Florida school districts tell parents: Sign this form if your child prefers another name

Herald Tribune | By Finch Walker | August 15, 2023

All students who go by an alternative name to their legal name — even those using basic nicknames — must get parental approval.

Samantha Kervin hasn’t had to think much about what name she goes by in the past. In class and to her friends, she’s “Samantha” or “Sam.” It’s never been a big deal.

But this year, with a new rule put in place by the Florida Board of Education that requires a parent’s signature if a student wants to go by an alternative to their legal name, her nickname is causing more of a hassle.

“It kind of just annoyed me that people wouldn’t be able to be called by what they want to be called because of a form,” the Brevard ninth-grader said. “That seems counterintuitive.”

In districts across Florida — including Brevard, Orange, Seminole, Sarasota, Leon County and more — administrators are in the process of getting the form out to parents as the new school year kicks off.

“It should be available to parents beginning this week,” said Russell Bruhn, spokesperson for Brevard Public Schools, adding that the form is available to individual schools to provide and on the district’s website.

The new requirement comes after a July meeting of the Florida Board of Education, where the board laid out guidelines for school districts regarding how to follow recently passed legislation. It was there that they passed multiple rules affecting LGBTQ students, including a requirement for districts to have parents sign a form before their child could go by another name, though no law specifically mentions anything about whether or not a child must use their legal name.

At the meeting, Matthew Woodside, a Brevard teacher of 17 years who has been outspoken against local LGBTQ issues, spoke in favor of the rule. He said in the past, he has used nicknames for his students, but the amendment was necessary because the number of transgender students has “skyrocketed” recently.

“Many students are attempting (to go by a different name) without the knowledge of their parents, and many schools are complicit in this scheme, keeping this information from these parents, undermining the God-given rights of the parents,” he said.

“When something as sensitive as a student wanting to be called by a name of the opposite sex occurs, we must recognize that these students are minors. They are minors, and their desire for autonomy and secrecy will never trump the rights of parents to raise their child with full knowledge of who they project to be at school.”

Drew Kloes, a Brevard 12th-grader, disagrees with the idea that the rule protects children or parental rights. The 17-year-old considers himself lucky — he’s been out as transgender for about four years, and his parents are accepting. But the same isn’t true for everyone.

“(Florida is) trying to make it look like it’s protecting a certain group, but in reality, it is targeting minorities, including transgender people,” he said. “I know so many people who wouldn’t be able to do that and ask their parents to sign that form.”

While Drew said his teachers are respectful of using his chosen name, he said he and two other trans students were singled out by a teacher at his school and told they must get the form filled out by their parents.

“I just felt annoyed, and kind of really upset,” he said. “I felt like that was extremely unfair.”

About 150 people gathered at Eau Gallie Square on March 31 to celebrate National Transgender Day of Visibility. MALCOLM DENEMARK, FLORIDDA TODAY

But it’s not just trans students who are impacted: Anyone who goes by a nickname will have to fill out a form and turn it into their district, save for in Leon County, whose website notes that nicknames do not require a form.

Samantha, who said the form was discussed by all of her teachers on the first day of class, feels that the board’s rule has a broad impact on everyone.

“For the people that created and accepted this, (they) aren’t thinking of the broader consequences of said actions,” she said. “In my eyes, their view is one-sided, where all they see is what they want to see. They do not see the broader impact that it has on everybody, only (the impact) they want it to have on the certain people they attack.”

Why the rule was adopted wasn’t clear Monday. While HB 1069 prohibits districts from “imposing or enforcing” personnel or students to be referred to by pronouns that don’t correspond with their sex assigned at birth, the law doesn’t reference the usage of preferred names. The amendment posted to the board’s July 19 meeting agenda also doesn’t reference any law as a reason for the change, instead simply saying the purpose of the amendment was to “strengthen the rights of parents and safeguard their child’s educational record to ensure the use of the child’s legal name in school.” It adds that a local rule adopted by each school district around Florida will “ensure full transparency to enhance the student’s record and protect parental rights.”

Starting Wednesday, Brevard Public Schools will send out a series of messages reminding families to update their child’s nickname via the new forms. Bruhn said there will be three messages and that the goal is to have all names updated by the end of September.

The district referenced the board’s decision as the reason for the creation of the form, but went on to quote a Florida statute as the reason why teachers and other staff may not use a student’s preferred pronouns.

“It shall be the policy of every public K-12 educational institution that is provided or authorized by the Constitution and laws of Florida that a person’s sex is an immutable biological trait and that it is false to ascribe to a person a pronoun that does not correspond to such person’s sex,” the letter said, quoting Florida statute.

That statute also states that a student may not be asked by an employee of a public K-12 school to provide their “preferred personal title,” though Brevard did not reference that section of the statute.

In Leon County, the district blamed the change on HB 1557, dubbed the Parental Rights in Education by Gov. Ron DeSantis and the “Don’t Say Gay” law by critics.

Alternatively, in Sarasota County, the district referenced HB 241, the Parents’ Bill of Rights. The law was passed in 2021, and HB 1557 later drew from it.

“This rule, aligned with Florida’s Parents’ Bill of Rights, allows parents to specify alternative names that school personnel may use when referring to your child at school,” Sarasota Schools Superintendent Terry Connor wrote in an email to the district.

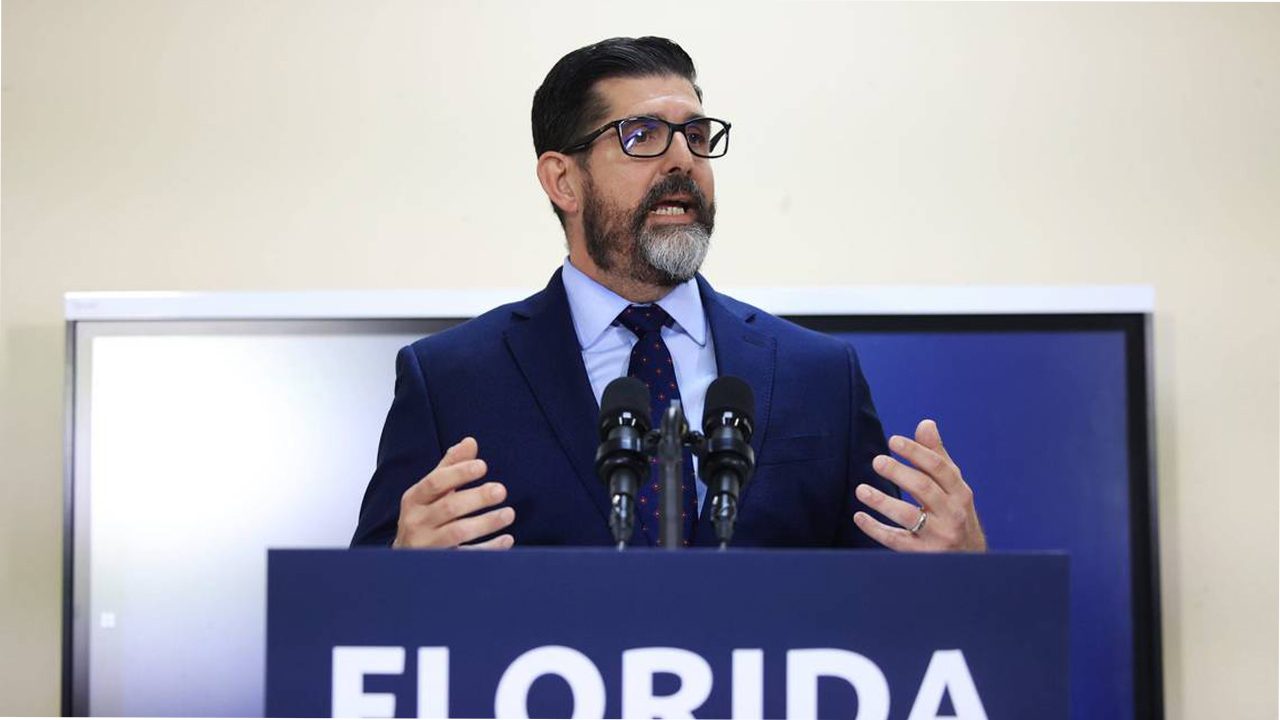

Emmy Kenney speaks at a rally to oppose the “Don’t Say Gay” bill (HB 1557) and other proposed legislation in West Palm Beach, Florida on March 1, 2022. Greg Lovett, The Palm Beach Post

Brandon Wolf, press secretary for Equality Florida, decried the rule, calling it part of DeSantis’ “war on academic freedom.”

“On top of navigating which classes are under siege, which books are being censored, which history lessons are being whitewashed and which bathroom their child will be forced into, parents are now having to complete paperwork to ensure their child’s name is being respected,” Wolf said in a statement to FLORIDA TODAY. “Florida’s families deserve better than a state government determined to make everything harder for them. And school districts deserve better than this Governor’s anti-freedom agenda of chaos and confusion.”

Drew said the new rule, on top of other anti-trans legislation, makes him feel like Florida is no longer safe for him.

“It’s just sickening, and it makes me feel unsafe in my home state,” he said. “It just makes me want to leave, and the only reason that I’m still here is because I’m still only 17, and I won’t be able to move until after I graduate, because I don’t want to move schools right as soon as I turn 18.”

For Samantha, the requirement sparks frustration. Though it’s an extra step she’s not used to taking, her parents are willing to sign the form. But she shares Drew’s frustration, knowing that that isn’t the case for some of her transgender friends who don’t have supportive parents.

“It’s upsetting because I can’t do anything,” she said. “I feel powerless in that regard. The only thing I can do is make people more aware of what’s going on.”