Why Florida teachers are so woefully underpaid

Most U.S. teachers suffer from a “teacher wage penalty,” but Florida ranks 49th in the nation in average salaries.

Fast Company | By Lilian Manansala | July 15, 2021

When Jared Smith moved from Orlando to Tampa five years ago, he found a one-bedroom apartment he couldn’t afford on his salary within a mile of his job, so he sold his pick-up truck to make first and last month’s rent and started walking to work.

When his colleague MaryAnn Robertson started working in Vermont in 1974, her salary was $6,800. Along with her husband’s bartending income of $12,000, they were able to purchase a three-bedroom home that included a duck pond in the back. The bank even encouraged them to buy a more expensive home.

Jared, 32, and MaryAnn, 69, are generations apart, yet they are both tied to a system that asks more from them than what they are compensated for. They work in a state that ranks 49th in the nation in average salaries for their occupation, while week after week, they log in extra hours of unpaid labor to meet the demands of one of the most important jobs in the world.

They both teach high school in Florida.

The fact that K-12 educators in America are underpaid is well known. But given the renewed focus on the role of teachers during the pandemic and Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’ recent acknowledgment that salary increases were long overdue, the state stands out for the unique factors and singular forces that have kept teacher salaries so low for so long.

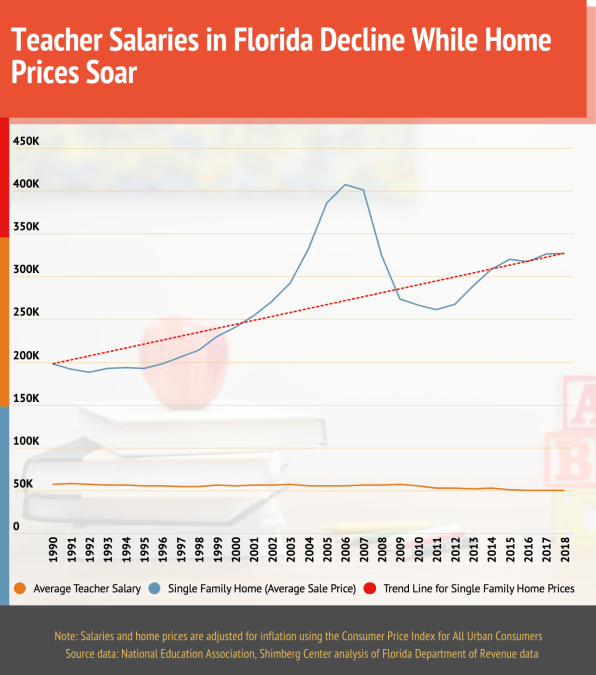

Over the last two decades, Florida teachers pay has decreased 12.5% when adjusted for inflation. In a 2020 study by the National Employment Law Project, teachers experienced the greatest decline in wages out of all the occupations included in their report—a whopping 18.6% reduction in median hourly wage from 2009 to 2018.

Teacher turnover is high largely because salaries are so low and pay raises so paltry. Average pay for teachers in Florida decreased, ranking the state 47th in 2019 to 49th in 2020. Though DeSantis is set to increase the starting pay for teachers to $47,500, there is criticism that veteran teachers are being overlooked. Salaries for Florida teachers in their mid to late careers hardly reflect their years of experience. As a relatively new teacher with five years’ experience, Jared sees a gross pay of $44,000. But after 34 years of teaching, 16 of them in Florida, MaryAnn earns only about 50% more than Jared: $67,000.

An outspoken, creative, out-of-the-box thinker, Jared has an intense energy—once a chef, he learned to be detail-oriented and a perfectionistic—but he tones that down when he’s teaching his students. He also suffers from anxiety—there is always “a lot more going on inside”—and hopes that makes him more relatable to the kids around whom he feels more like himself.

MaryAnn has delicate features, bright eyes and a wry sense of humor. She tells stories from her days as a journalist—as a theater critic, features writer, and education reporter. She expounds on her love of theater and musicals, and the walls of her classrooms are filled with Broadway show posters. Like many of their colleagues, Jared admires MaryAnn, calling her a “force of nature” and a “paragon” of what he hopes to become as a teacher.

They both teach at George S. Middleton High School in Hillsborough County, Fla. They are both English teachers with master’s degrees. He is an instructor for Exceptional Student Education (ESE); she primarily teaches Advanced Placement (AP) students. Their moms were also both teachers. But their respective mother’s experiences could not have been more different.

Jared’s mother, Marcia Barager, taught in 2009, but the pay was so low she stuck it out for only three years; she was trying to get away from Jared’s emotionally abusive father and establish financial independence.

MaryAnn, who has a calm, soothing, yet professional voice, chuckled when asked to compare her financial well-being as a teacher to what her mother experienced in a career that also spanned decades. Her mother, Marion, taught from the 1940s to the 1970s and was the breadwinner of the family, earning more than her husband, who after a significant on-the-job back injury, sold real estate and ran a local bed-and-breakfast from the family home. A teaching career in Massachusetts not only enabled the family to own property, go on vacations and have a secure retirement—when MaryAnn’s father fell ill and was in the I.C.U. for 18 days, the health insurance coverage provided by the then-retired Marion’s job fully paid for all the expenses, with zero out-of-pocket costs.

When MaryAnn had her two children in 1978 and 1986, her teacher’s health insurance in Vermont covered every penny. She also had six weeks’ paid maternity leave that didn’t come out of her sick leave fund. MaryAnn moved to Florida to help take care of her parents in 2004 and has lived in the state ever since.

Nowadays, the health insurance package offered to Florida teachers is so barebones that employees must add options to meet basic needs. MaryAnn knows co-workers with children who can’t afford the family plan. If new mothers haven’t accrued enough sick leave, they take their maternity leave without pay.

Throughout the state, as well as the country, school districts have sought to shift health care costs to the employee. “So teachers are paying for their dependents’ coverage and part of their own—which means you literally have families who pay well above $1,000 a month for health insurance,” says Andrew Spar, president of the Florida Education Association. “And of course, that comes out of their very low wages.”

According to a 2020 study published by the RAND Corporation, workers like MaryAnn in the 75th income percentile would be earning 35% more if salaries matched real per capita GDP growth of 118% from 1975 to 2018. MaryAnn’s $67,000 would actually be closer to $100,000. Moreover, teachers in the U.S. are paid far less than people in other jobs with the same level of education.

In 2017, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development found that out of all the OECD countries, the U.S. had the largest salary gap between teachers and other workers with comparable training. The gap between educator salaries and those with comparable education in the U.S., referred to as the “teacher wage penalty,” has grown since the 1990s, from 1.8% in 1994 to 2017, when teachers made a record 18.7% less than their counterparts.

The idea that teachers’ pay is low because they work shorter hours, with classes ending by mid-afternoon, and get to enjoy an annual three-month vacation is far from reality. MaryAnn teaches eight hours a day, then works an additional three hours every day to prep and grade, plus more on weekends. But she’s paid only for 40 hours per week.

Like many teachers throughout the country, MaryAnn and Jared moonlight or work additional jobs to make extra money to pay their bills. MaryAnn also usually teaches at least four courses per semester at Hillsborough Community College throughout the year and in the summer has worked as an adjunct professor at the University of South Florida. Jared says he struggles to make ends meet and lives “1 to 1” from paycheck to bills. The only disposable income he makes is from his side hustles, photography and videography.

While Florida is at the bottom of the country for salaries for experienced teachers, its starting salaries are middle of the pack. Before DeSantis’ increase, Florida ranked 30th in the nation for average starting salary at $38,724 for the 2019-2020 academic year, according to the National Education Association (NEA). But what did the actual increases and bonuses look like for these teachers? Newer teachers got a $350 raise per paycheck, others only $37, and some veteran teachers—nothing. MaryAnn says she was among the teachers at the top of the pay scale who received a one-time bonus of $250 at the end of the pandemic year “for just hanging in there. It was a joke.”

The cost of living in Florida is not as low as one might assume from the salaries, says MaryAnn. “We expect teachers to be saints,” said Richard Ingersoll, a professor of education and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, “that teaching is a labor of love, and somehow we justify that saints don’t need to get paid, saints don’t have mortgages.”

Education experts primarily blame state lawmakers for teacher wage stagnation in Florida, since they determine how much of the revenue gained by property taxes goes to schools.

The U.S. is one of the few developed countries that leaves public school education under the control of states and school districts and that ties its school funding to local property values. The more affluent a neighborhood, the higher the property taxes, and the more can be allocated to public education budgets. And Hillsborough’s property taxes don’t yield, for example, what Miami-Dade’s waterfront real estate does, says Robert Kriete, president of the Hillsborough Classroom Teachers Association.

School districts are at the mercy of state legislators and their governors. While lawmakers don’t determine millage—the calculation of property tax liability—they are the ones who can approve increases, which many are reluctant to do in a state that prides itself on its reputation for low taxes and has been busy cutting taxes for the wealthy and corporations, further decreasing potential funds for school budgets.

Although the Biden administration is hoping to curtail teacher shortages and support teacher training in the American Families Plan, it doesn’t address low teacher pay. Save for “No Child Left Behind,” which focused on test-based accountability, federal involvement in education is constrained by the Constitution, which makes no mention of education and therefore assigns responsibility for schools to the states. (The federal government has, however, used the carrot of funding and the stick of lawsuits to promote equal protection for students against discrimination, most prominently in desegregation battles).

Decentralization of the education sector is one of the reasons why states vary so widely when it comes to teachers’ pay and student outcomes. Annual state spending per student was $24,040 per student in New York and $9,346 in Florida. Jared says that his classroom has a television set older than his high-school students.

In March, about a hundred Hillsborough teachers were laid off due to budgetary problems. According to MaryAnn, they were “let go very unceremoniously with anonymous emails that weren’t even personally addressed.”

Some state lawmakers actively oppose funding for public schools, says Kriete, who notes that several of them have pulled him aside, telling him off the record that they don’t believe the Florida government should pay for free and high-quality public education. “They don’t want to pay for teachers’ retirements. They don’t want to offend anybody in the education field, but they would just like [education] to be completely privatized here in the state of Florida.”

Though teacher unions in the state have played a powerful role in convincing DeSantis to support pay increases, the fact that Florida is a right-to-work state weakens the unions financially. Research shows that right-to-work laws tend to hamper both union and non-union workers’ ability to secure better wages as well as employee protections and job benefits.

Middleton, where Jared and Maryann teach, is one of over 250 schools in the Hillsborough County School District, the eighth largest in the nation with over 200,000 K-12 students. It’s a district with lots of movement—both teachers and students transfer constantly. The dynamic perpetuates a vicious cycle: Low salaries don’t attract teachers who stay in the job; poor retention and high turnover negatively impact student performance, which lowers a teacher’s performance evaluation, which results in no raises, which depresses pay. And even if a teacher’s evaluation is high, the raises are not nearly enough to keep them on the job.

The pandemic generated a greater social and cultural appreciation for teachers because parents were suddenly forced to juggle remote work and homebound schooling. However, that support hasn’t been evident at the legislative level: DeSantis has opposed teacher unions’ demands for across-the-board pay raises, Florida’s House and Senate have pushed back on Biden’s American Rescue Plan that provided $1,000 federal stimulus bonuses for teachers, and state lawmakers have long promoted merit pay for teachers, though it has proven to be an ineffective tool for increasing student performance.

Overall, the driving force has been an overemphasis on budget austerity, even when it comes to essentials like public education, going back to the recession when then-Gov. Rick Scott cut $1 billion in state education funding.

“What I find odd is that there seems to be a disconnect between what the public sees and believes in,” said Kriete. “We do know that our community supports our teachers, and our communities believe in public education. But the legislature doesn’t seem to want to show teachers respect that comes with the dollars—to give them a better wage for the important, very difficult job that they’re doing.”

A leisurely summer is unlikely for MaryAnn and Jared, only two of the millions of teachers who deserve a break from an especially difficult year. They can hardly afford one. MaryAnn is teaching three classes at the community college this semester, and spent a week in June reading 700 essays for the AP English exams. Jared is helping build a menu and kitchen staff at a local restaurant, hoping to get his skills back in shape before he starts a culinary arts program at the school.

“When I was a cook I had no problem with free labor,” said Jared. “I would come into the $6 million kitchen and work an hour early and leave an hour late. And I had no problem with it, because I was learning something every day. But when it comes to teaching, you’re not learning something every day, because you’re coming back to the same exact set of issues every day. And nothing is changing. The figureheads, the bureaucrats change, but the situation stays exactly the same. It’s you and your kids, and you do the best you can.”