In 2006, the father of a 10-year-old student at Marjory Stoneman Douglas Elementary complained a book his daughter brought home painted an inaccurate depiction of life in Cuba. The school board voted to remove the book, “Vamos a Cuba,” from school shelves, despite two academic advisory committees at the time suggesting leaving it. The ACLU filed a lawsuit claiming the board’s decision violated the Constitution, according to a 2009 Herald story.

The issue went up to the Supreme Court, but was denied a hearing. The book remained off the shelves, following the ruling of an 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta that said the School Board had not breached the First Amendment and supported its authority to set educational standards in Miami-Dade.

Nearly 20 years later, the district is again in the spotlight after just one parent complained about five titles.

Daily Salinas, a parent of two at Bob Graham Education Center, a K-8 school in Miami Lakes, claimed the titles included what she said were references to critical race theory, “indirect hate messages,” gender ideology and indoctrination. Four of them, including Amanda Gorman’s poem, “The Hill We Climb,” which she recited at President Joe Biden’s inauguration, were moved to the middle school shelves.

Salinas has denied any affiliation with Moms for Liberty, a self-proclaimed parents-rights organization that was recently labeled an extremist group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, despite appearing in multiple photos with local chapter leadership. The group is behind many book removal efforts nationally, according to an analysis by the Washington Post. A representative from the national chapter said Salinas was not affiliated with the group, but did not respond to a question about the perceived relationship between the parent and local leadership.

The district has maintained the titles were not banned but simply moved. Reading and education advocates, however, say it’s still a restriction to younger students. (Dunn and Hernandez-Mats, along with other prominent Miami educators and literary and civil rights organizations, spoke on Tuesday at a book giveaway and celebration to push back on the decision made at Bob Graham.)

For Stephen Hunter Johnson, a district parent, Miami lawyer and member of the Miami-Dade County’s Black Affairs Advisory Board, the ease with which one parent’s challenge can result in less access for all students is “incredibly concerning and alarming.”

“What was done here was nothing short of a travesty,” he told the Herald after the restrictions were made public. “The school district is dead wrong on this, for allowing this ad-hoc review process [and] doing these things under the cover of darkness.”

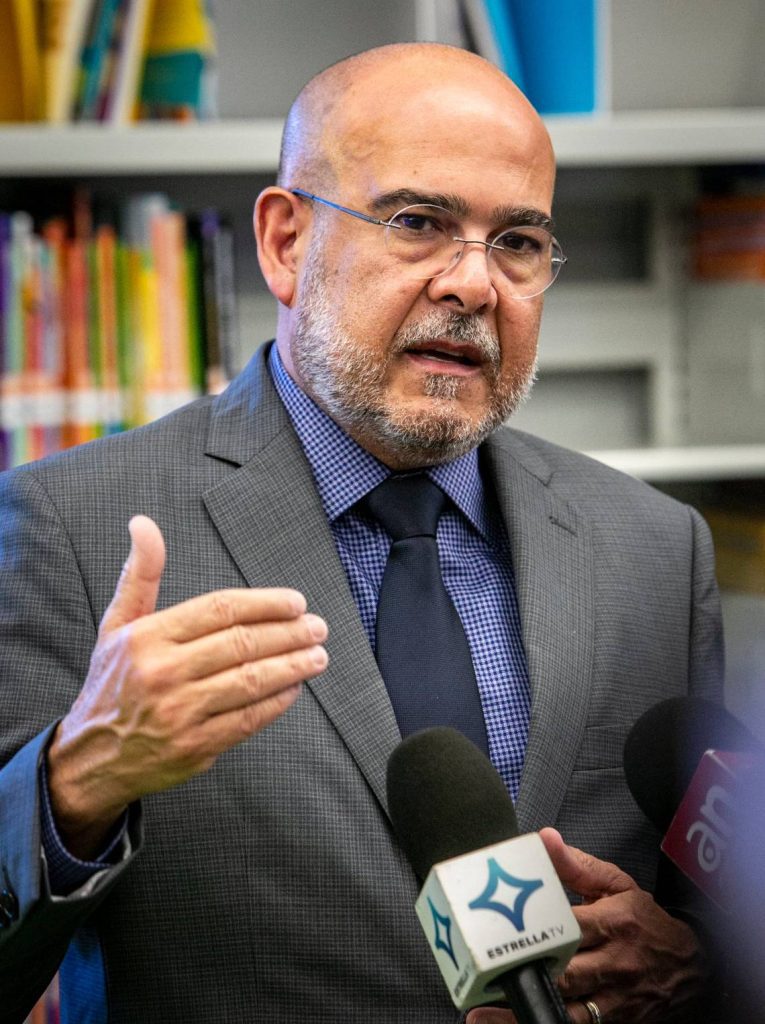

Superintendent José Dotres, pictured on August 17, 2022, the first day of the 2022-23 school year, said the review committee’s decision followed district policy. Jose A. Iglesias jiglesias@elnuevoherald.com

At a news conference Wednesday, Superintendent Jose Dotres defended the committee’s actions, saying it “followed proper procedures” but added “there’s always room for improvement.” Perhaps officials should raise more awareness about existing policies, he said.

Nevertheless, Johnson argued, if one parent has a right to complain, other parents should have the right to push back. The purpose and effect of laws like this is to chill what otherwise what would be normal expression, he said; it’s easier to come up with these absurd solutions than it is to push back.

Stephana Ferrell, director of research and insight at Florida Freedom to Read Project, agreed. The organization, which obtained records of the decision at Bob Graham and shared them with the Herald, is arguing for more transparency surrounding the initial school-level review process.

In many districts, including Miami-Dade schools, a school-level review committee is the first and sometimes only step in determining whether a book should remain on shelves; policies don’t require complaints to be made public. As a result, those school-level discussions are often kept quiet and most of the discussions go “under the radar” unless a decision is appealed, Ferrell said.

“We don’t want to see the school-level step disappear,” she said. Instead, what organizations like hers are arguing for “is that every parent knows when a book is challenged.”