School librarians from across the nation speak about mounting pressures

WUSF | By Nancy Guan | October 24, 2023

The American Association of School Librarians held its biannual conference in Tampa. Some painted a stark picture of the profession in a polarized political climate.

When Cynthia Stogdill recounted the past year working as a high school librarian in Nebraska, she became emotional.

“I was not okay at the end of the year,” said Stogdill, “I didn’t know if I could keep doing it. But the thing that kept coming back to me was our students. And I had to say, if I don’t do it, who will?”

For Stogdill and many other school librarians across the nation, their role has become increasingly politicized. State laws restricting what materials should be in K-12 schools and mounting scrutiny from parents have led to a record number of book challenges.

The American Association of School Librarians Conference held at the Tampa Convention Center from Oct. 19 to 21 addressed these issues school librarians are facing today.

Speakers, including Stogdill, talked about how to preserve intellectual freedom amid a surge of censorship attempts from parental rights groups and community members.

“There’s several school librarians that I’ve spoken with, who have decided to take jobs in other areas of education or have left education entirely, or they have been removed from the position that they were in and put into a different teaching area.”

AASL President Courtney Pentland

“Students need an advocate in the pursuit of equitable access to information and resources. And often their school library is their home library and their only free library,” said Stogdill. “Our students’ experiences and lives should be reflected in our collection.”

But as data from the national advocacy group PEN America shows, about 30% of books banned include characters of color and themes of race and racism, or represent LGBTQ+ identities.

Florida sets book ban pace

Laws that restrict teachings ontopics like race, gender, American history and LGBTQ+ identitieshave spurred these efforts, PEN America writes.

Florida led the nation with 1,400 attempts to remove or restrict books in public school libraries last year.

The growing movement to limit access to books and library services is taking a toll on school librarians, said AASL President Courtney Pentland.

“There’s several school librarians that I’ve spoken with, who have decided to take jobs in other areas of education or have left education entirely, or they have been removed from the position that they were in and put into a different teaching area,” said Pentland.

She noted that this is not the first wave of book bans the U.S. has experienced, but the severity is apparent.

“There are people who are facing death threats, who are being doxxed with their personal home addresses and phone numbers,” Pentland explained. “There are people who are being threatened with physical harm, people who get yelled at and called names, and that is very taxing and exhausting mentally.”

In some states, obscenity laws that allow for the prosecution of librarians, educators, college and university faculty, and museum professionals have been passed or introduced. Penalties can include tens of thousands of dollars in fines and jail time.

“I don’t think that any of this is coming out of district leadership trying to be like, ‘kids shouldn’t have books.’ It’s coming out of fear. They don’t want their teachers and media specialists to be in a lawsuit situation.”

Kathleen Daniels, president of Florida Association for Media in Education

“Gather your network, your circle of people you can trust, and be very mindful of your school communication because request for information or Freedom of Information Act records — they will request nonstop,” said Stogdill.

The effect on their mental health

Jennifer Dillon, a Hillsborough County school librarian, who attended Stogdill’s lecture, said the testimonies she’s heard from other educators have been eye-opening.

“Librarians are saying things like after having been through a series of challenges or a season of challenges, they’re saying I’m not okay,” said Dillon. “It’s really affecting the mental well-being of people in libraries who are simply trying to do right by students … and I think it’s really coming to a point.”

Dillon said workloads have increased significantly. Not only do librarians, sometimes referred to as media specialists, have to catalogue the collection in their own libraries, but the law has expanded to include the classroom libraries of school teachers too.

This has put enormous strain on school librarians, who are often the only librarian on the job at their school, said Kathleen Daniels, president of Florida Association for Media in Education.

“Now each media specialist is having to comb through every single book that any teacher wants to have in their classroom,” said Daniels. “In some middle grade or high school, it might be a couple of hundred books, some individual teachers have over a thousand books … that’s a whole other job.”

Some school teachers have opted to clear their bookshelves out of fear, said Daniels.

School boards and educators across the state have called on the Florida Department of Education for more guidance on how to implement these new statutes and criticized the language in the legislation for being vague.

Operating without clear direction

Tina Hackey, a librarian from Volusia County, said trying to implement book challenge policies without clear direction on state laws has been like “trying to build the plane while you’re flying.”

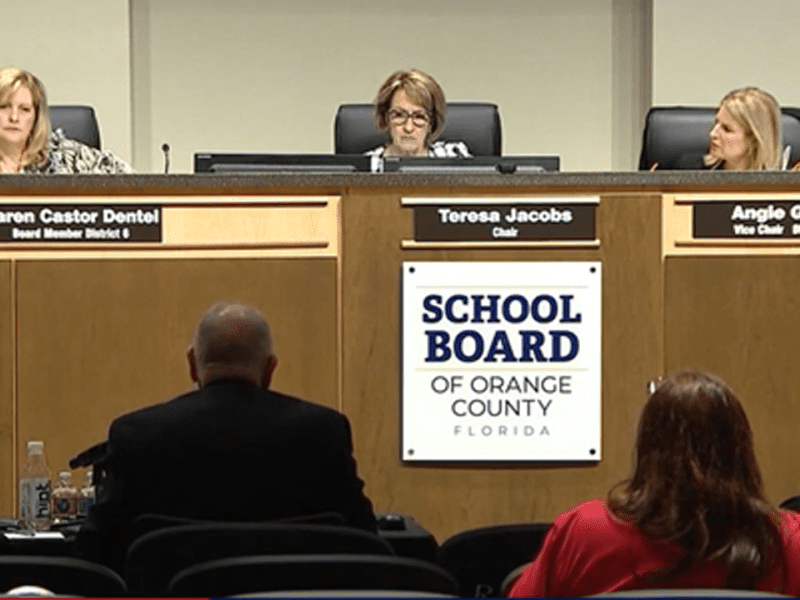

Some school boards have circumvented their own policies, by pulling books off of shelves after passages were read aloud during public meetings, instead of requiring an objection form be submitted for each book being challenged.

In some cases, Hackey said, parents groups have begun passing out objection forms at school board meetings.

“They read the dirtiest parts of the books and give out challenge forms at the meeting so that it could be filled out right there,” said Hackey.

According to state law HB1069, books must be pulled within five days of when an objection is filed, which Hackey calls a “guilty before innocent” mindset.

Organized campaigns from groups like Florida-born Moms For Liberty are driving the challenges that sometimes generate long lists of books to be reviewed.

“Most of us have to now do triple, quadruple the work to make sure that the books in our collection have the right number of reviews,” said Daniels. “I don’t think that any of this is coming out of district leadership trying to be like, ‘kids shouldn’t have books.’ It’s coming out of fear. They don’t want their teachers and media specialists to be in a lawsuit situation.”

But Pentland, president of AASL, said advocacy for school librarians are ramping up as well.

Organizations like the AASL, the American Library Association, FAME, PEN America and the Texas-based FReadom Fighters have launched resources and studies to aid librarians and educators.

“There’s always an element of advocacy in our work,” said Pentland. “We’ve had to hustle for things for a long time [but] this is a different level of advocacy, a different branch that hasn’t had to happen for a while. It’s definitely a different tone.”